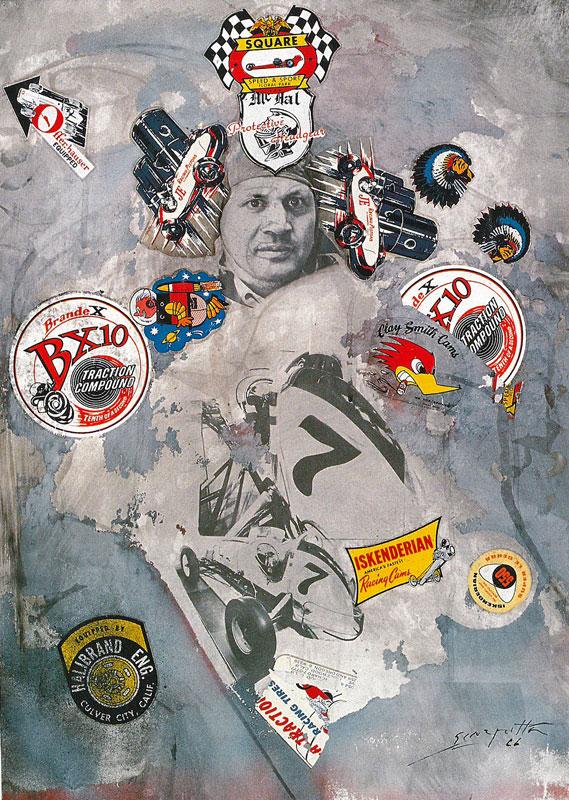

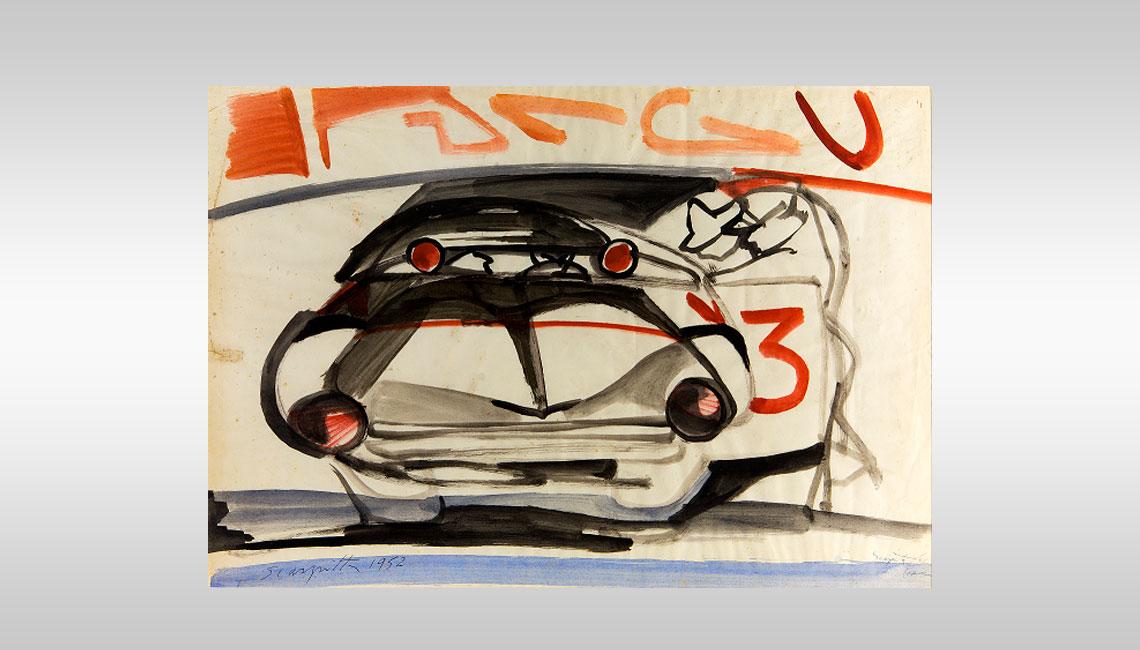

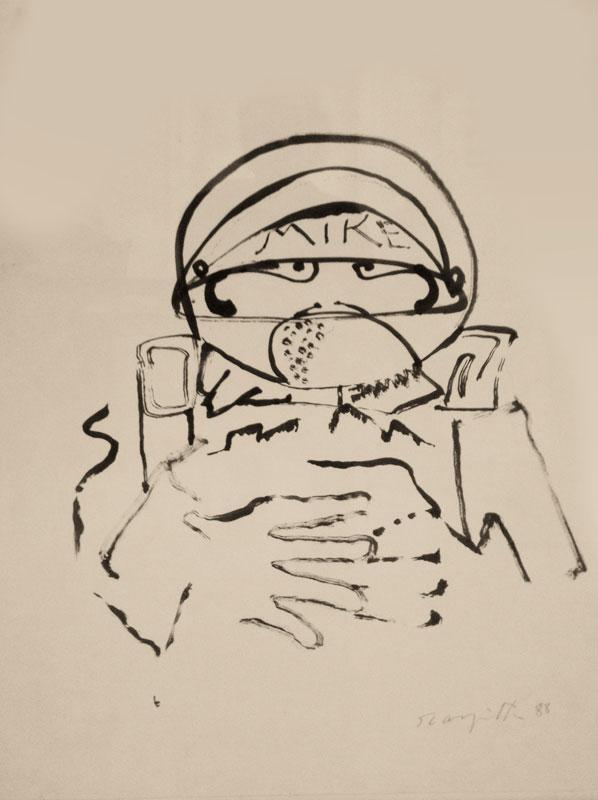

For Salvatore Scarpitta, the sport of car racing was more than an event. It was danger, excitement, courage, speed, and a lifelong fascination that turned up over and over in his art.

To understand the depth of passion an adolescent Salvatore Scarpitta had for race cars, you have to understand that Scarpitta didn’t just go to the car racing events, held near his Hollywood, California home. He went there every week—for four years. He even managed to find his way into a pit crew, though once he was discovered, the crew tossed him out.

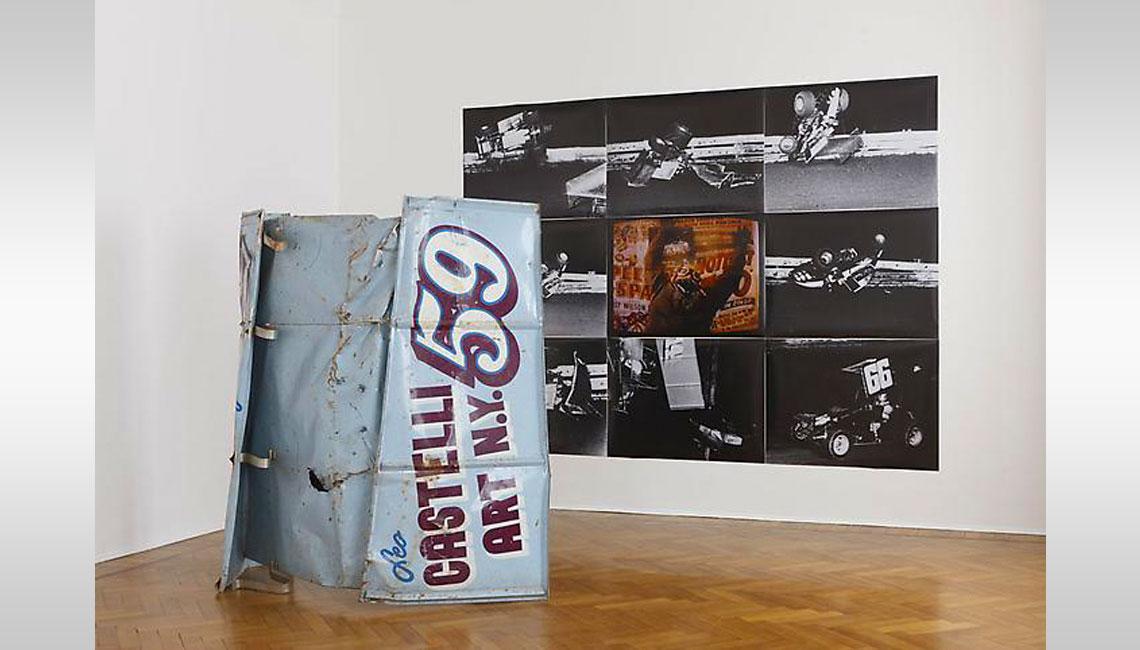

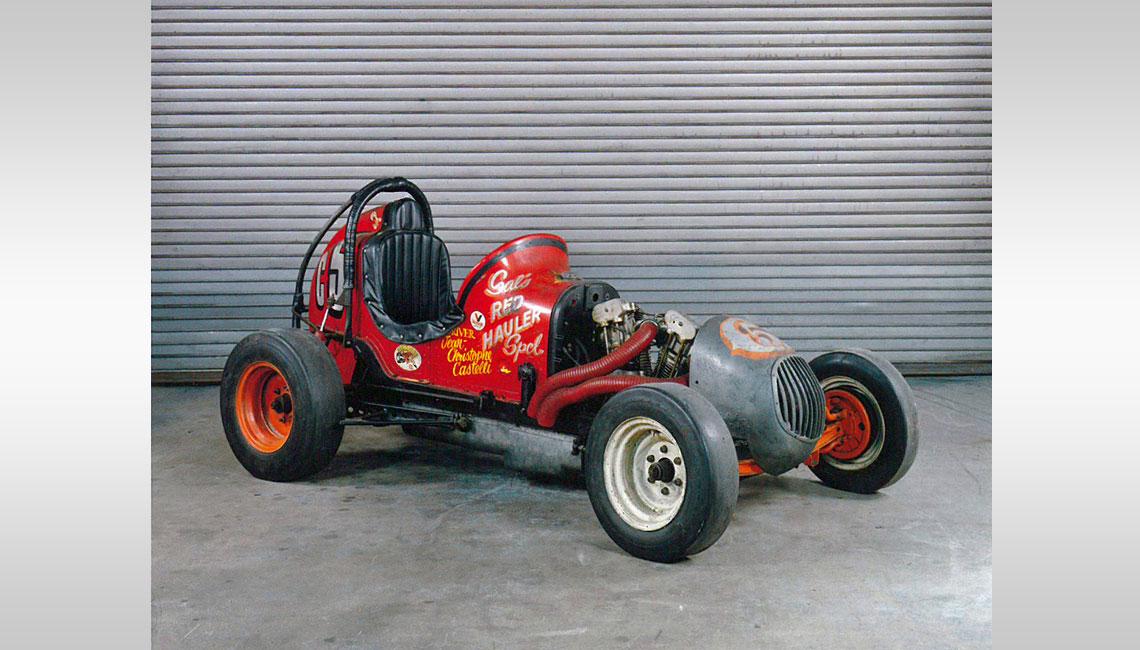

So it’s no surprise that when Scarpitta grew up and began working as an artist (he was one of Leo Castelli’s original ten artists, along with Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns), his later works would include art with racing car motifs and assemblages created from pieces of racing car wreckage. In 1964, as the story goes, he was working on one such assemblage when he realized he had pushed it as far as he could go. He immediately stopped his work and went out and built a facsimile of a race car, using original car parts, wood and plastic. “They were fabrications from found objects,” says his daughter Stella Cartaino. “He repurposed them. But they are good enough to fool true gear-heads.”

A collection of these facsimile cars went on display in 2018 at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (CAM). In fact, CAM presented the largest number of these life-size, fully-functioning works of art ever assembled in the U.S.

“Scarpitta was a man in between,” says Lisa Melandri, CAM’s executive director and the exhibit’s curator. “He came of age in Italy, and was raised during his teen years in L.A. But he went back and forth between his home country and America a great deal during his life.”