The location of a museum can reveal quite a bit about the image it wants to project: prestige locations, like Fifth Avenue, suggest that the collection is highly established. A sleeker location near commercial galleries associates the museum with younger, contemporary practices.

Then there’s The Museum of Socialist Art in Sofia, Bulgaria. It’s crammed between the Bulgarian equivalent of the DMV, a relic of the communist era, and a modern office building emblazoned with the name of a major pharmacy company. The location is appropriate—Bulgaria’s only museum dedicated to displaying works of Socialist realism is literally stuck between the communist past and the capitalist present.

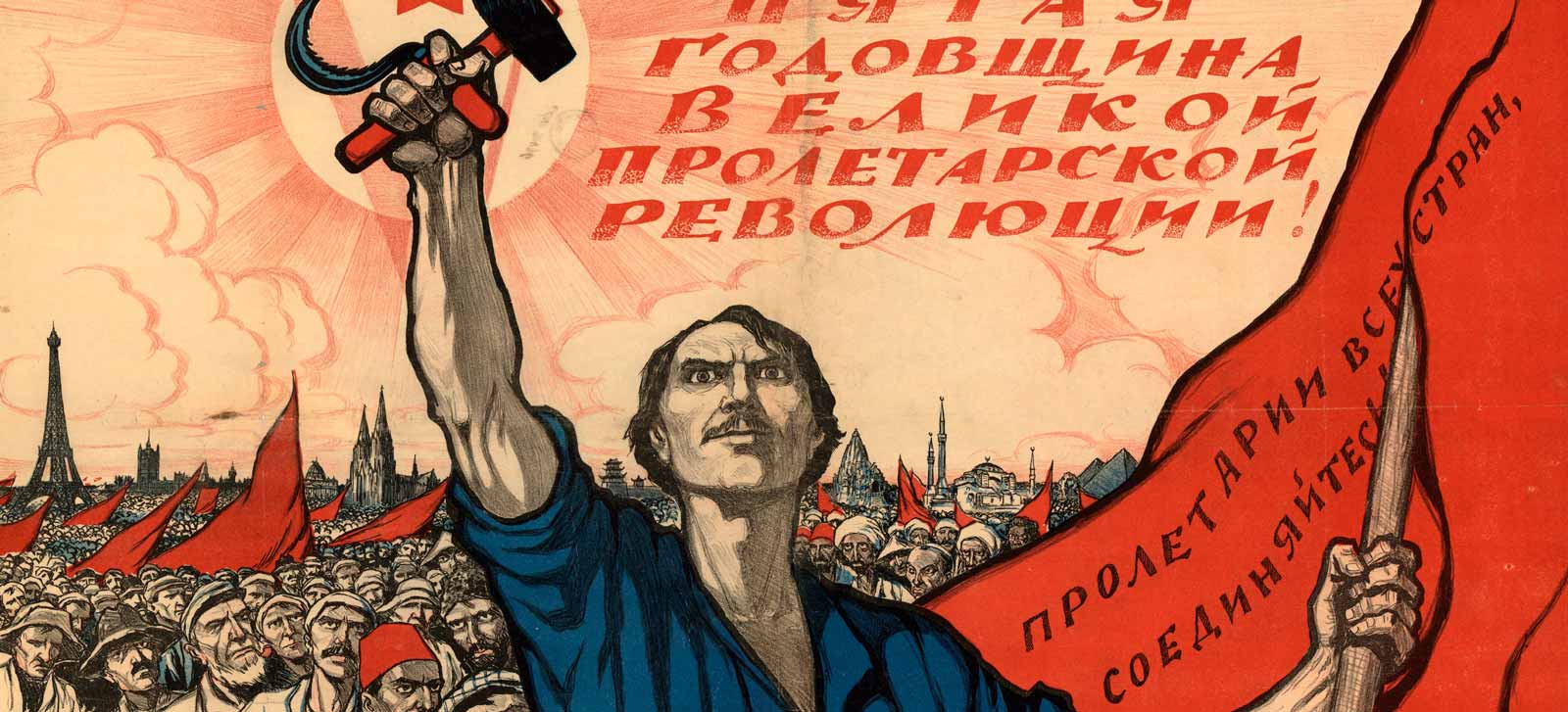

The Museum of Socialist Art is divided into two sections. The interior exhibition space features a mix of Socialist realist works on canvas, and propaganda from Bulgaria and other communist countries. Outside, a large sculpture park displays communist-era statues from around the country. During communism, these statues were ubiquitous in Bulgaria. Most towns and cities, regardless of size, commissioned monuments to communist icons like Lenin and Todor Zhivkov, the country’s longtime dictator.