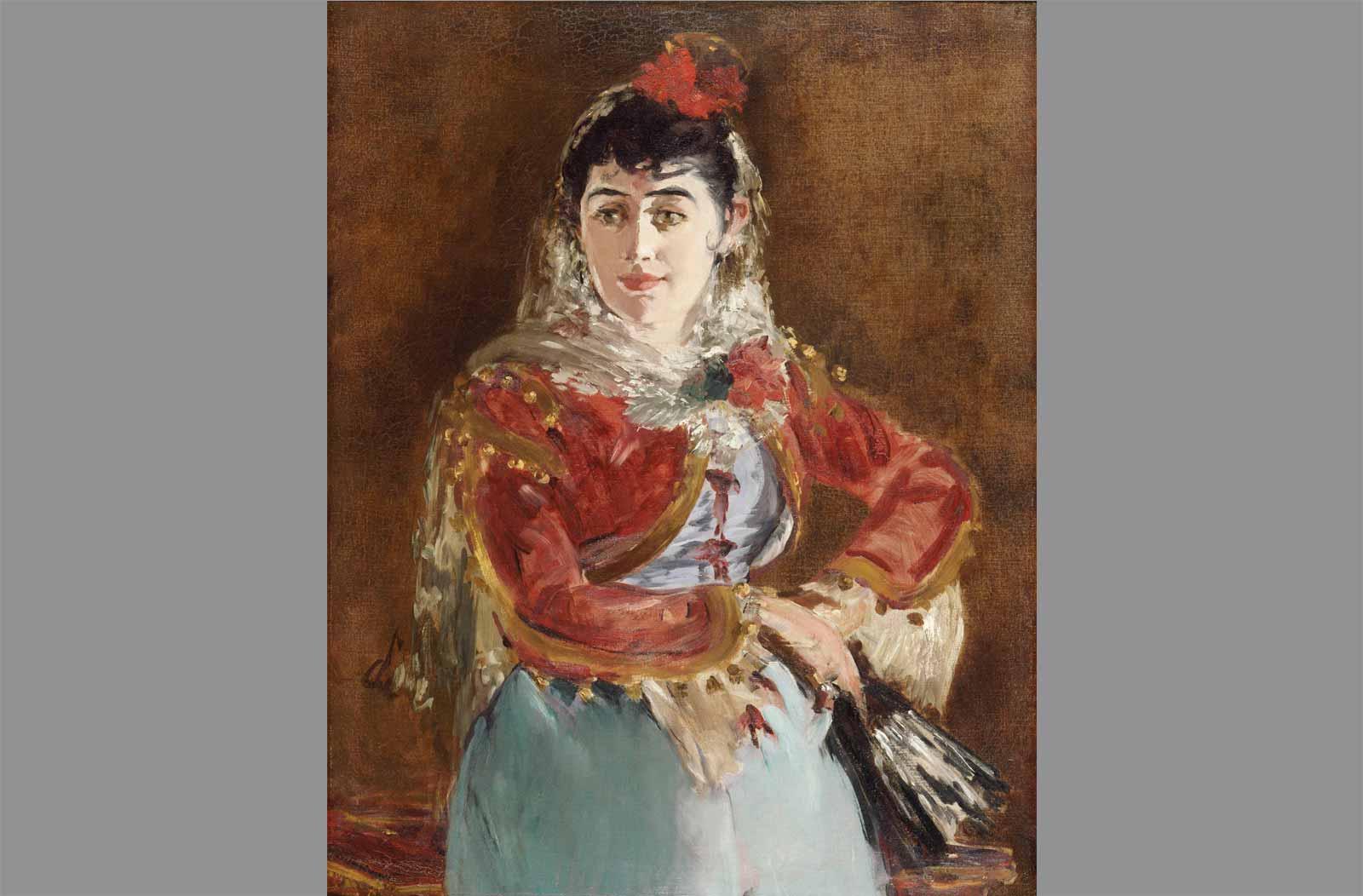

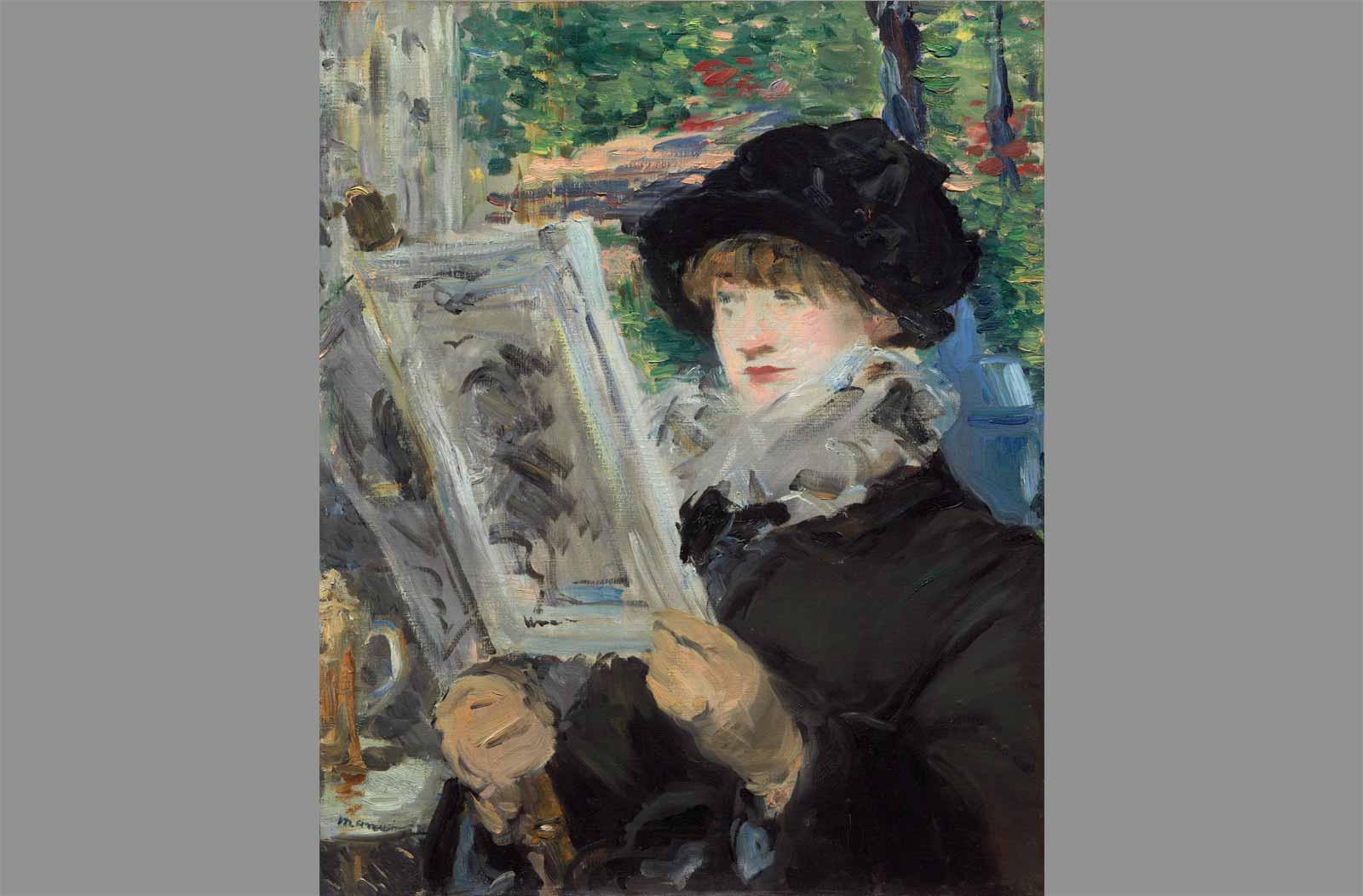

Eduoard Manet’s death was tragic for many reasons. The French painter’s life was cut short by complications of syphilis, and he passed away at the age of fifty-one on April 30, 1883, after many painful months. Despite his limited mobility as his health declined, he continued to paint in preparation for that year’s Paris Salon—which opened just days after he died. In his later years, he had also embraced a different mode of painting that critics largely dismissed for being too frivolous: he constructed portraits of fashionable women in pastels and pretty still lifes of flowers. They were major departures from his grand, large-scale masterpieces like Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe and Olympia.

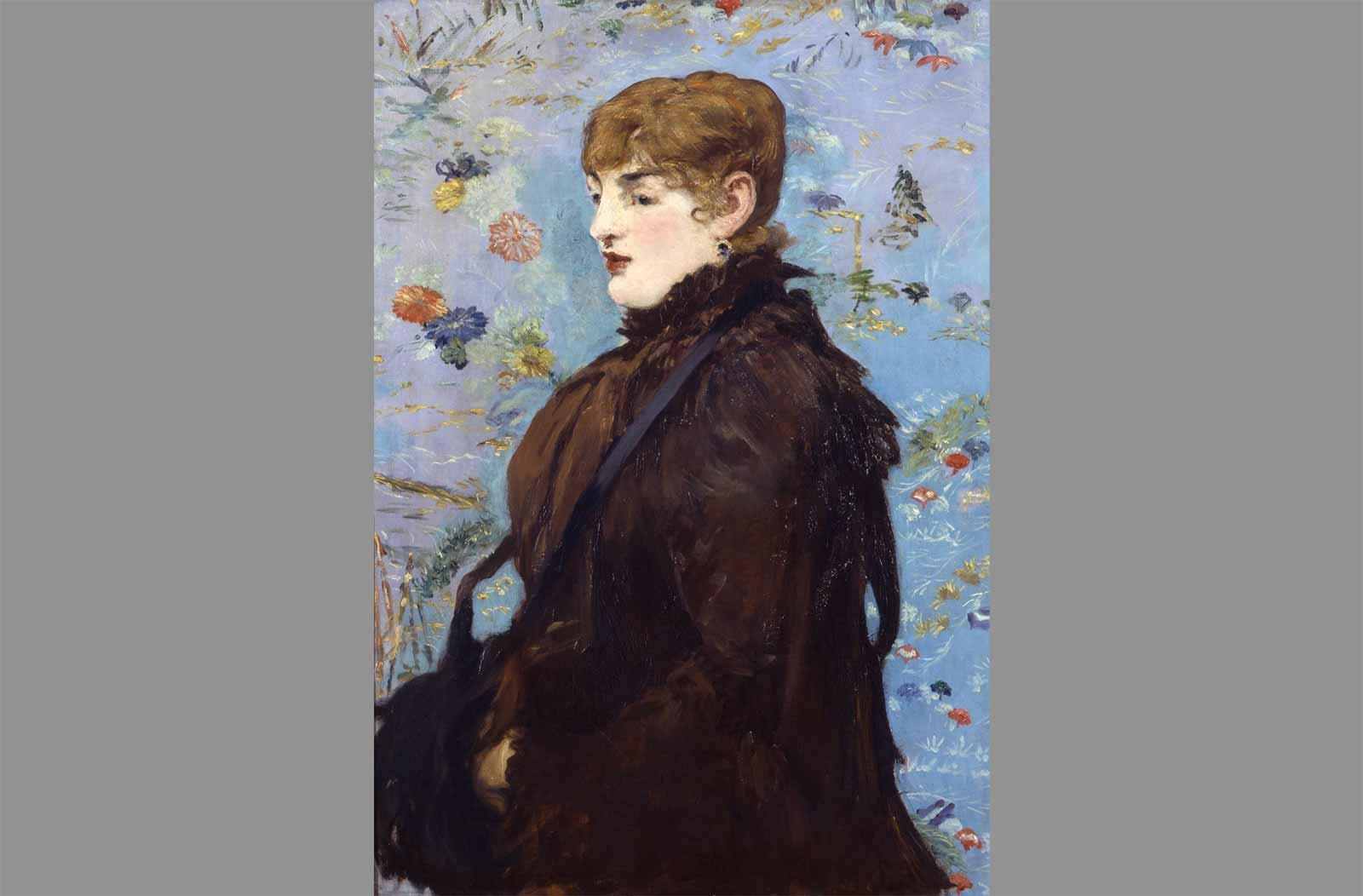

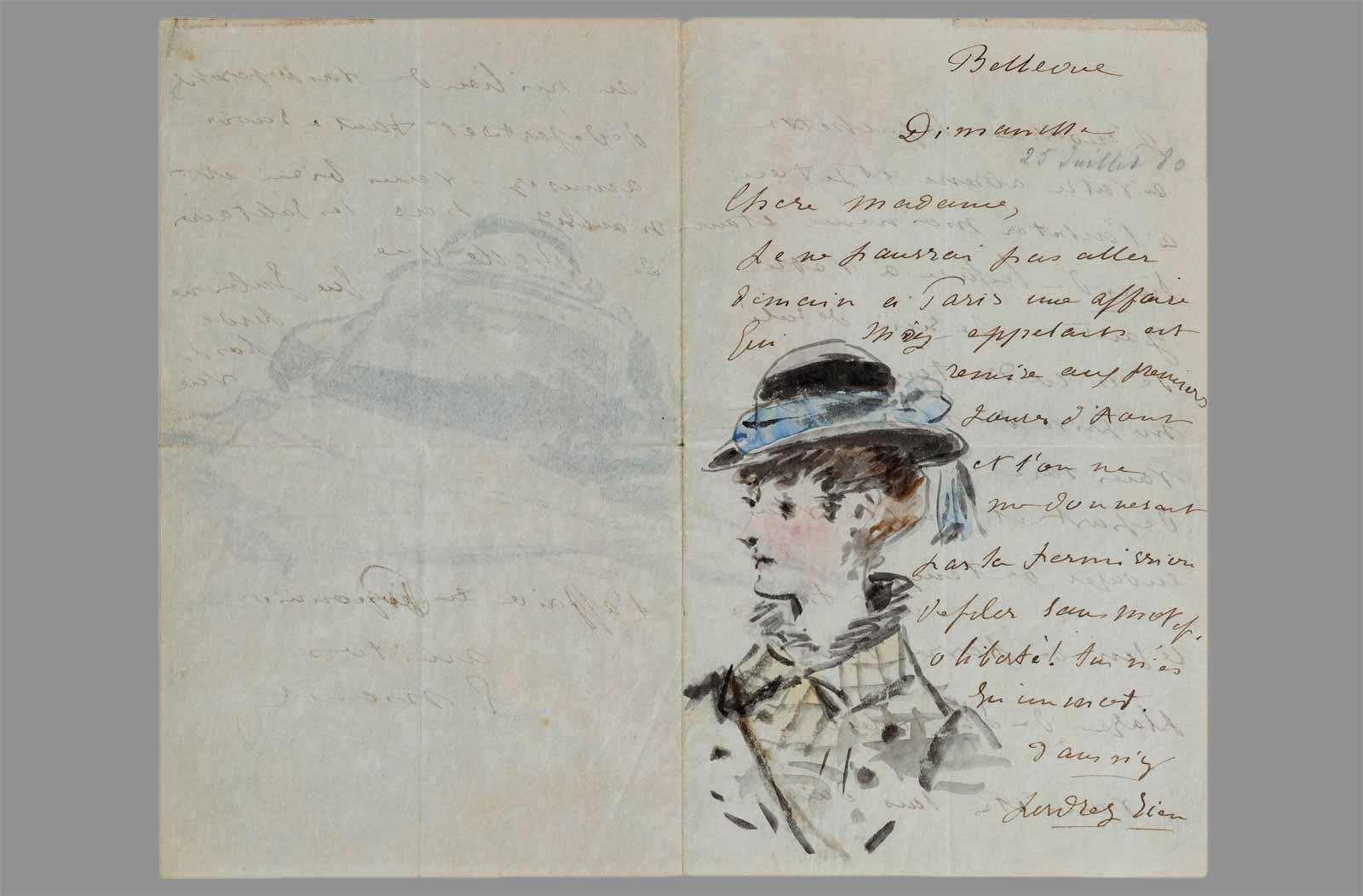

Much to history’s loss, Manet’s late work has rarely been shown together. That has recenlty been corrected thanks to a 2019 exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago—the first-ever to examine the artist’s final decades and stylistic transformation. Titled Manet and Modern Beauty, it is an unapologetic celebration of visual pleasure that also offers insight into the private struggles of one of art history’s most famous painters. On view were famous works such as Boating—a picture of bourgeois leisure that adopts the light brushwork and palette of the Impressionists—but also lesser-known works, including a group of letters illustrated with charming watercolors.

So what does modern beauty mean, in the context of this show?

“A sense of fashion and spontaneity—of being in the moment,” says Gloria Groom, the Art Institute’s curator of nineteenth-century European paintings and sculpture. “For Manet, modern beauty is everything that has to do with freshness of expression, not only in the technique, but in subject matter. It’s a very feminine viewpoint, in certain ways.”

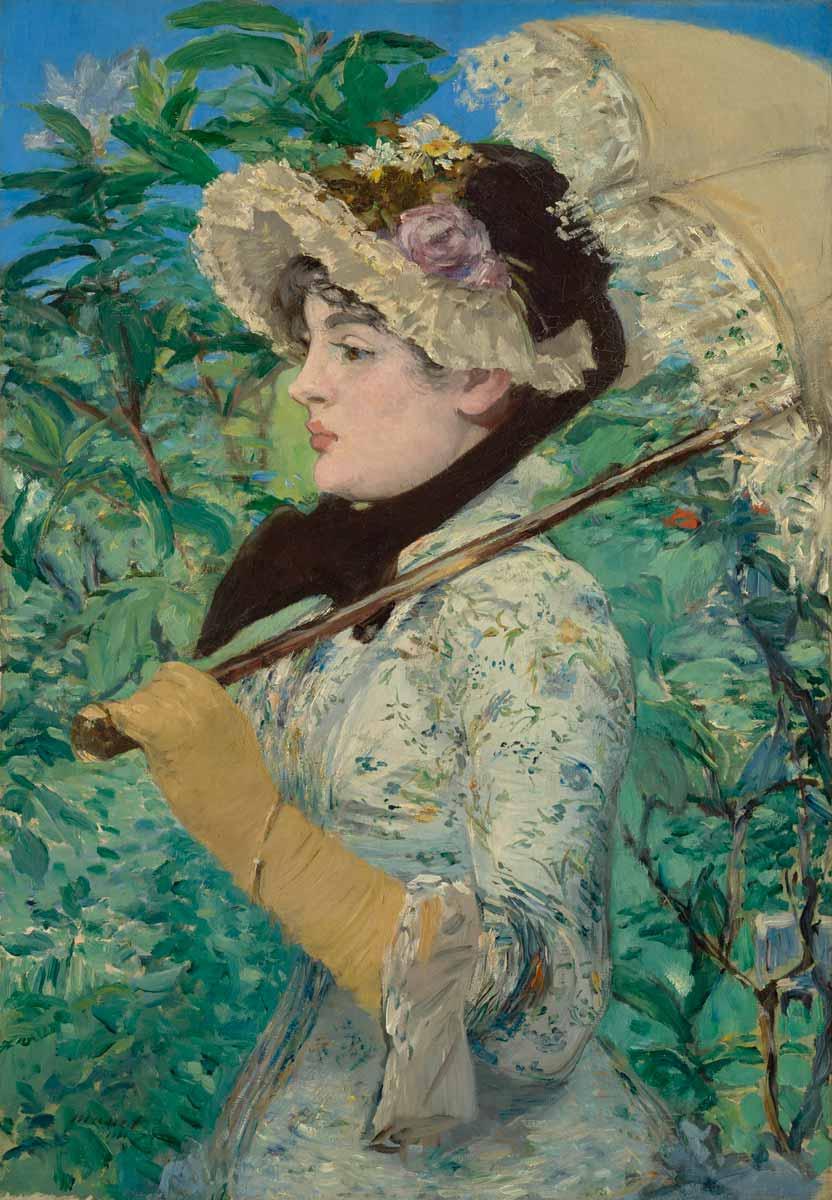

No work exemplifies this perspective more than Jeanne (Spring) (1881), the show’s star, a painting that has spent the majority of its life in private hands (the J. Paul Getty Museum purchased it in 2014; the exhibition will traveled there in October 2019). The lush portrait portrays the budding actress Jeanne Demarsy, known then as Anne Darlaud. She sat for Manet at age sixteen, but appears like an adult—a sophisticated Parisian lady in the prime of her life. She is stylish, her gloved hand gently gripping a frilly parasol, although her delicate face is also protected by a chic, ornate bonnet. Nature flourishes everywhere, from the blossoms adorning her head to the flowers decorating her dress, which almost blend into the wall of rhododendrons that makes up the background.