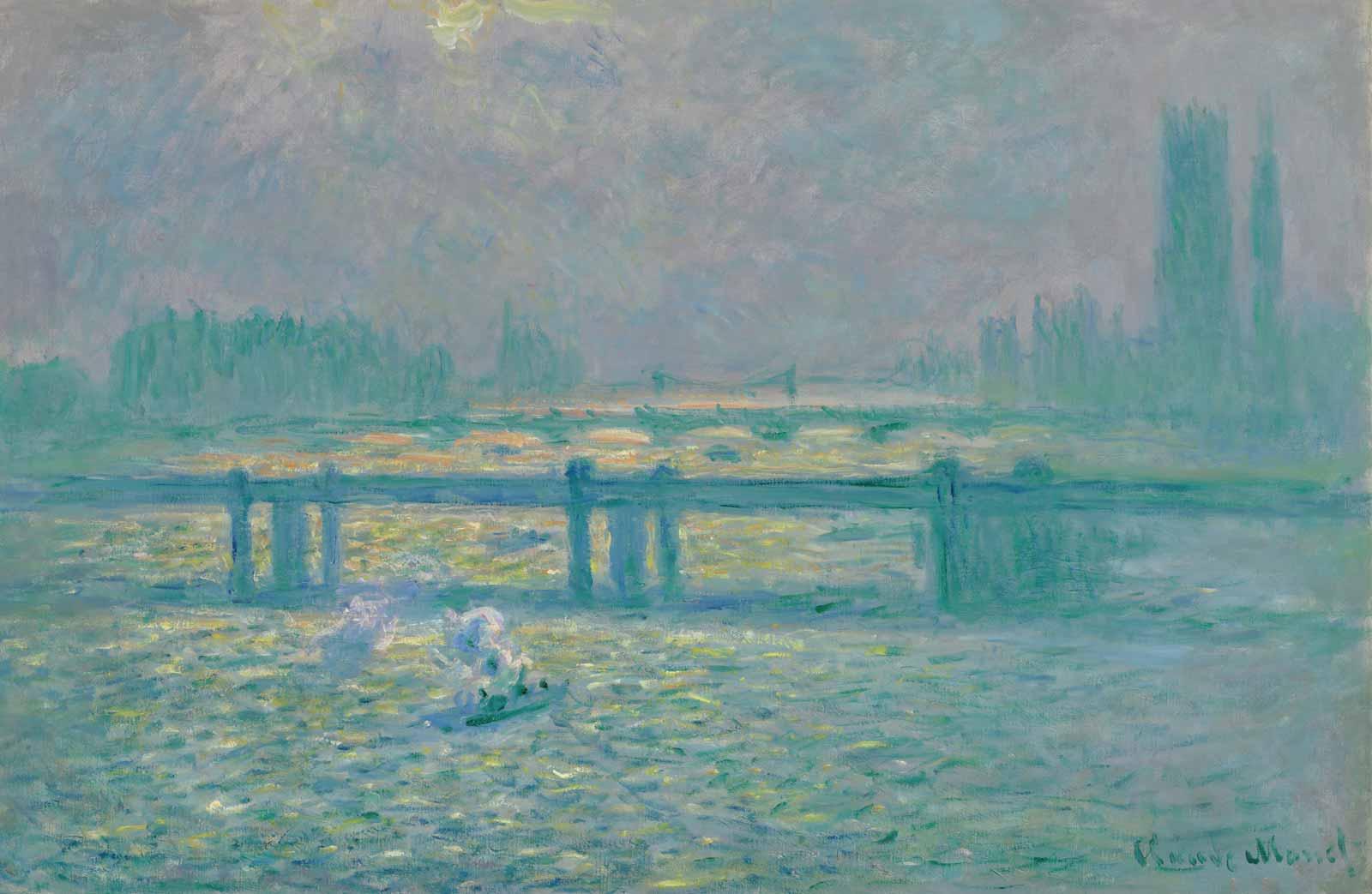

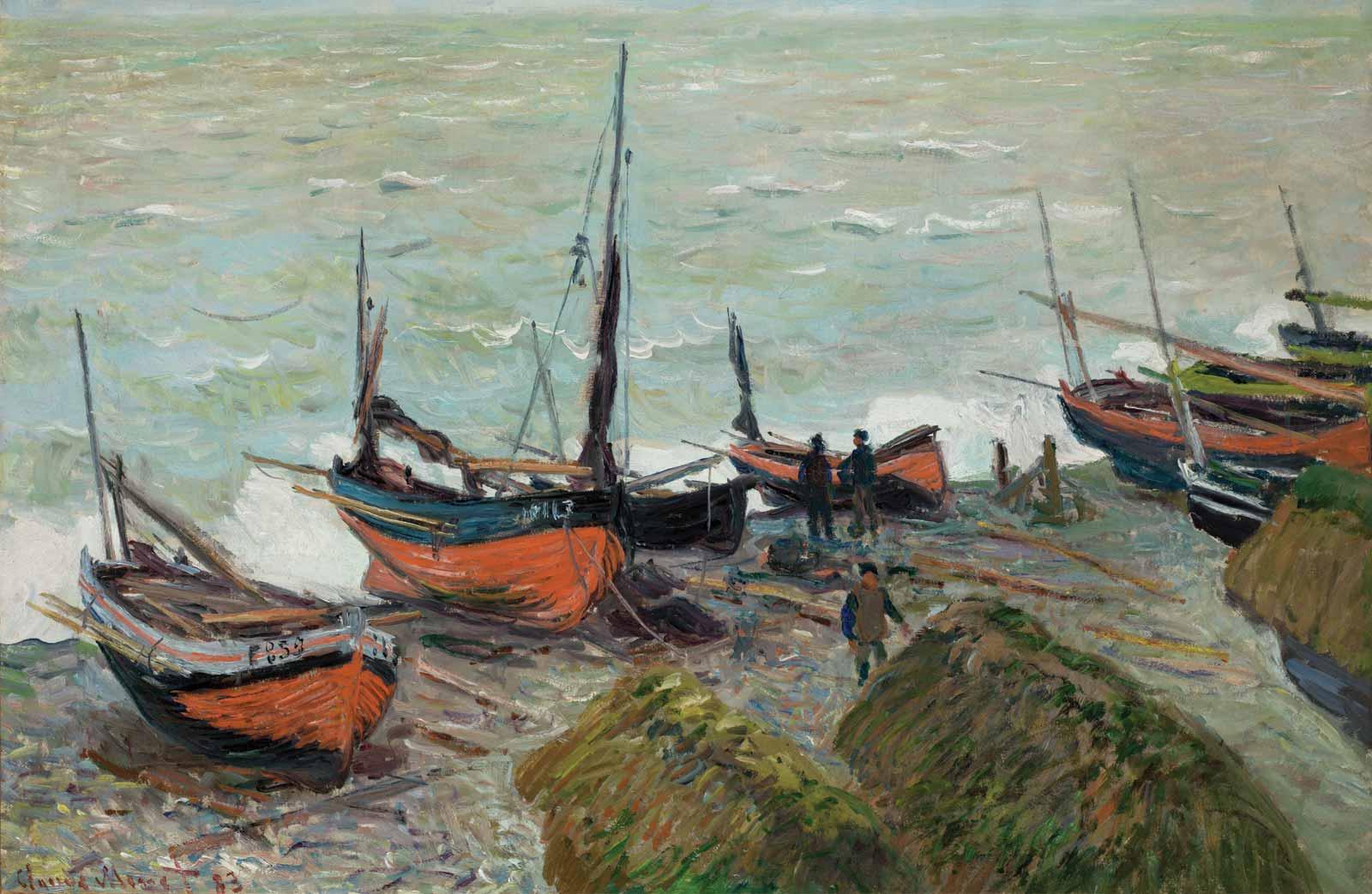

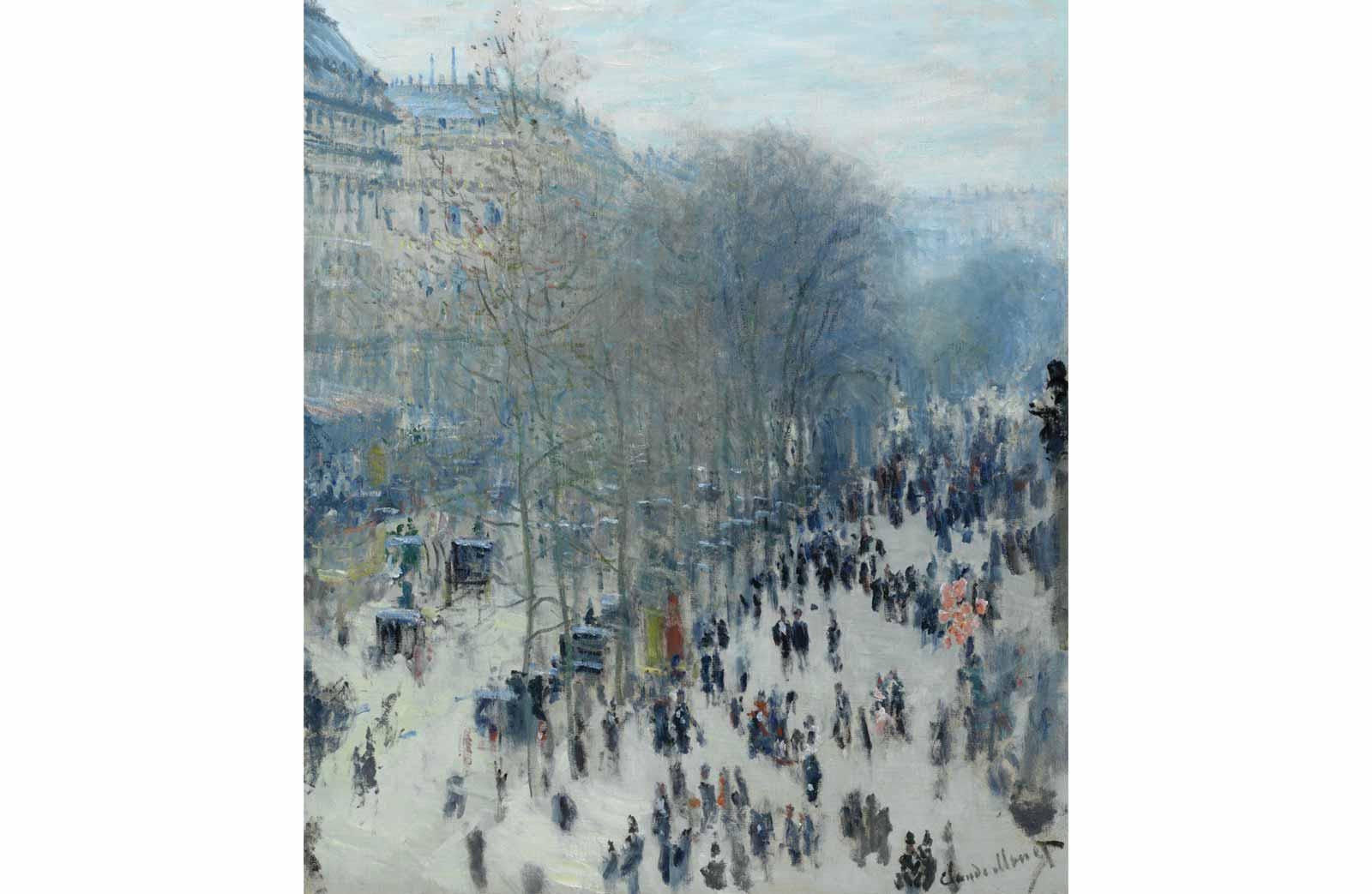

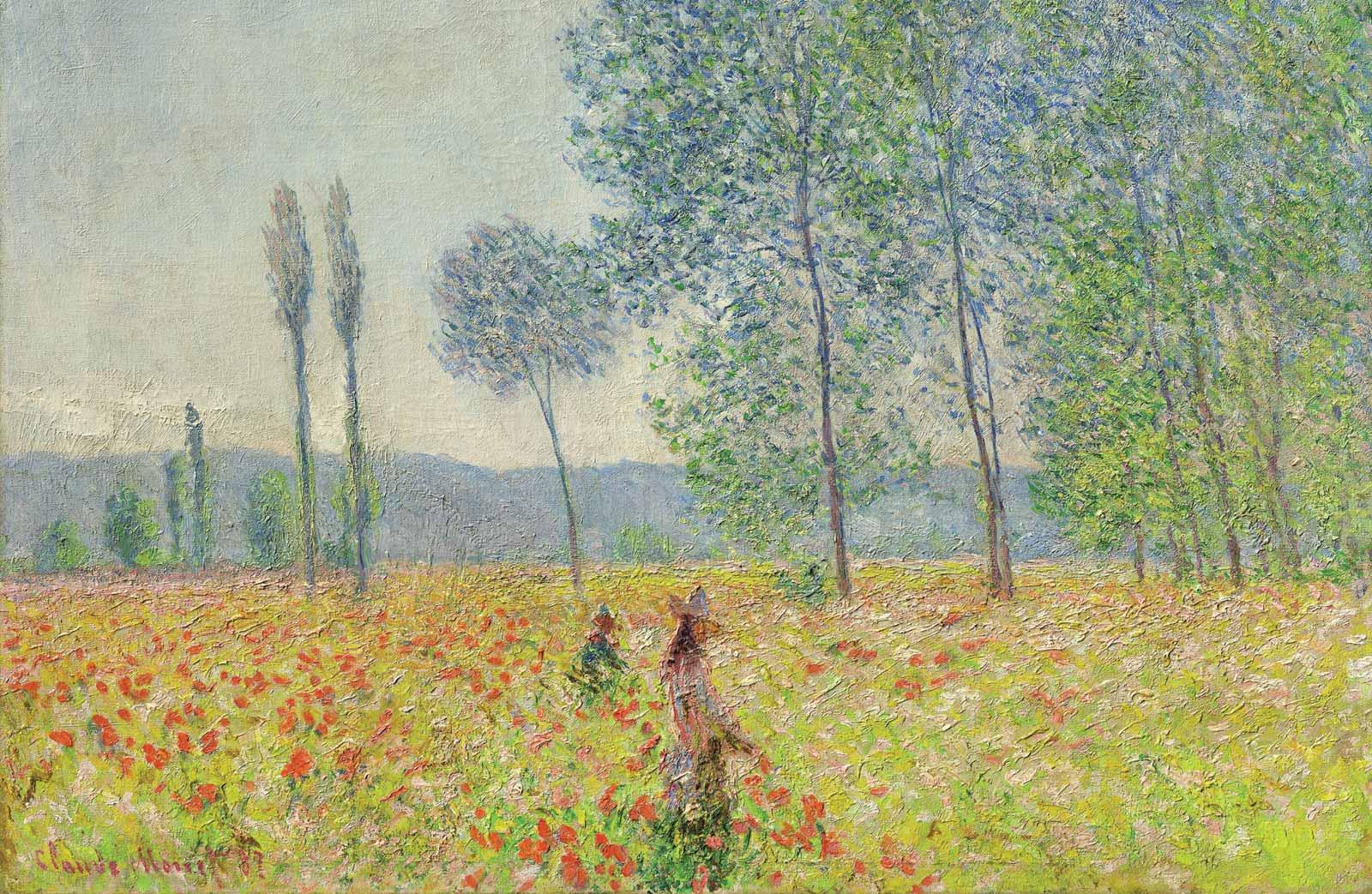

Claude Monet has captivated the art world with his innovative Impressionism for over a century. But the prolific landscape painter was also a prolific letter writer. The French artist’s correspondence allowed curators to better get to know the man in question for Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature—the most comprehensive exhibition of his works in roughly twenty-five years, on view at the Denver Art Museum (DAM) October 21 through February 2, 2020.

The DAM’s Curator of European Art Before 1900, Angelica Daneo, hails from Italy, near the border with France. Fluent in French, Daneo read Monet’s missives with nothing lost in translation.

“I like to start, if available, from primary sources and words of the artists—letters, in the case of Monet. All of his letters were published in French,” Daneo said. “For me, personally, that was an important starting point.”

Daneo acknowledged that there is a vast scholarship surrounding Monet’s work and admitted she wondered what the DAM could add to the deep well of research and critique.

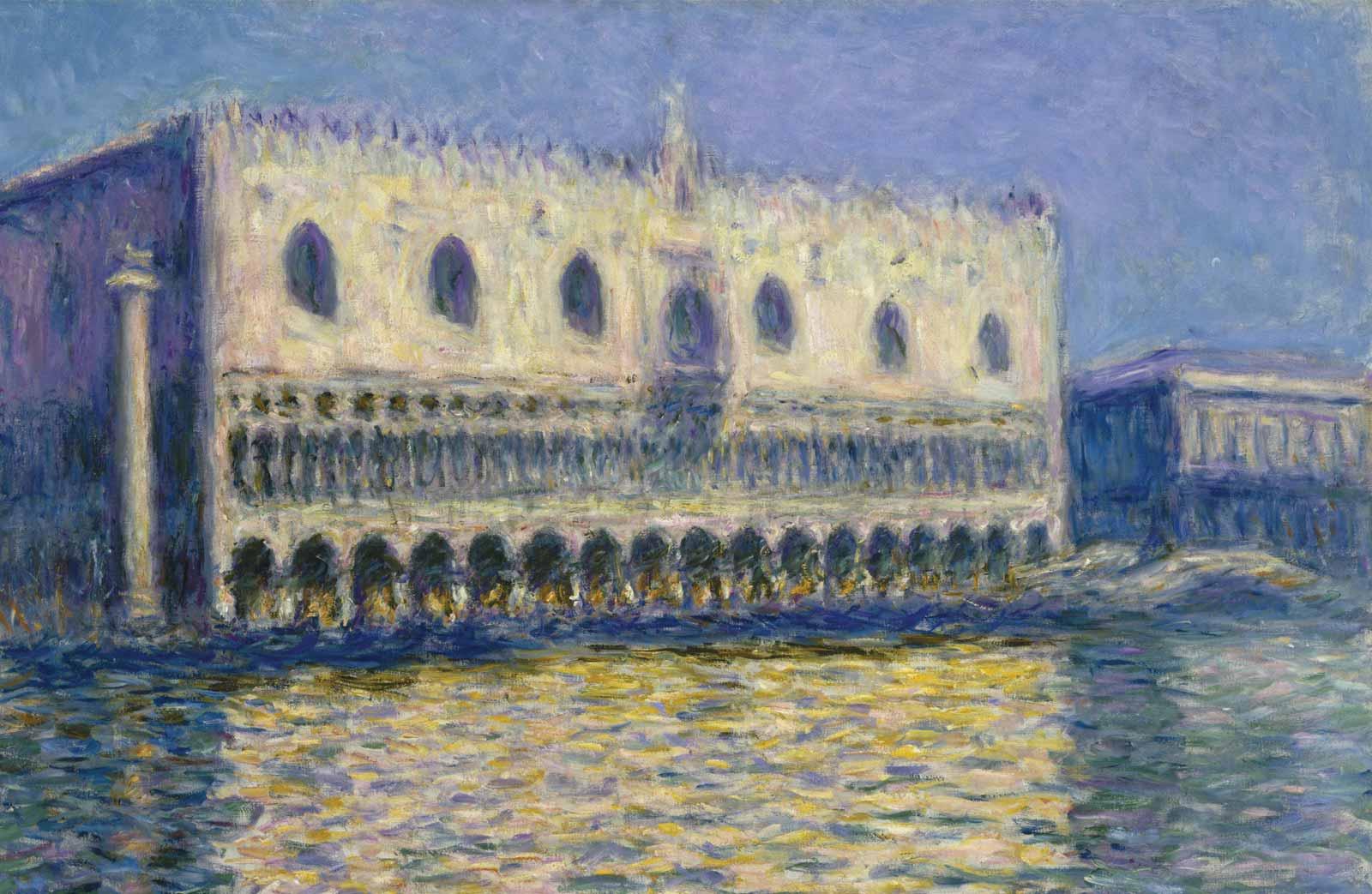

“To contribute, we wanted to be able to go back to the beginning and form our own opinions. The letters were extremely helpful. I had to read the originals, otherwise I was missing his recurrence of eagerness to grasp the spirit of a place,” Daneo said.