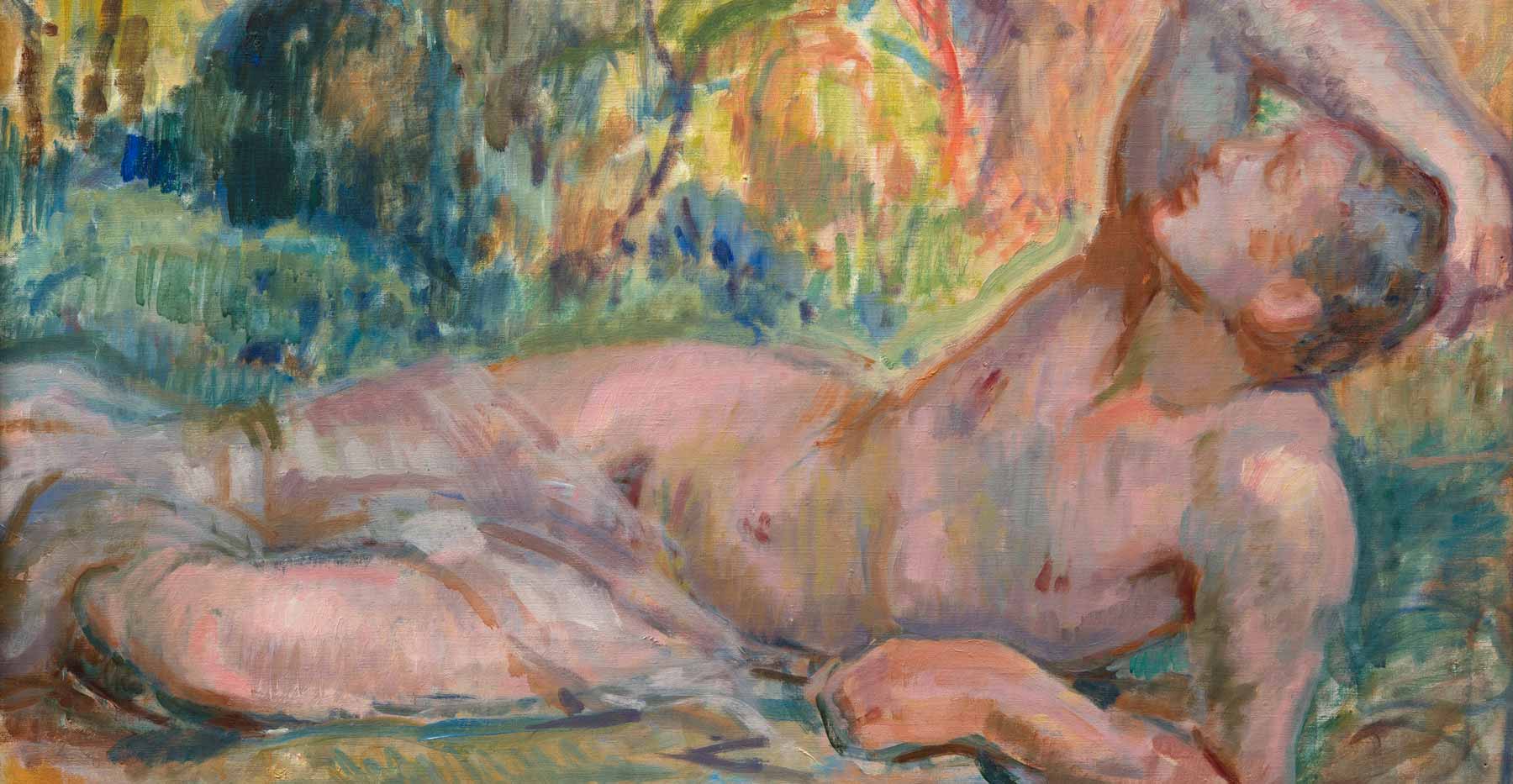

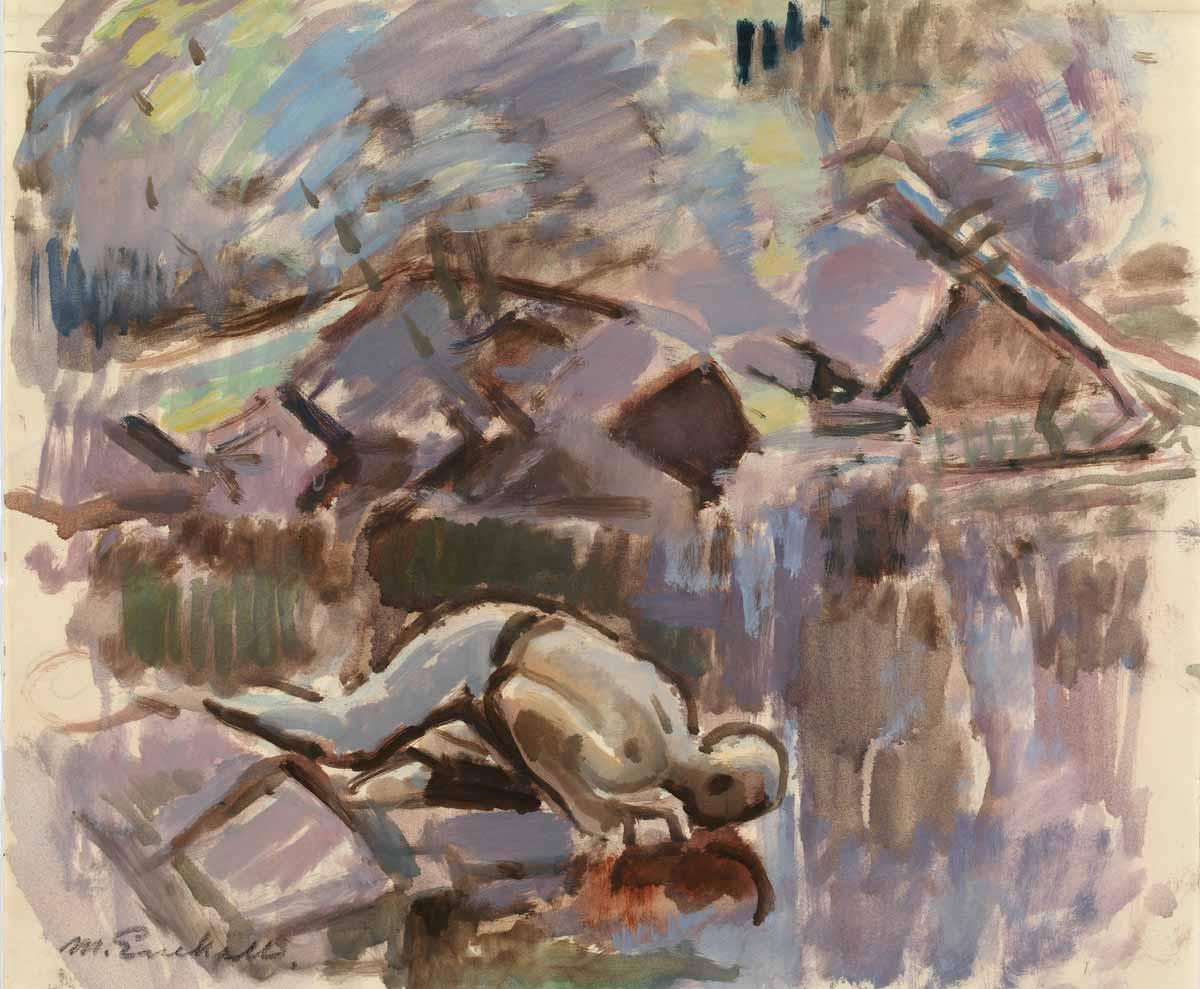

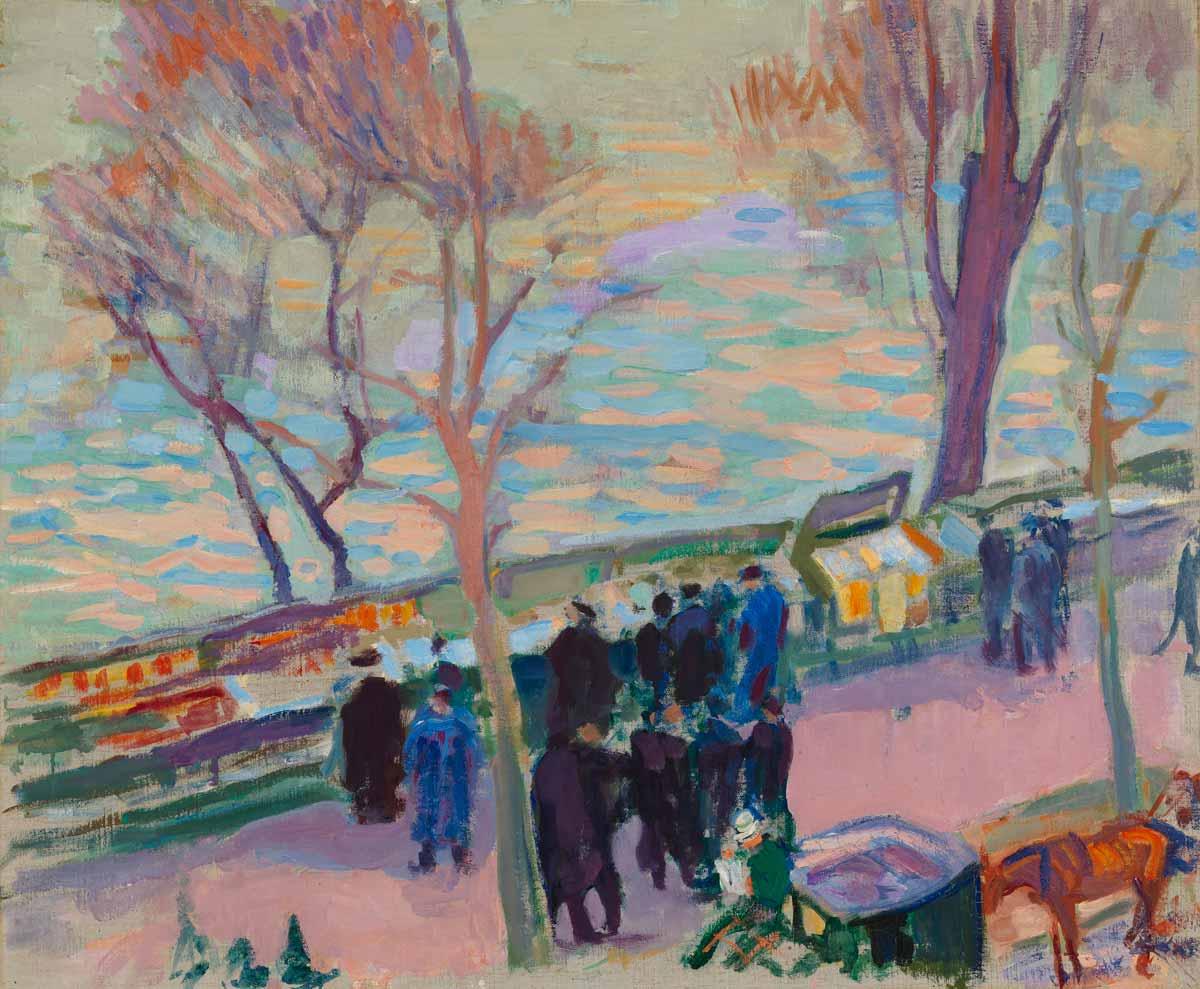

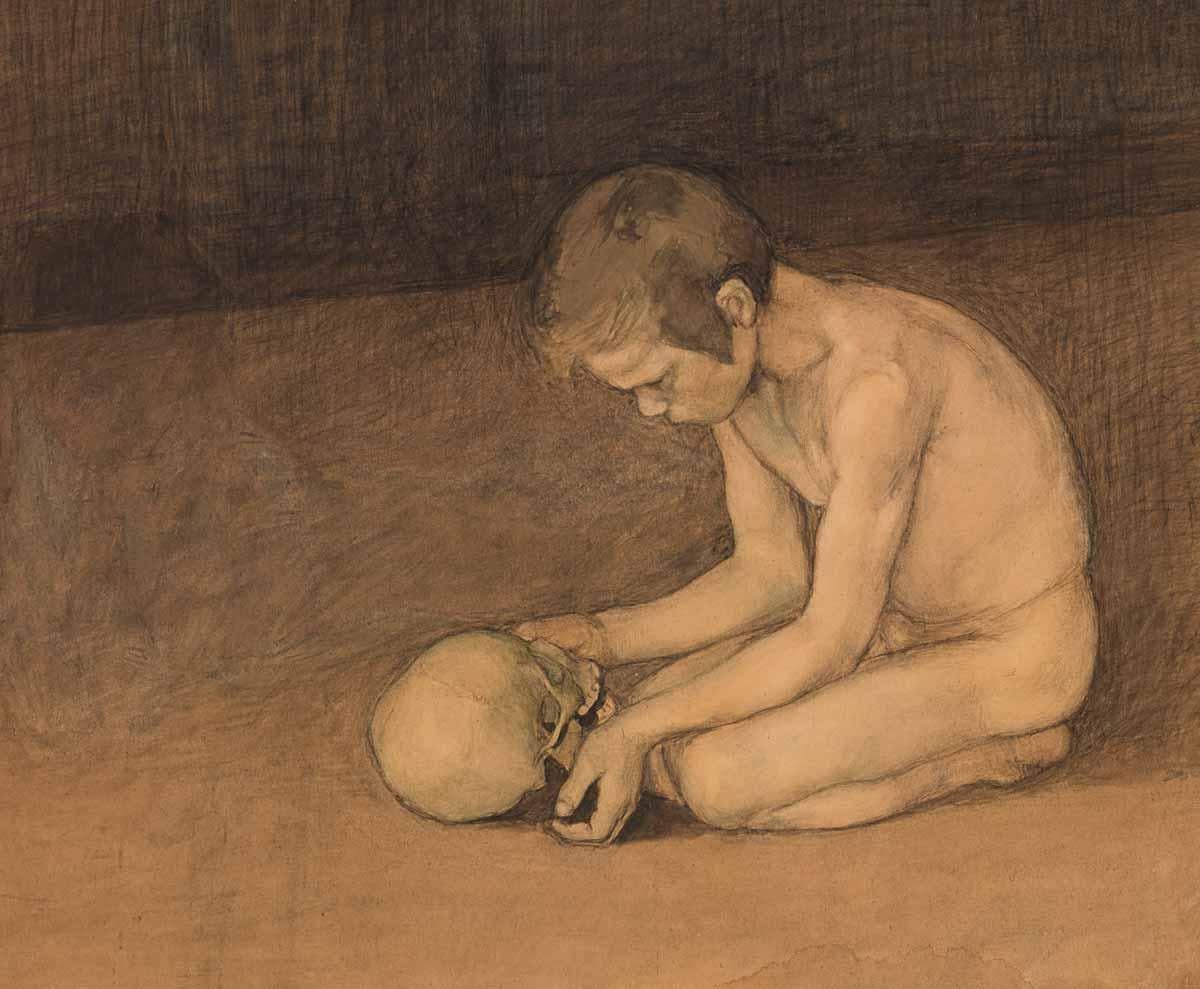

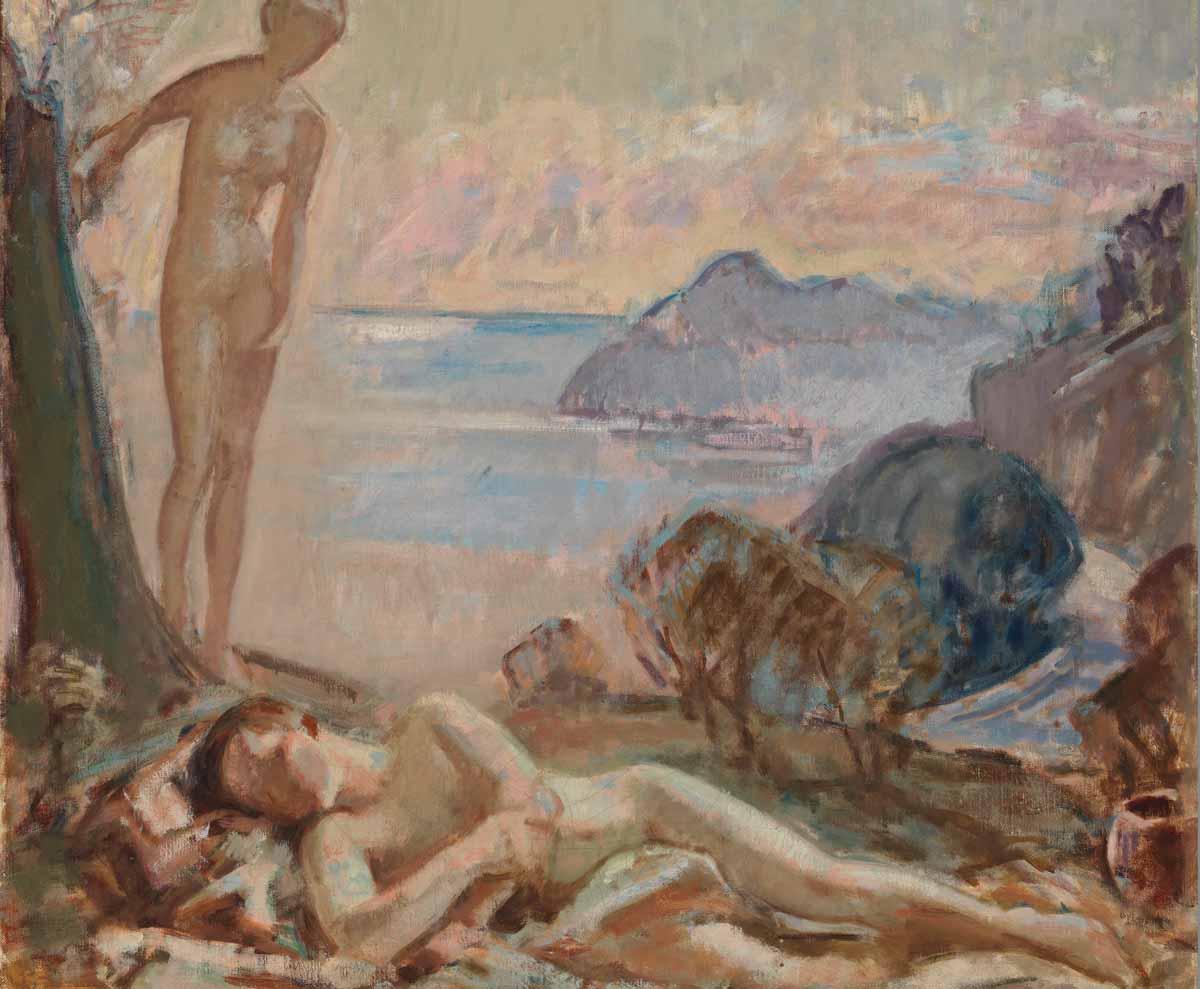

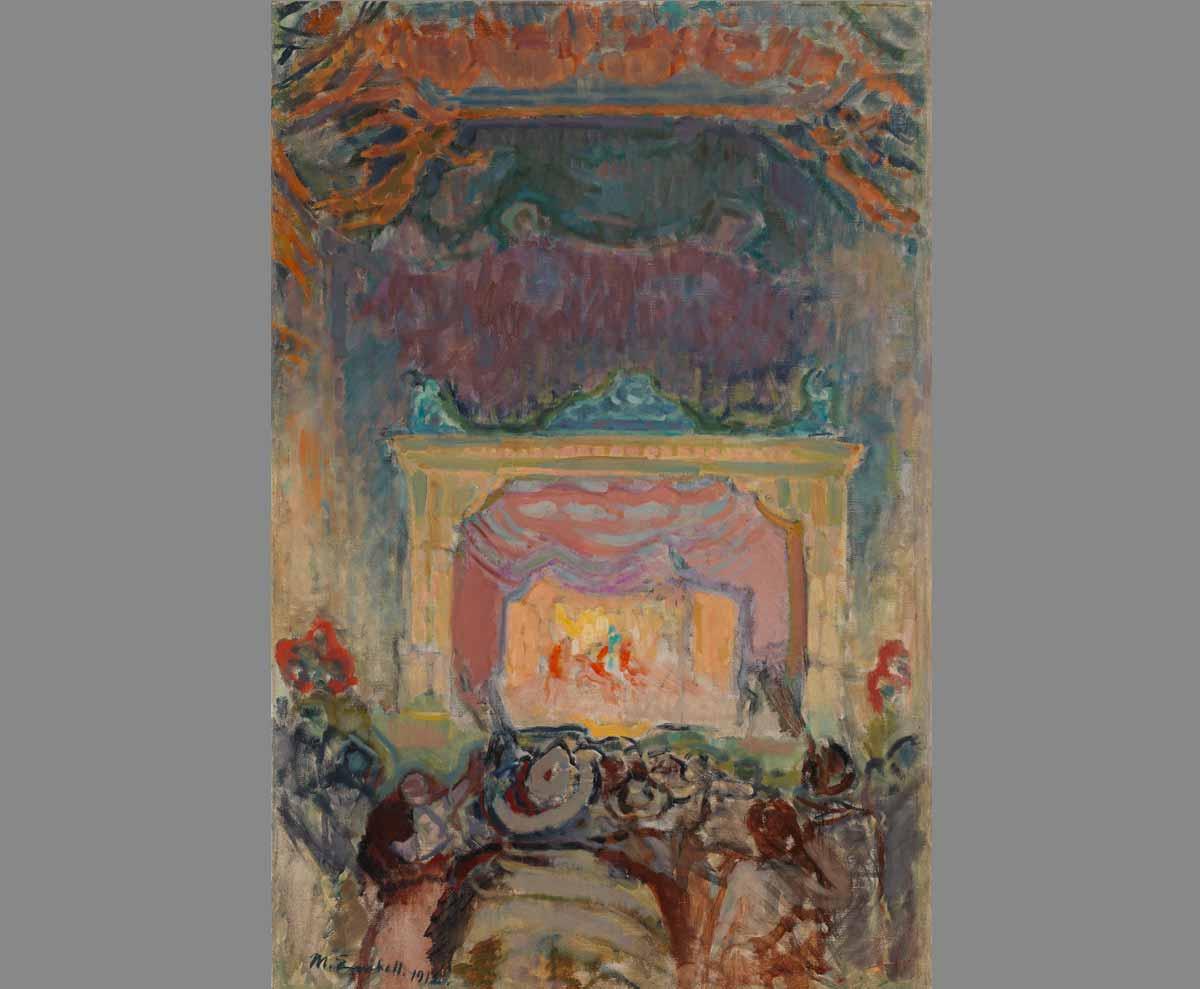

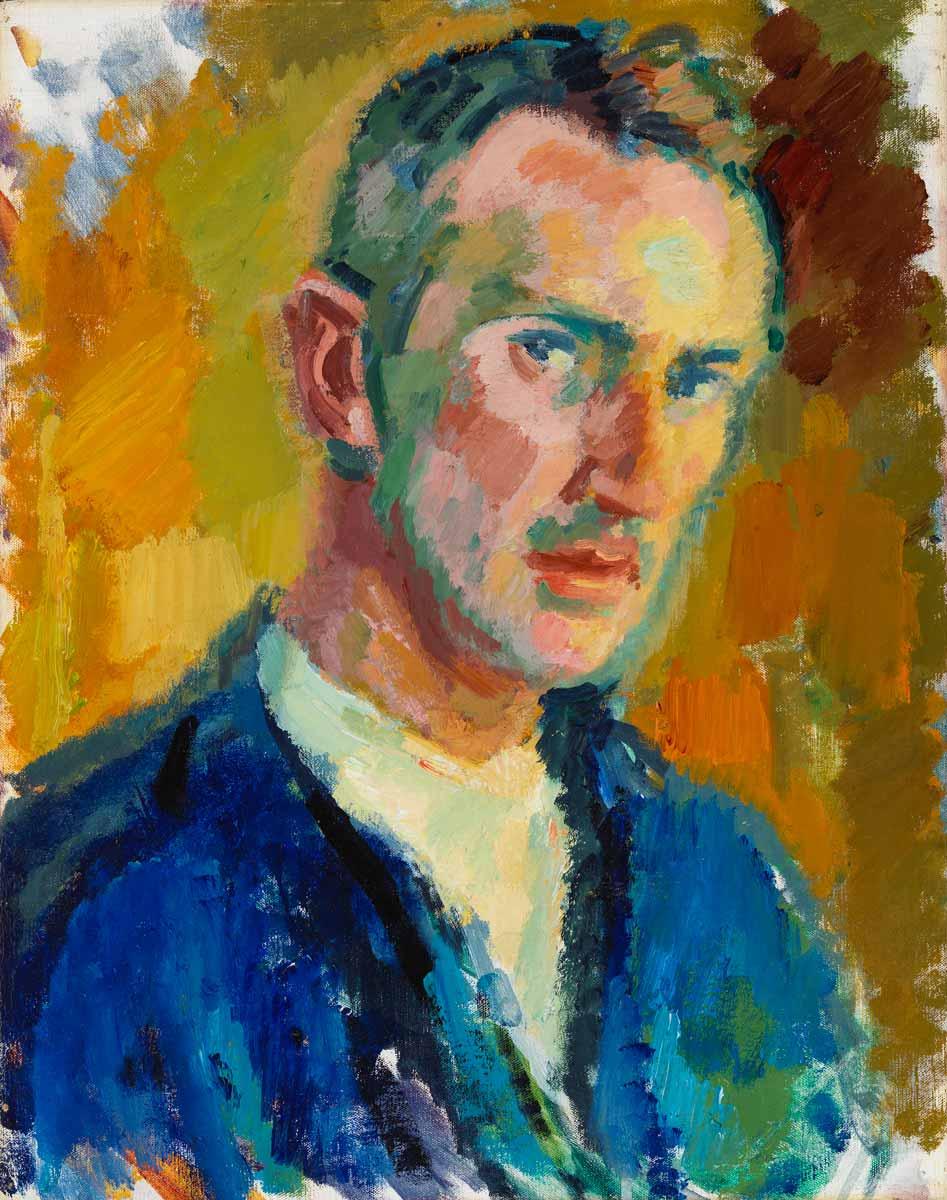

Magnus Enckell’s body of work is strikingly difficult to categorize. Ranging from the sparse to the utterly fantastical, Enckell’s oeuvre does not fall neatly within one aesthetic movement, but instead, offers themes, revisited in new styles. Among his creations, which are now on view in the Magnus Enckell retrospective at Ateneum, one finds a sepia-toned self-portrait; death marching across an austere landscape; and a luminous theatre, painted as if the viewer were deep in the audience, peering over hats and overcoats to catch a glimpse of the stage.

“When we talk about artists, we think that their career is teleological, about going towards something and doing things better and finding yourself,” comments Dr. Marja Sakari, Director of Ateneum, the Finnish National Gallery, and a curator of Magnus Enckell. “But, many artists, they are experimenting, they are doing many things at the same time. It's not a clear continuation.” This is precisely what makes Enckell’s work so interesting.

Little known outside of his home country, Magnus Enckell (1870-1925) is celebrated in Finland for his radical experimentation and influence on Finnish art. During his own time, he had a highly regarded and widely appreciated career and, even after his death, his work was shown in numerous exhibitions in cities like Moscow, Rome, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, and Antwerp. He was a reformer and a traditionalist, a curator and a leader—and, as his current retrospective at Ateneum demonstrates, a diversely talented artist. The retrospective, the first of its scale since Enckell’s self-curated exhibition in 1925, seeks to bring his work back to light on an international stage.

Enckell was born in the coastal town of Hamina, in southeastern Finland, to an upper class family in 1870. His artistic career began relatively early. When he was at school in Porvoo, a teacher encouraged Enckell to reach out to Finland’s most prominent living artist, Albert Edelfelt, due to his precocious talents. Edelfelt took Enckell under his tutelage and, by the age of 19, he was pursuing further study, first at the Finnish Art Society. Finding the environment “so extremely, so incredibly miserable,” Enckell—alongside several students—began taking private lessons with Gunnar Berndtson, who taught them in the French style. After his time with Berndtson, Enckell traveled to Paris to study at the Académie Julian. There, he established what would be a life-long engagement with the latest developments in French painting.