“Good photographs,” Stephen Shore said recently at MoMA, “have visual problems they want to solve. Good pictures are a byproduct; they are not the motive of photography.” This eponymously titled retrospective recounts five decades of attempts to solve photographic problems, with work in nearly every possible photographic medium, encompassing straight black and white, the color snapshot, the picture postcard, the stereograph, and Instagram.

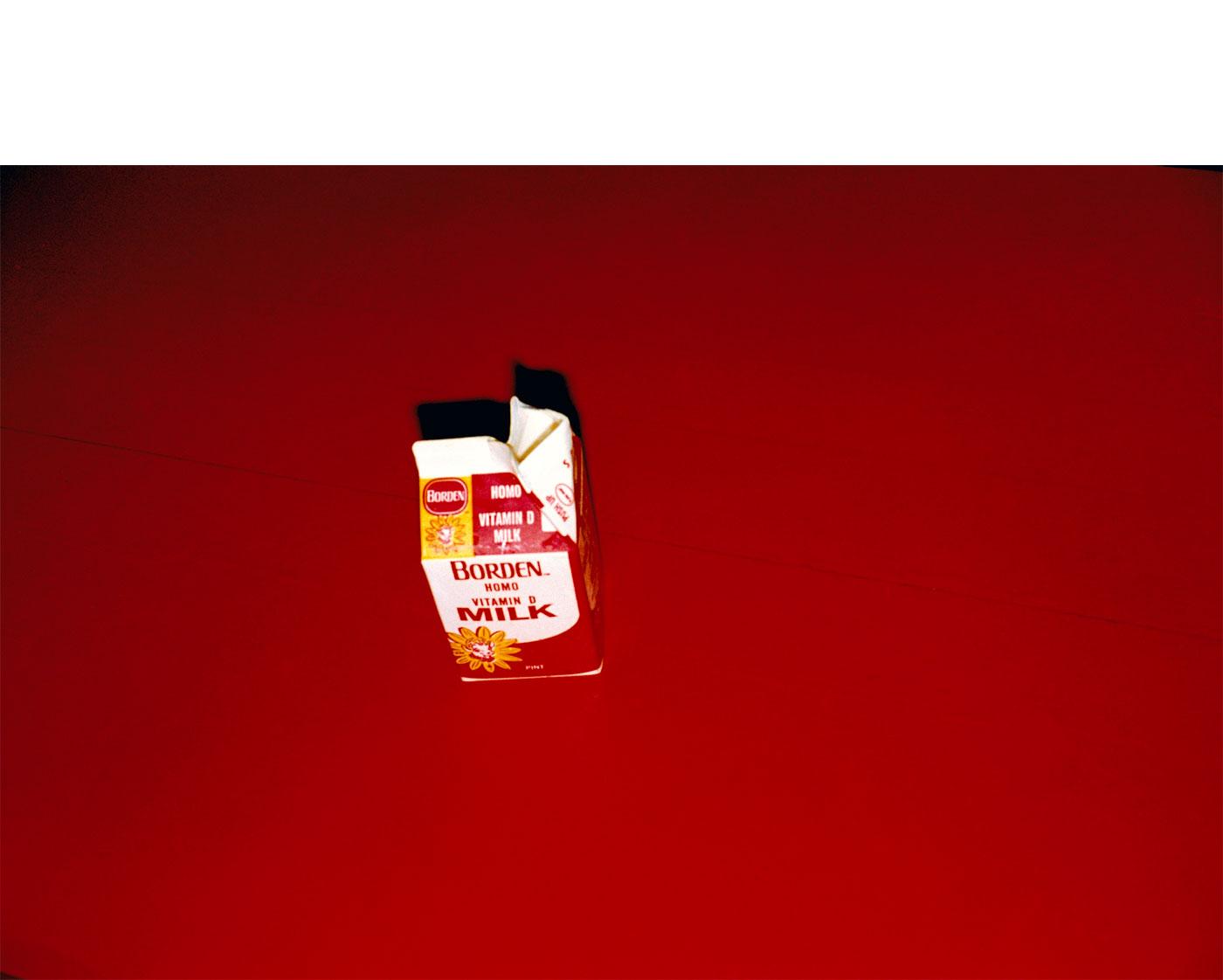

Shore sold his first photographs when he was 14 to Edward Steichen, then MoMA’s curator of photography, in 1962. As a young filmmaker, he met Andy Warhol and subsequently photographed at Warhol’s studio, the Factory, in the mid-1960s. His precocious beginnings lead to his first solo show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art at 23.

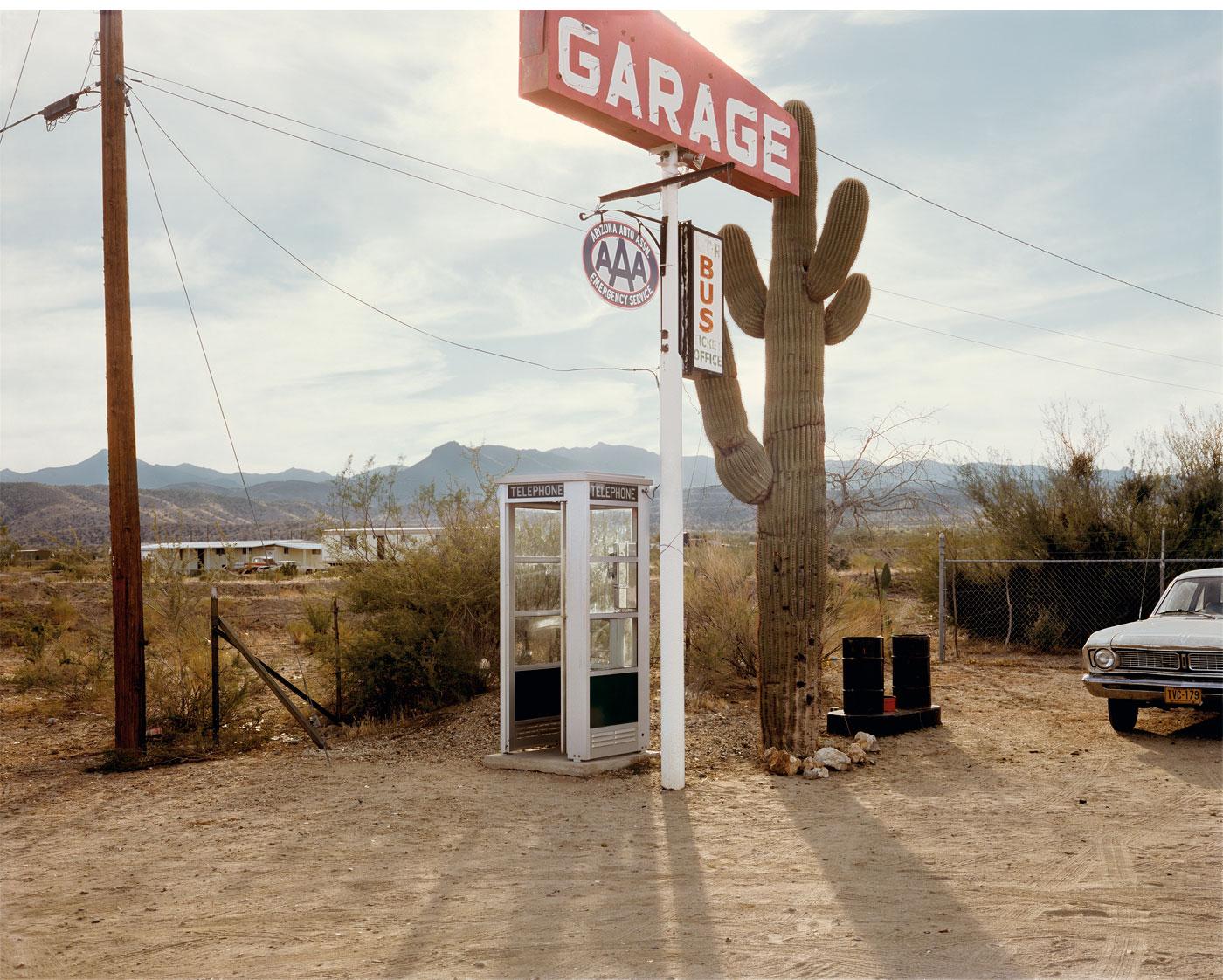

He is best known for his road-trip color photographs, Uncommon Ground, made between 1973 and 1982, which elevated color photography to a fine art. It’s easy to forget, in light of the rise of the Dusseldorf School, particularly Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer and Thomas Struth, how radical the large-format color photograph once was. This show includes some of the most iconic images from that series, but what it does best is capture the omnivorous quality of Shore’s visual concerns.

At key junctures Shore’s work has been embraced as new, often as part of a pivotal curatorial construct. His work was included in the influential New Topographics show in 1975 that also included Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, among others. Shore’s work has also been essential to elaborating the possibilities of the New Color Photography, alongside William Christenberry, William Eggleston, and Joel Meyerowitz.