One of the paramount painters of the twentieth century, Francis Bacon is famous for his scandalous canvases of screaming popes, frightening crucifixions, and twisted faces in his portraits of friends and lovers. Widely collected by major museums and a top seller at auction, the Irish-born Englishman was an obsessive, gifted genius who lived for love and art until he took his last breath at age eighty-two in 1992. His greatest, most puzzling work of all, however, might be the chaotic London studio that he occupied for more than thirty years.

"It was his image machine and where the paintings emerged from, and all the steps leading up to that," said Martin Harrison, editor of Bacon's catalogue raisonné, in a video for the 2009 exhibition A Terrible Beauty, which he co-curated at the Hugh Lane Gallery in Dublin. "It was a very productive mess for him. I mean, he liked it like that."

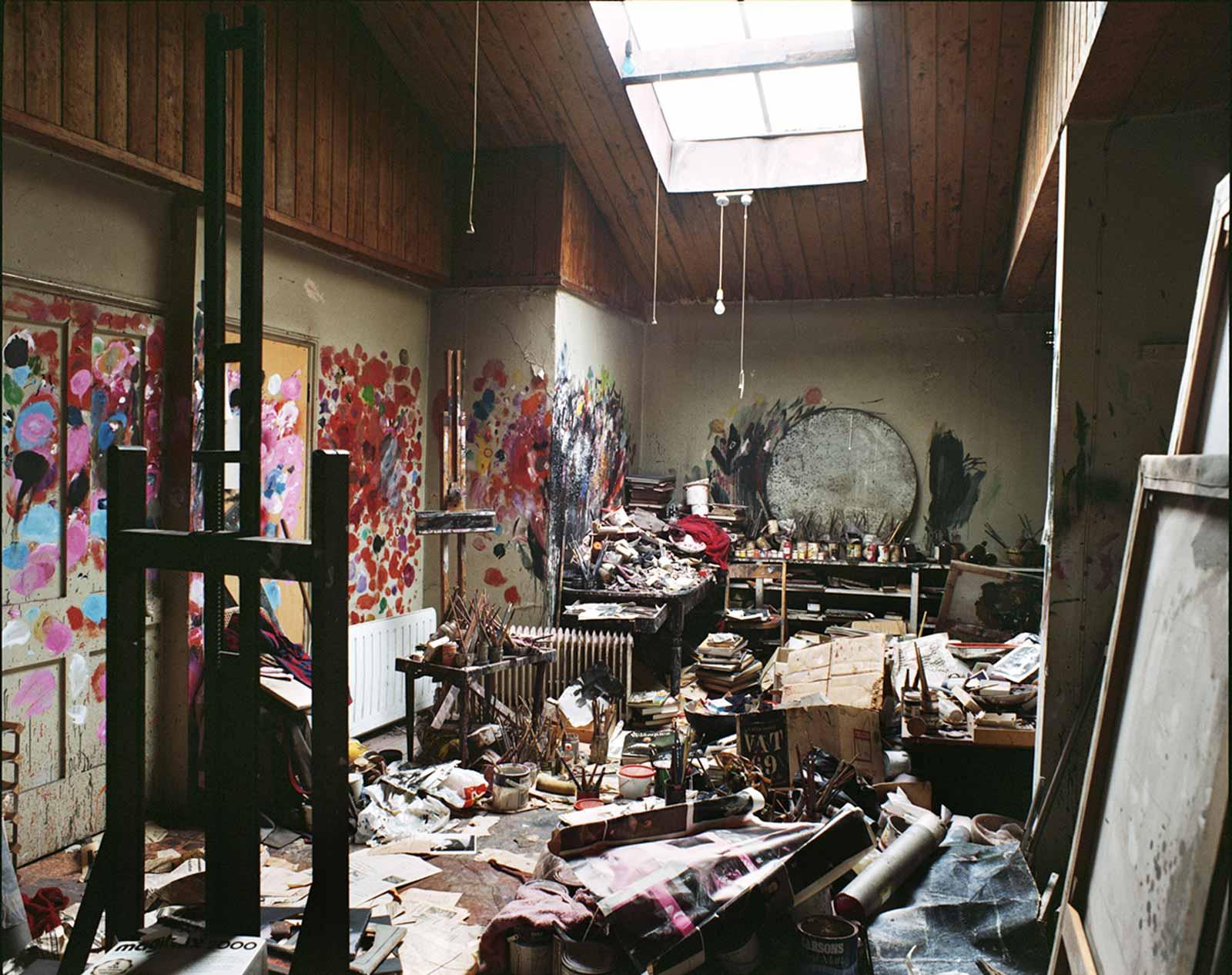

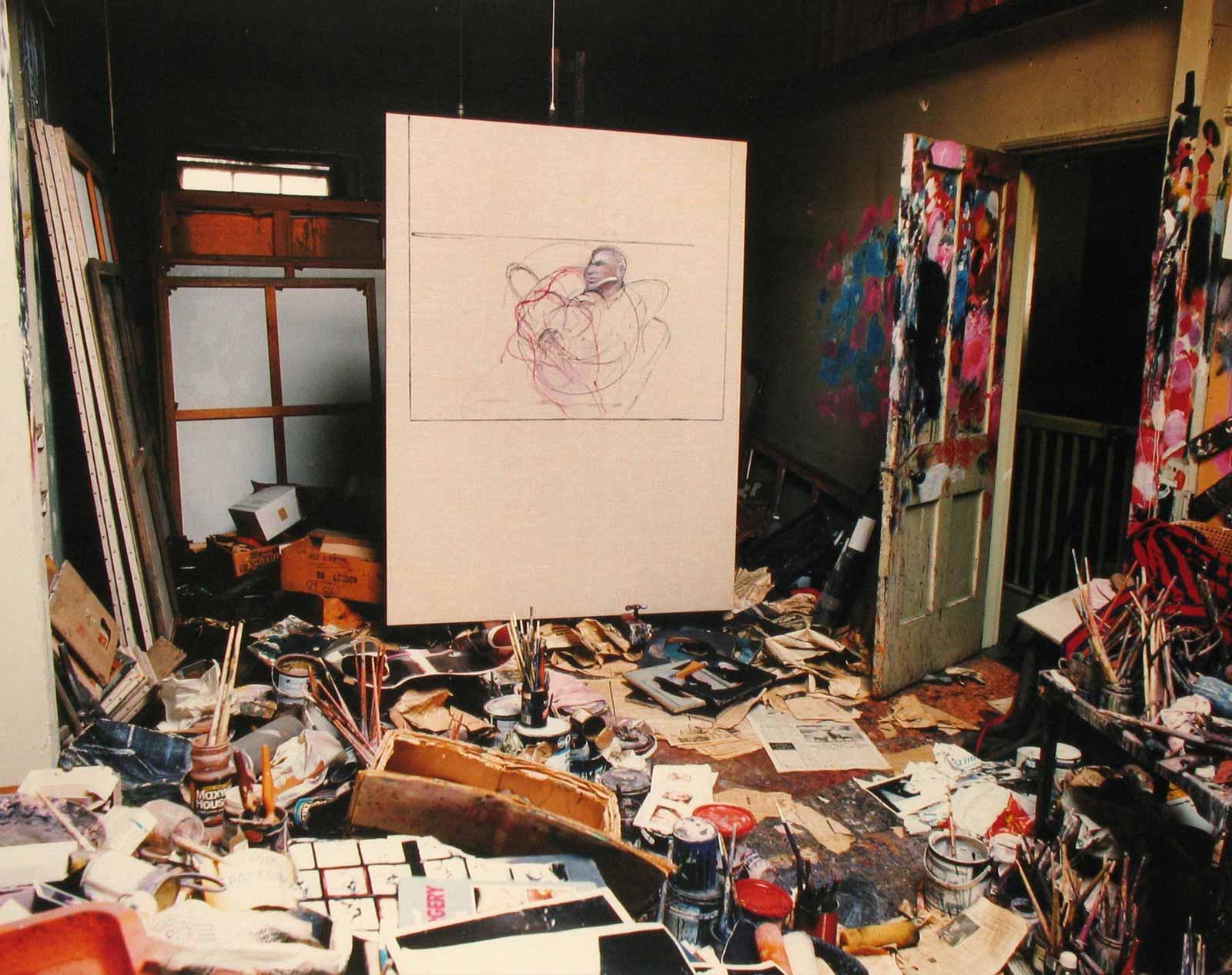

Donated to the Irish museum by the Bacon estate six years after his death, the small, messy studio contained over 7000 items, which have since provided insight into the enigmatic artist's unique working method. Cataloged by a team of archeologists, conservators, and curators before being shipped to Dublin for reconstruction, the studio held a couple of thousand art supplies, hundreds of books and catalogues, 1500 photographs, more than 1000 images torn from magazines, 100 slashed canvases, 70 drawings, and loads of empty champagne cartons piled in the corner of the room.

Recalling her first viewing of Bacon's studio at 7 Reece Mews in the South Kensington neighborhood of London some years later, Hugh Lane Gallery director Barbara Dawson said, "It was like walking into the artist's head—books and papers and photographs strewn about the floor, slashed canvases on the shelves, all of these paintbrushes—a latter-day Egyptian tomb, in a way."

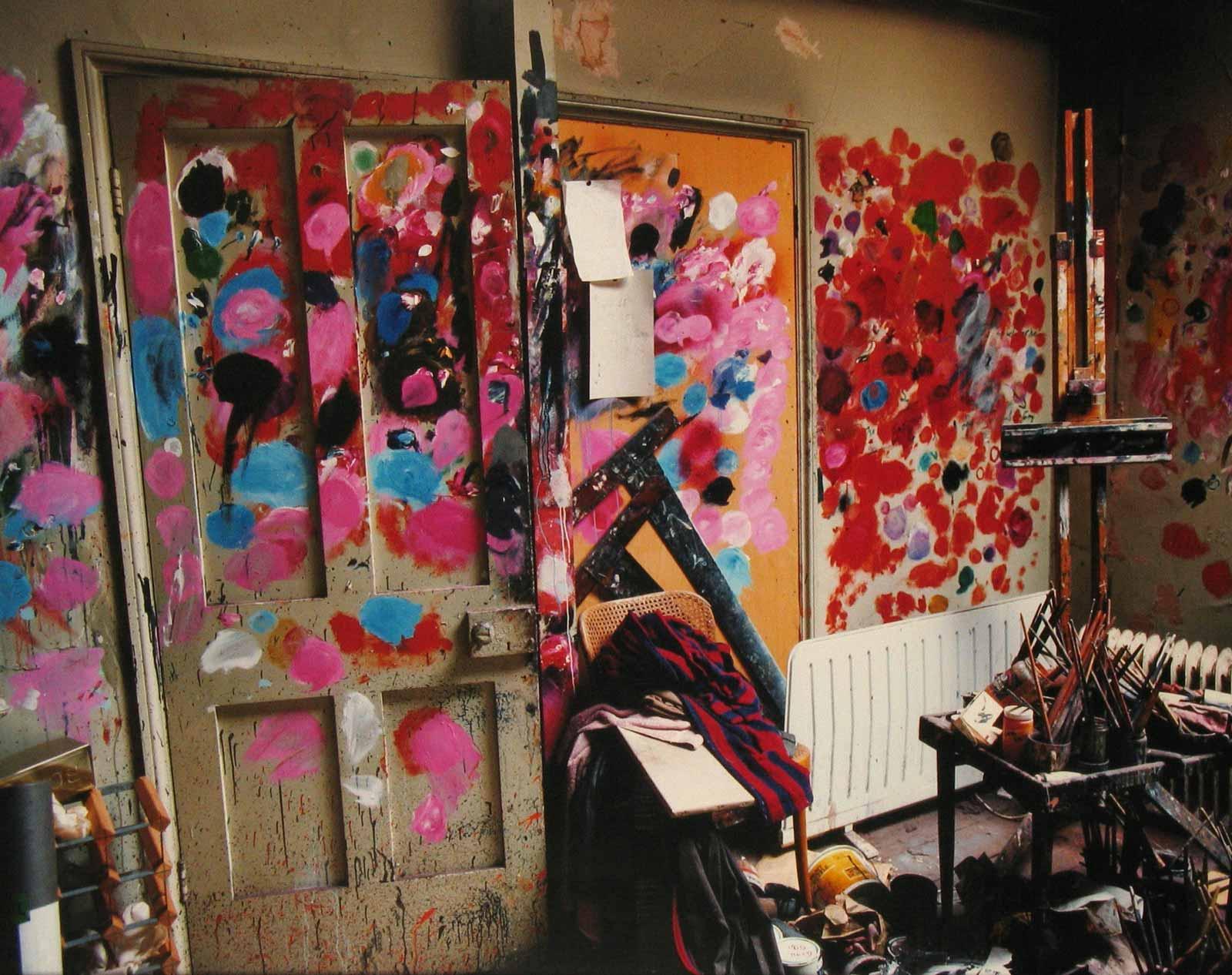

Bacon worked in the studio, which had once been the hayloft of a stable for a coach house, but he never organized it—instead it evolved around him. He used the door and walls to mix his colors and left trails of paint across the ceiling when throwing it on his canvases. When working, he positioned himself under the skylight with his painting supplies to his right, photographic source materials on the floor to his left, and the easel in front of him. While painting, he faced a round pitted mirror, which made the space seem larger and afforded a reflected image of the artist at work—his only studio companion.

"I've been here for years—about twenty-three or more," Bacon told ITV's The South Bank Show host Melvyn Bragg, when he visited the studio in 1985. "It's kind of a dump that nobody else would want, but I can work here. These are a few of my abstract pictures here [pointing to the splotches of paint on the door and surrounding walls] because I use the walls and things to test the colors out on. I've tried to clean it up, but I work much better in chaos. I couldn't work if it was a beautifully tidy studio. It would be absolutely impossible for me. Chaos, for me, breeds images."