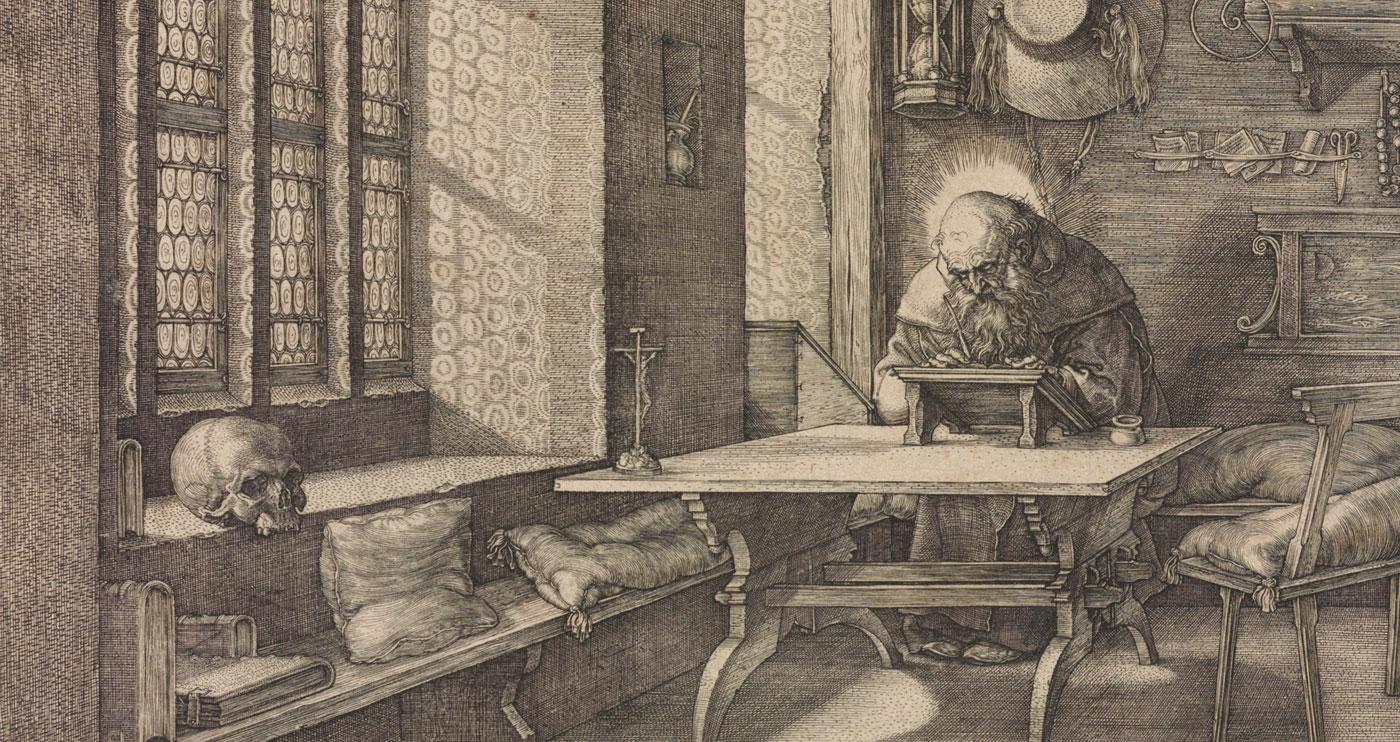

In 1520, during a stopover in Cologne on his way to the Netherlands, the painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer bought himself “a little ivory death’s head,” he reported in his journal. It was not a peculiar purchase for the time. The sixteenth century witnessed a proliferation and popularization of art illustrating macabre themes, which often took the form of skull-shaped ivory beads and miniature skeleton sculptures. As we came to learn in the Bowdoin College Museum of Art’s 2017 exhibition, The Ivory Mirror: The Art of Mortality in Renaissance Europe, these spine-chilling curiosities served a purpose.

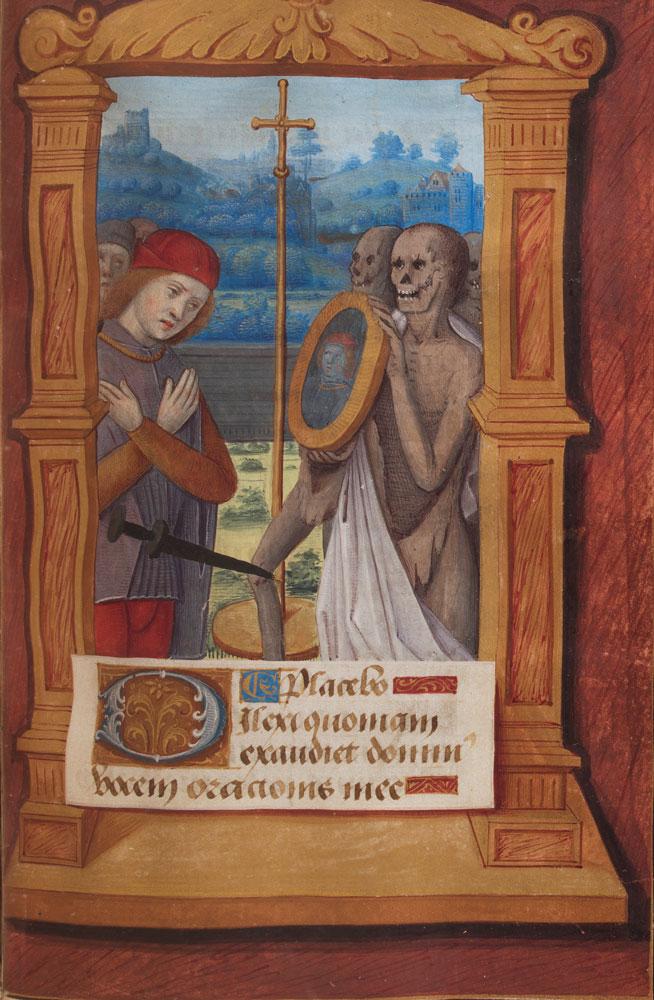

“This exhibition seeks to explain the appeal of artworks like these, pieces that seem to cut against our notion of the Renaissance as an optimistic age. We categorize them in general terms as memento mori images, images meant to remind us of the inevitability of death,” said Bowdoin professor of art history and exhibition curator Stephen Perkinson during a keynote speech at the exhibition’s opening. Put more gently, these objects and images warned their owners to enjoy life and act honorably, because the Grim Reaper might appear on the doorstep at any moment.

The Ivory Mirror brought together seventy examples of memento mori from European and American collections, offering an unprecedented view of this easily misinterpreted genre. Anne Collins Goodyear, co-director of the museum, commented, “The research of curator Stephen Perkinson and his collaborators sheds new light on these fascinating objects, enabling us to better understand the complex origins and associations of memento mori imagery, the larger artistic and literary context of which they were a part, the nature of the workshops that designed them, and, ultimately, how these remarkable works of art continue to evoke the tension between pleasure and responsibility in a fashion just as compelling today as five centuries ago.” The research was indeed staggering, and this installation was exceptional in concept and scope.

Contrary to historical speculation, Perkinson said he doesn’t believe that memento mori imagery is a direct response to the Black Death pandemic of the fourteenth century, but loss of life by disease, childbirth, or mere accident was persistent and highly visible throughout the Middle Ages. Piety, one of the exhibition’s eight main themes, was no antidote to this, yet it clearly soothed hearts and minds to pray using devotional aides such as rosaries. Some of the carved ivory beads displayed were used in such a manner, as part of a larger chaplet or pendant. These pieces depict the head of a lively person or couple, that, when turned, delivers a ghastly surprise on the other side: the same face stripped of its skin, riddled with worms and other creepy-crawlies. If that sounds morbid, consider the crucifix that terminates a contemporary rosary—is a corpse nailed to a cross not comparably grim?