What sparks an artist? More to the point, what sparks Marjorie Welish? Clearly, it is she who ignites the multitude of sparks in diagrams and constructions, drawings and plans, paintings and prints, essays and poetry—and lots of opinions, sharp as well as round-edged and generous.

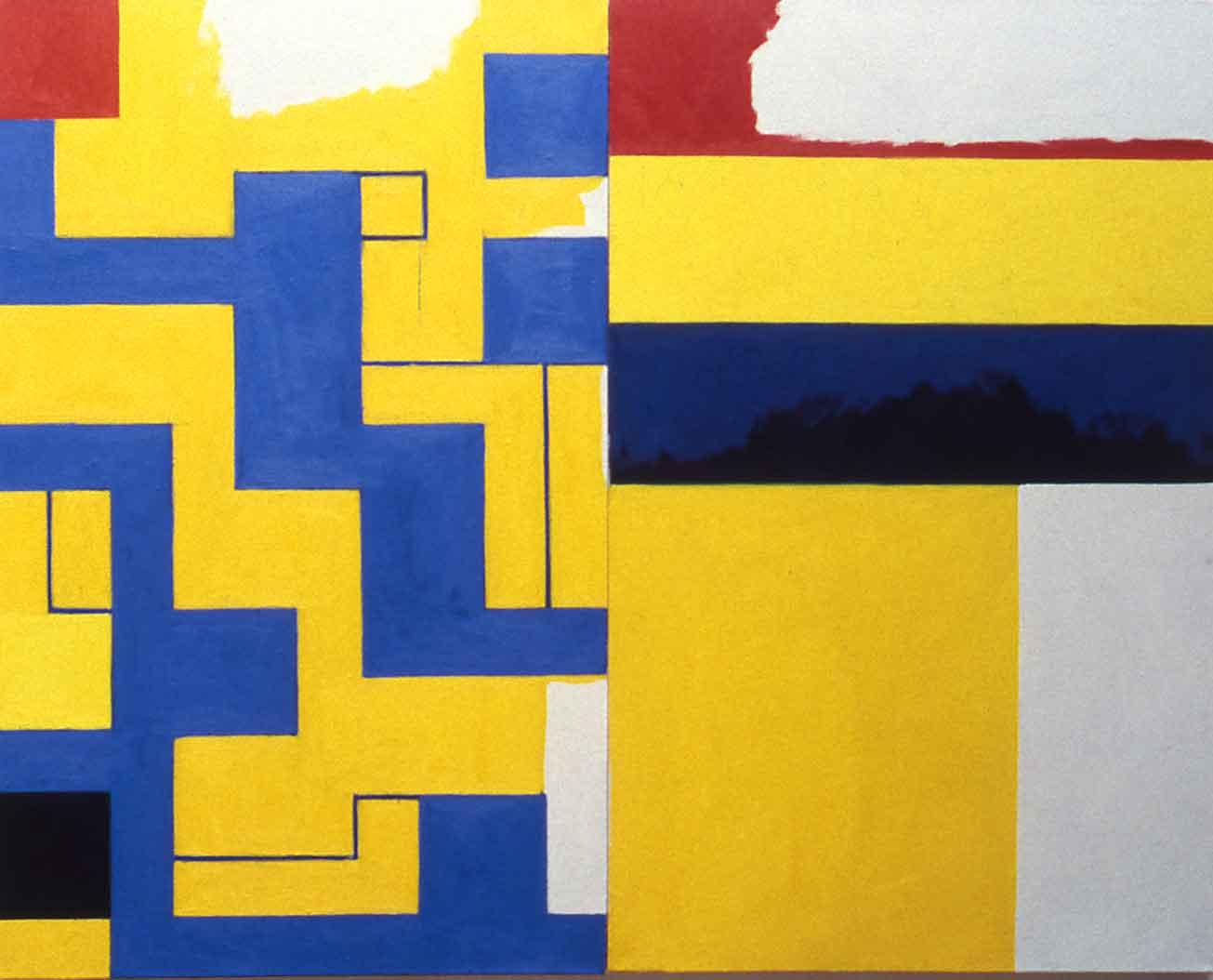

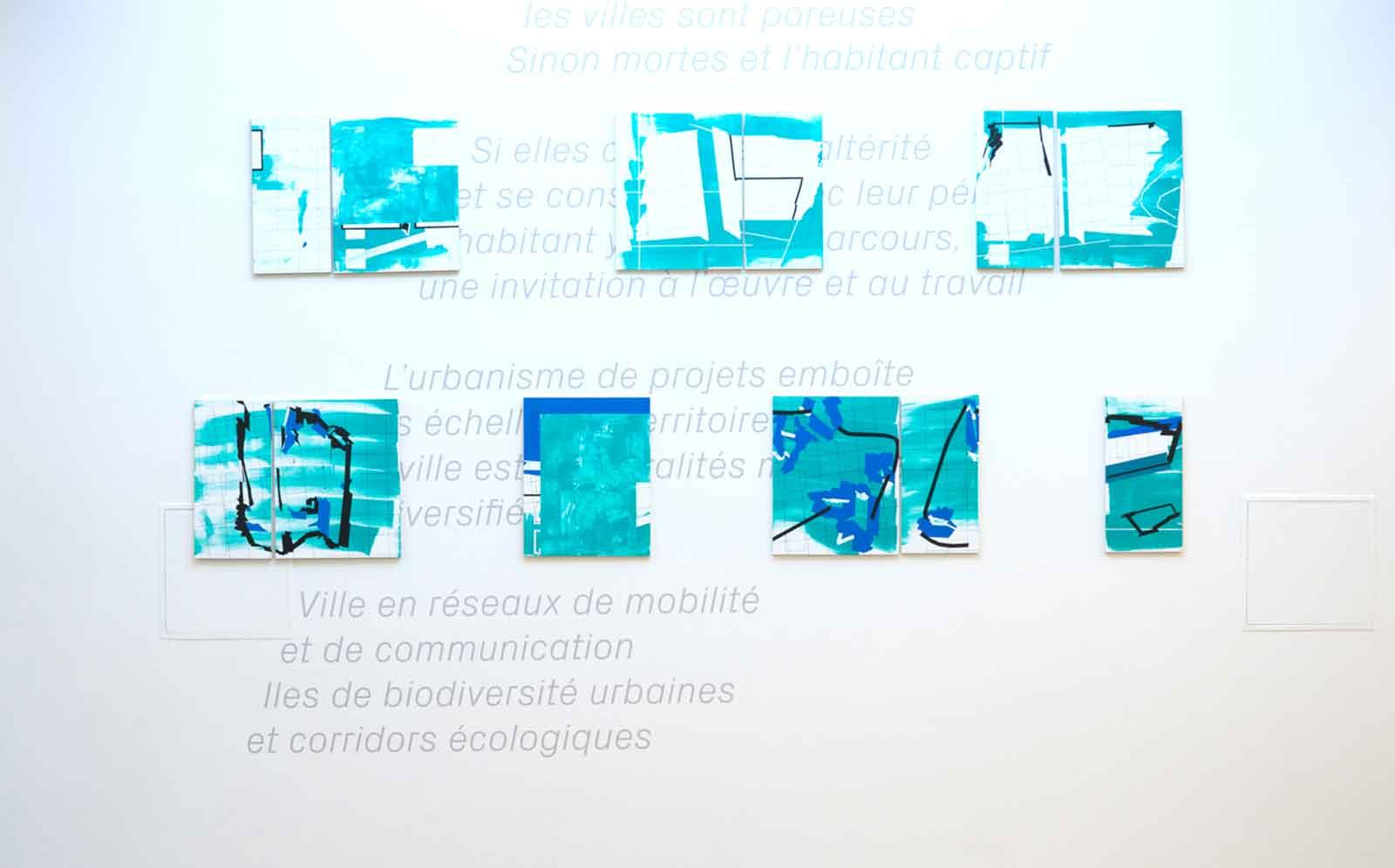

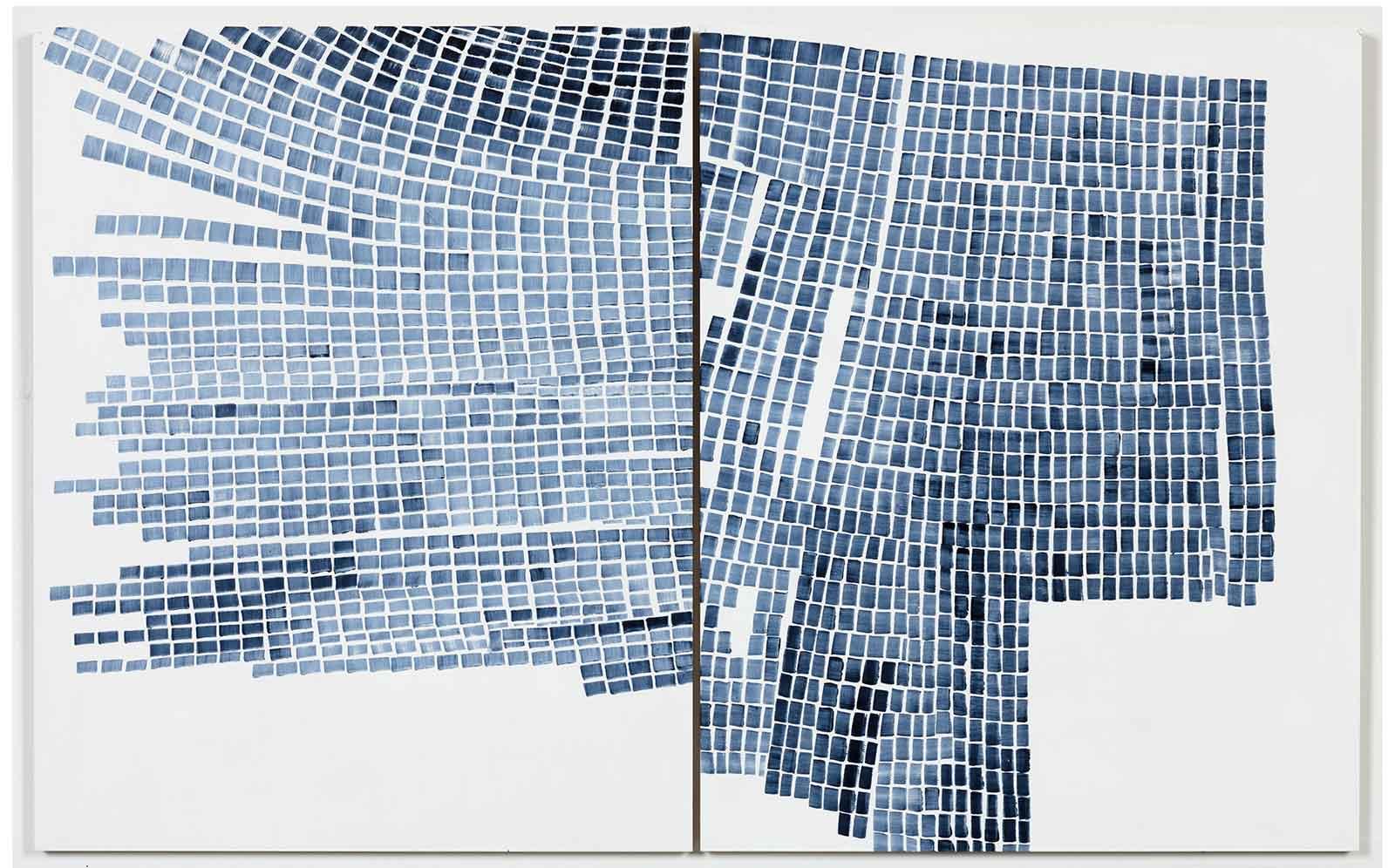

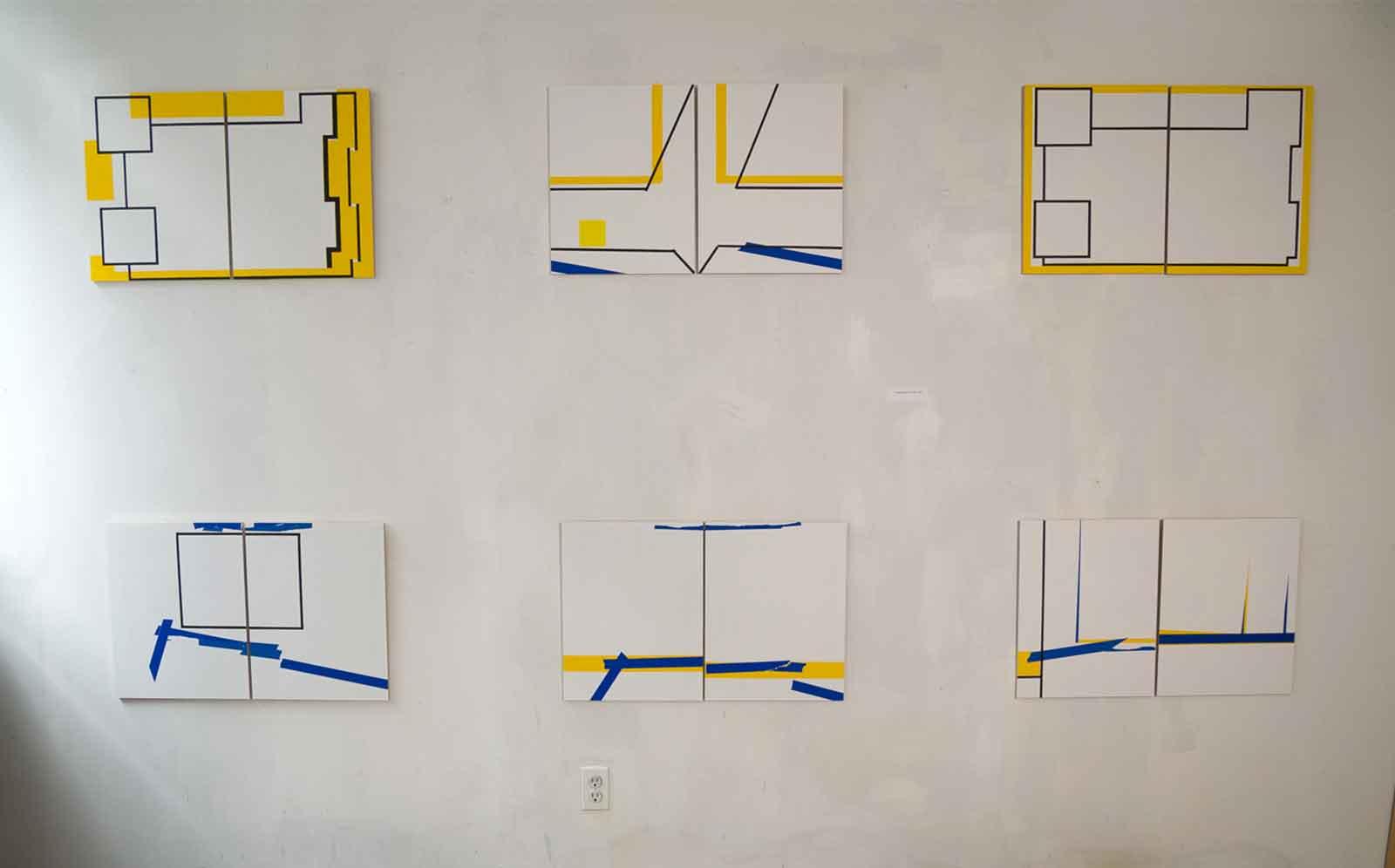

She ponders such mind-boggling questions as “Can art think?” And answers, “Yes, if it is mindful of principles. Yes, to the extent that formalism—that is, of composing with lines and planes, surfaces and volumes—can expand its compositional field by integrating structures from disciplines other than art.”

This artist/art critic has been wrestling with these ideas throughout her multifaceted career and has brought them into the present, where the look of the digital world holds sway alongside the slower, analog one.

Her work is in the collections of the British Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and she has been awarded fellowships and grants from such organizations as the Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation, the Elizabeth Foundation for the Arts, the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and Trust for Mutual Understanding, as well as a Fulbright Senior Specialist Fellowship to teach at the University of Frankfurt.