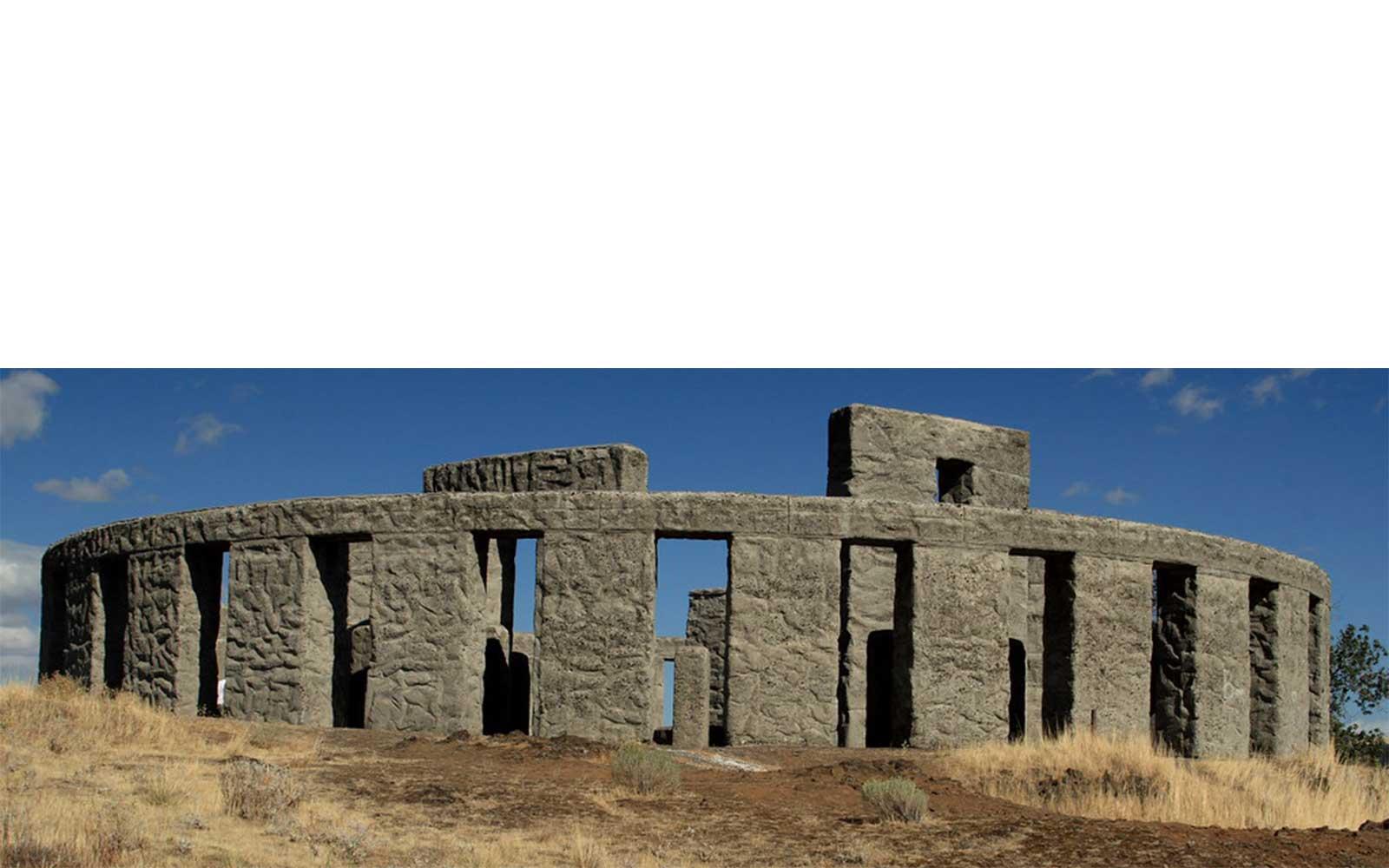

In 1918, much of the world was still in the throes of the First World War, the largest and deadliest conflict that planet had seen to-date. And yet, 1918 was also the year that the first US memorial to the war was built, in rural southern Washington State, along the steep banks of the Columbia River. Here, railroad tycoon Sam Hill decided to recreate Stonehenge as a monument to commemorate the fourteen local young men recently killed overseas.

The Stonehenge Memorial’s dramatic surroundings add to the somber weight of the site. When Hill enlisted the help of local astronomers to design this re-creation of Stonehenge, he (falsely) believed that the original Neolithic structure in southern England marked a site of human sacrifice, making it an appropriate and poetic ode to the local men who had died in the war.

Hill’s unique project aimed to connect modern events in Europe to their impact on American soil while drawing on historical design and ritual precedents. The monument has much in common with subsequent American war memorial efforts for how it requires visitors to spend time contemplating it; this modern Stonehenge does not seem immediately connected to the First World War, but like the other American memorials that followed it, its scale, location, and reliance on viewer engagement makes for a powerful memorial experience.

What is a monument? Is it the same thing as a memorial? We might think of a monument as something accessible with which we can interact in a way that suits our need to process traumatic past events. A monument holds symbolic power, both on an individual and group level, less for what it looks like and more for the events, people, and ideas it stands for. Monuments are physical, tangible vehicles upon which we can direct our memorial efforts.