A smooth, undulating white stone structure juts out into the street like an iceberg in downtown Winnipeg. Here, hundreds of miles south of the Canadian Arctic and Nunangat (the Canadian Inuit homeland territories), is the world’s largest collection of contemporary Inuit artworks. This postmodern iceberg is Qaumajuq, the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s newest addition: a 40,000 square foot museum-within-a-museum entirely dedicated to Inuit carvings, works on paper, textiles, new media, and educational initiatives.

Open to the public only since March of 2021, Qaumajuq continues the Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG)’s decades-long legacy as a progressive and inclusive space for intercultural learning and gathering. Qaumajuq is an Inuktitut word meaning “it is bright, it is lit,” an apt term for the new initiative. It has already emerged as an international leader in decolonization practices thanks to its programming, design, exhibitions, and collections.

Qaumajuq’s architectural design is directly informed by a trip that architect Michael Maltzan, museum director and CEO Dr. Stephen Borys, curator of Inuit art Darlene Coward Wight, and several other team members took to Nunavut early in the center’s planning stages. It was important to everyone involved that Qaumajuq physically reflect the landscape of the communities whose work it houses. Its finished form, white granite, curved glass, and abundant light bring a glimpse of the open spaces and dramatic geography of some of Canada’s northernmost regions to downtown Winnipeg.

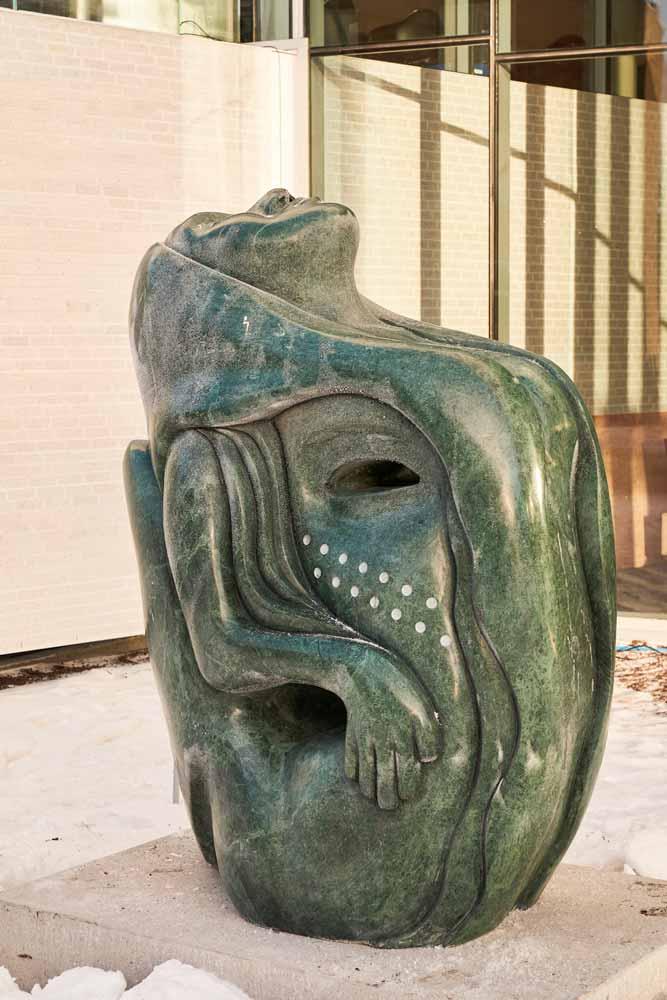

Transparency is perhaps the first word that comes to mind at Qaumajuq. The museum’s Visible Vault is a metaphor for its entire ethos. This central exhibition space is an undulating mass of glass, housing thousands of carvings around which the museum staff move in their daily work. Thanks to this vault, visitors are immediately met with the museum’s collection and inner workings right as they enter the space. The vault houses 4,500 stone carvings on multiple levels. And there are an additional 2,900 light-sensitive carvings made of more delicate organic materials below ground.