The Mohamed Mahmoud Khalil Museum was even more grand by night. Built in 1915 using elements of the Art Nouveau style of architecture, the four-story villa, once owned by politician turned art patron Mahmoud Khalil Pasha, was adorned with glass and metalwork fixtures at the entrance, while its eastern side faced the River Nile, glistening beneath the crescent moon. Spotlights and lampposts peppered the garden leading towards the entrance, guiding us towards a state-of-the-art exhibition hall—the largest of its kind at the time in Egypt—where a tribute was being held for my grandmother, Menhat Helmy.

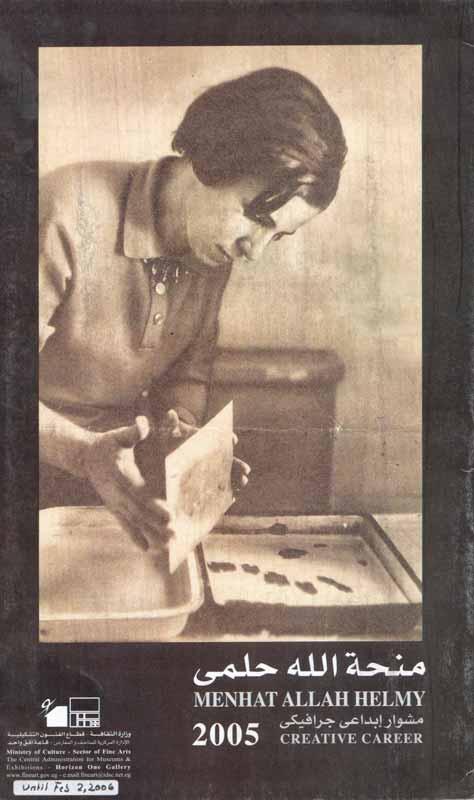

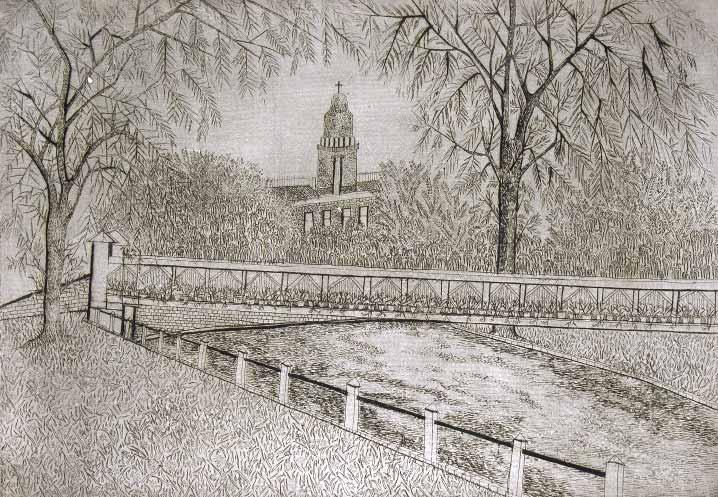

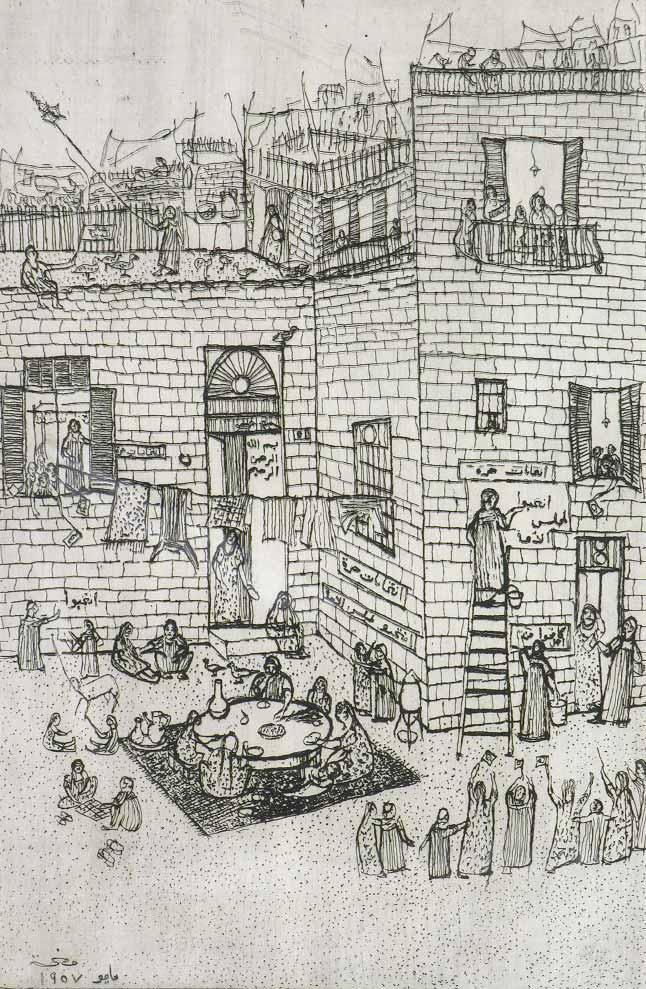

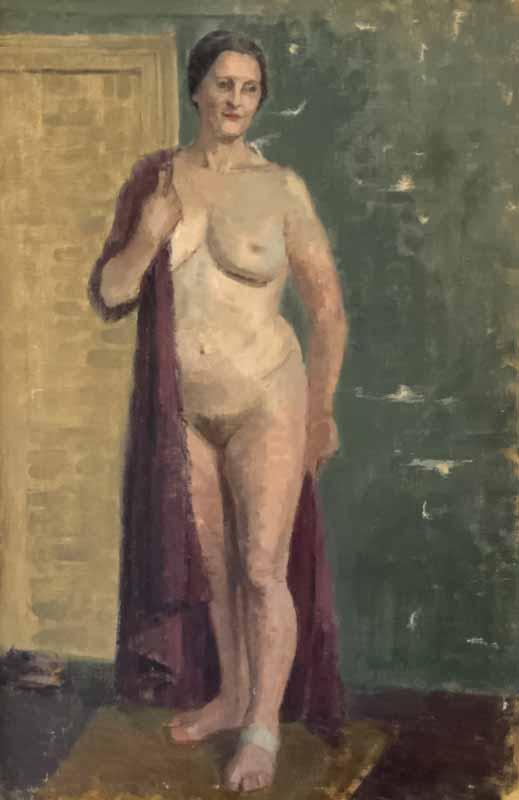

The historic exhibition debuted in December 2005, eighteen months following the pioneering artist’s passing. The retrospective show, which brought together a career’s worth of artworks ranging from sketches, portraits, and paintings, to sculptures and abstract etchings. It was the first time that the vast majority of Helmy’s oeuvre had ever been on display in a single setting—a career spanning four decades laid bare for all to see. It was an unveiling that helped resurrect the career of an artist who was all but lost to the annals of old exhibition catalogues and cemented her status as a pioneer during the golden age of modern Egyptian art.

Though I was only thirteen years old at the time, I have vivid memories of the opening night. I attended the exhibition along with my mother, Sara—smiling from ear to ear as she took in her mother’s work, seeing some of the pieces for the first time in decades—and my brother, Rami. Many of Helmy’s brothers and sisters who had succeeded her were also in attendance. I recall the ribbon-cutting ceremony with then Minister of Culture Farouk Hosny and the endless sea of faces that filled the exhibition hall shortly thereafter.