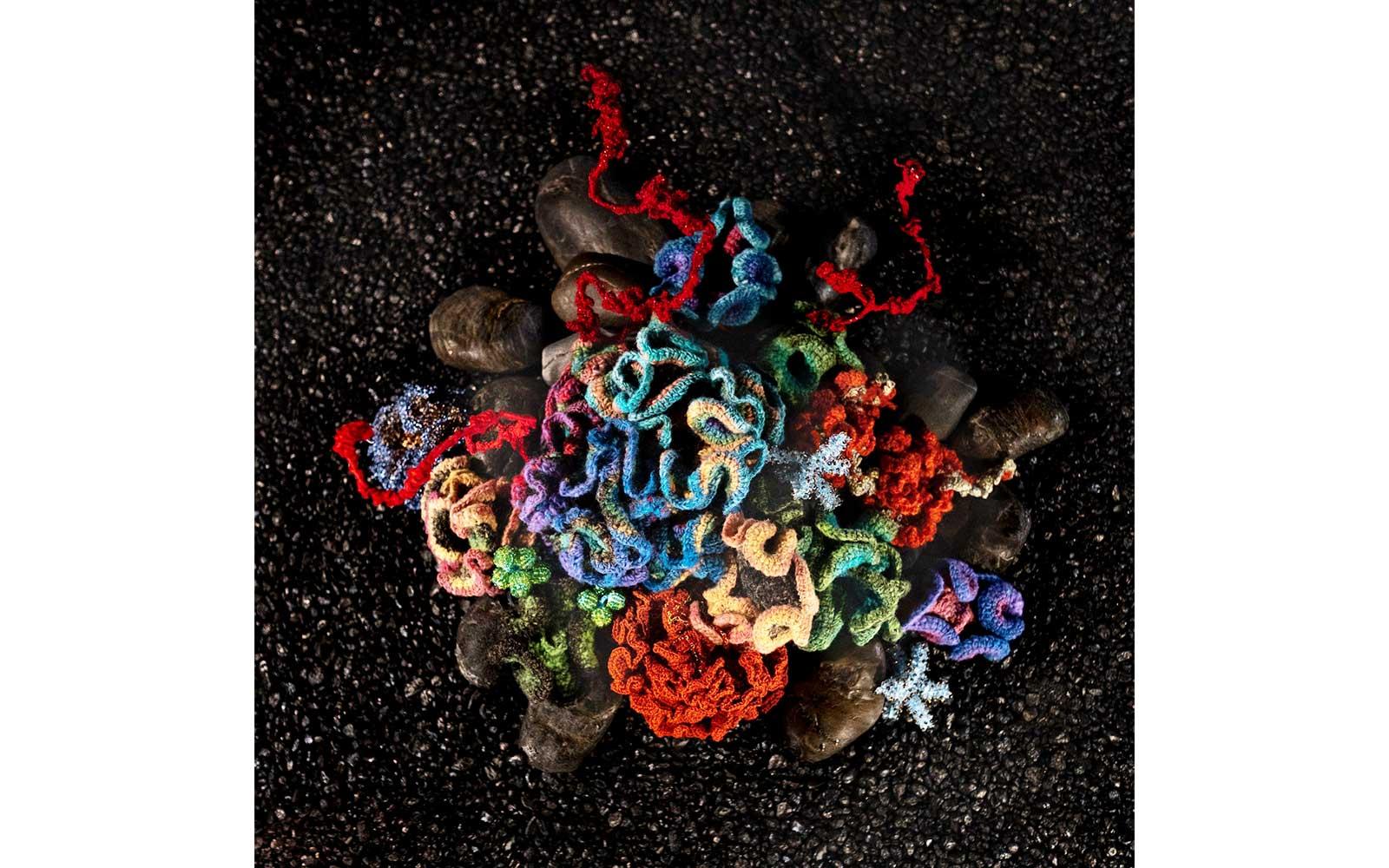

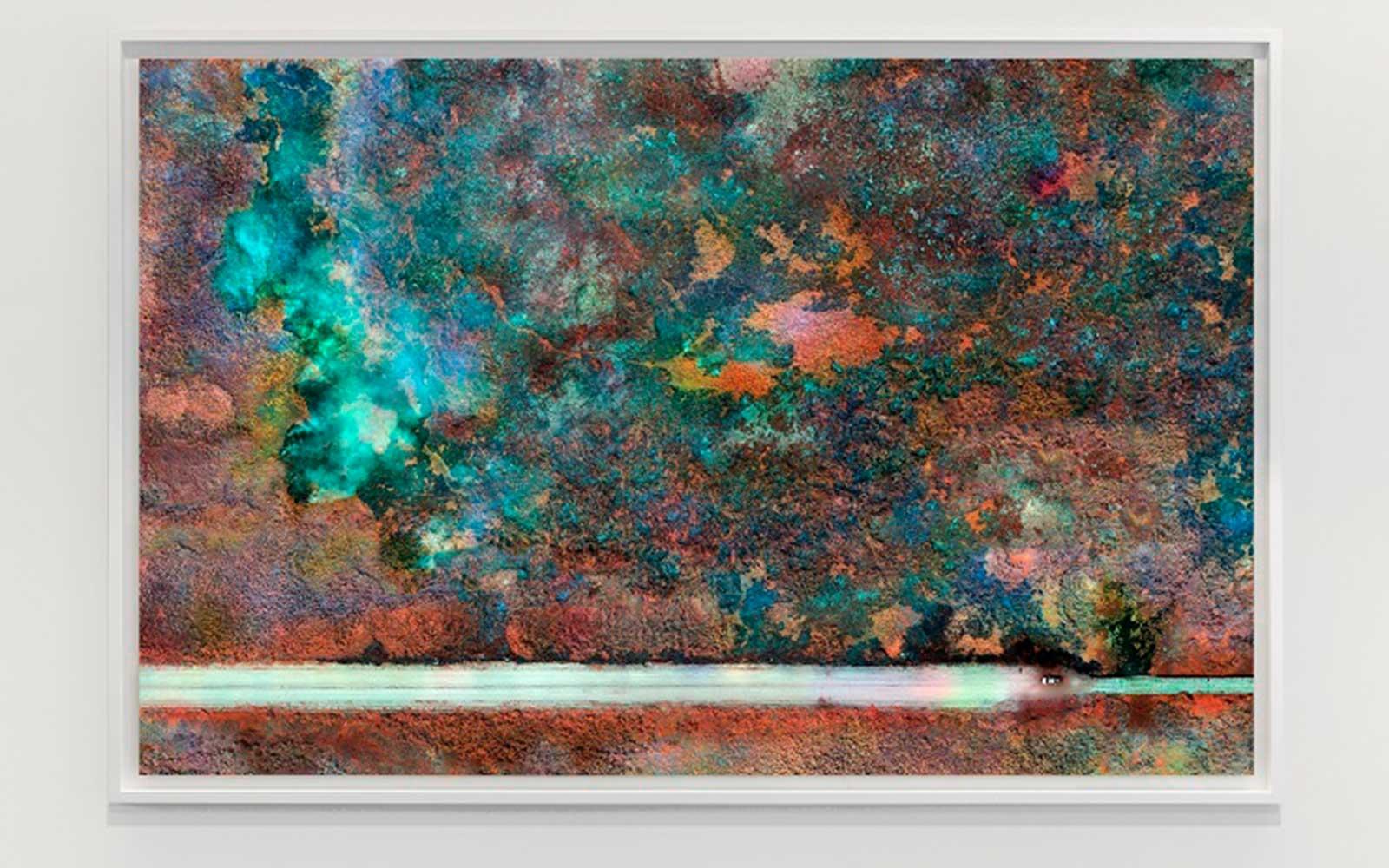

Headquartered in Dorset, England, Cape Farewell has been devoted to shifting perceptions about climate change since 2001, with founder and international director David Buckland at the helm. As climate warnings went unheard, Buckland was inspired to reunite the creative fields of science and art to converse with people using a cultural language. “Art always seduces. And people love being seduced,” he points out. “Everybody holds a piece of art in their psyche…. So art is a very powerful weapon.”

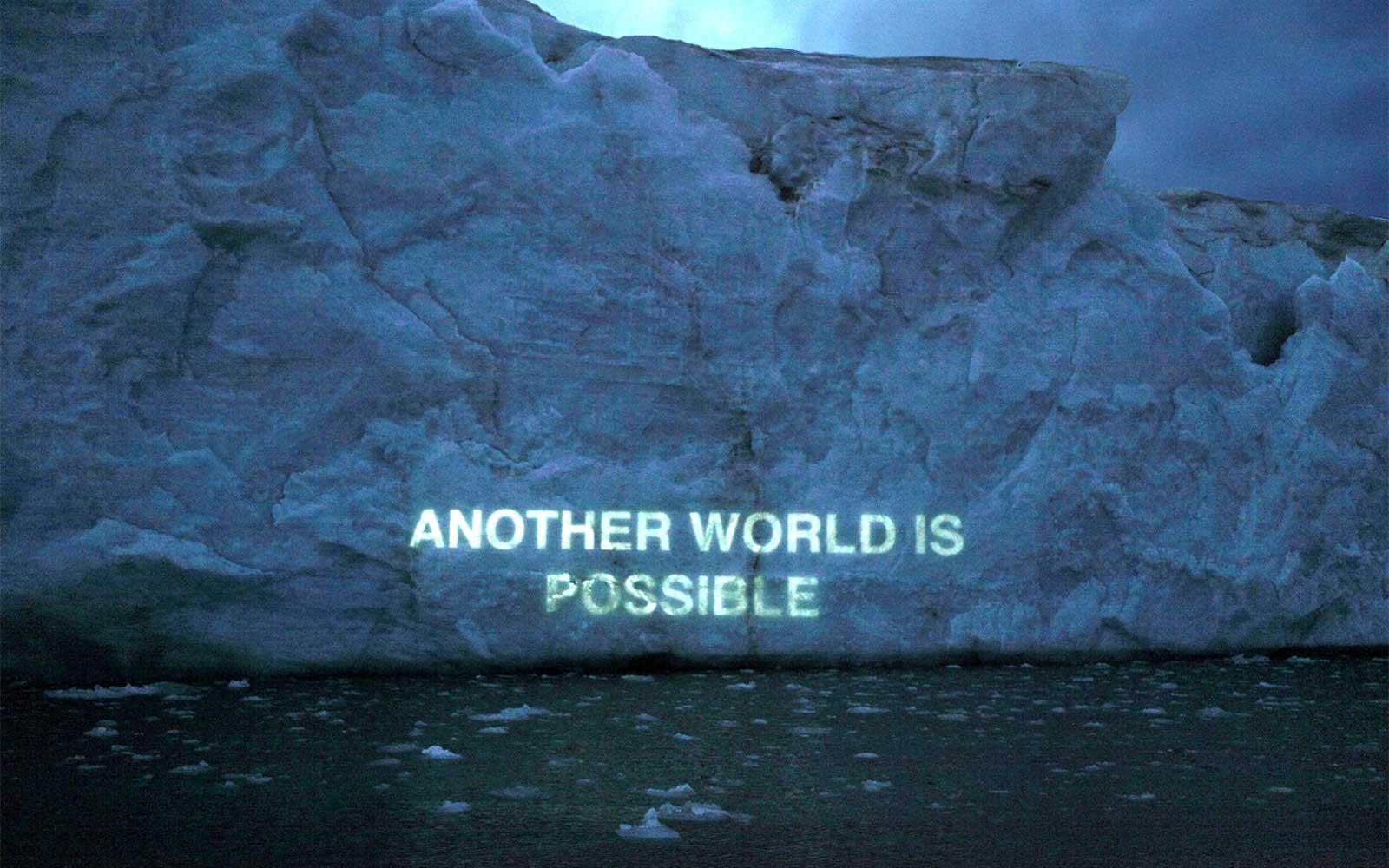

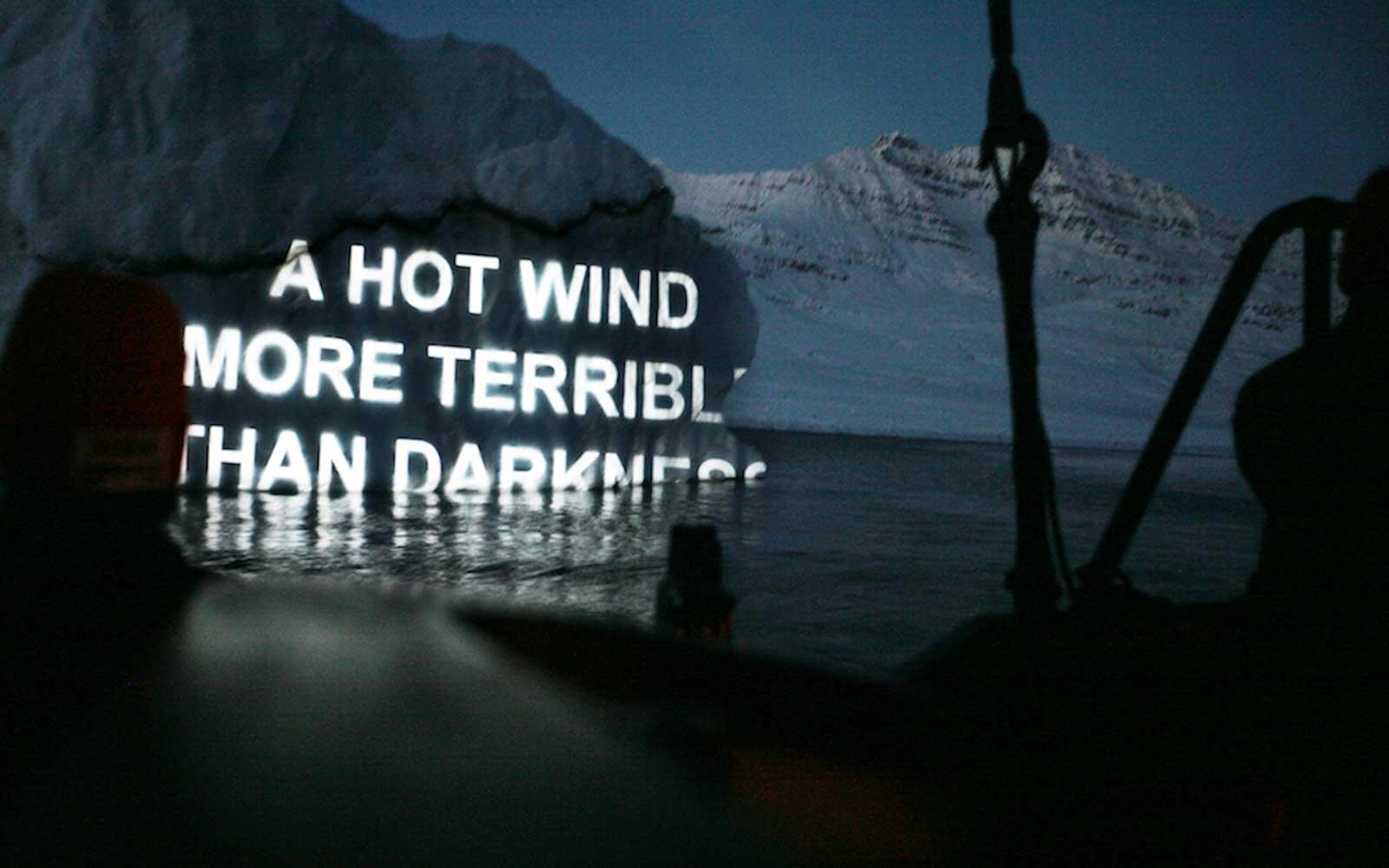

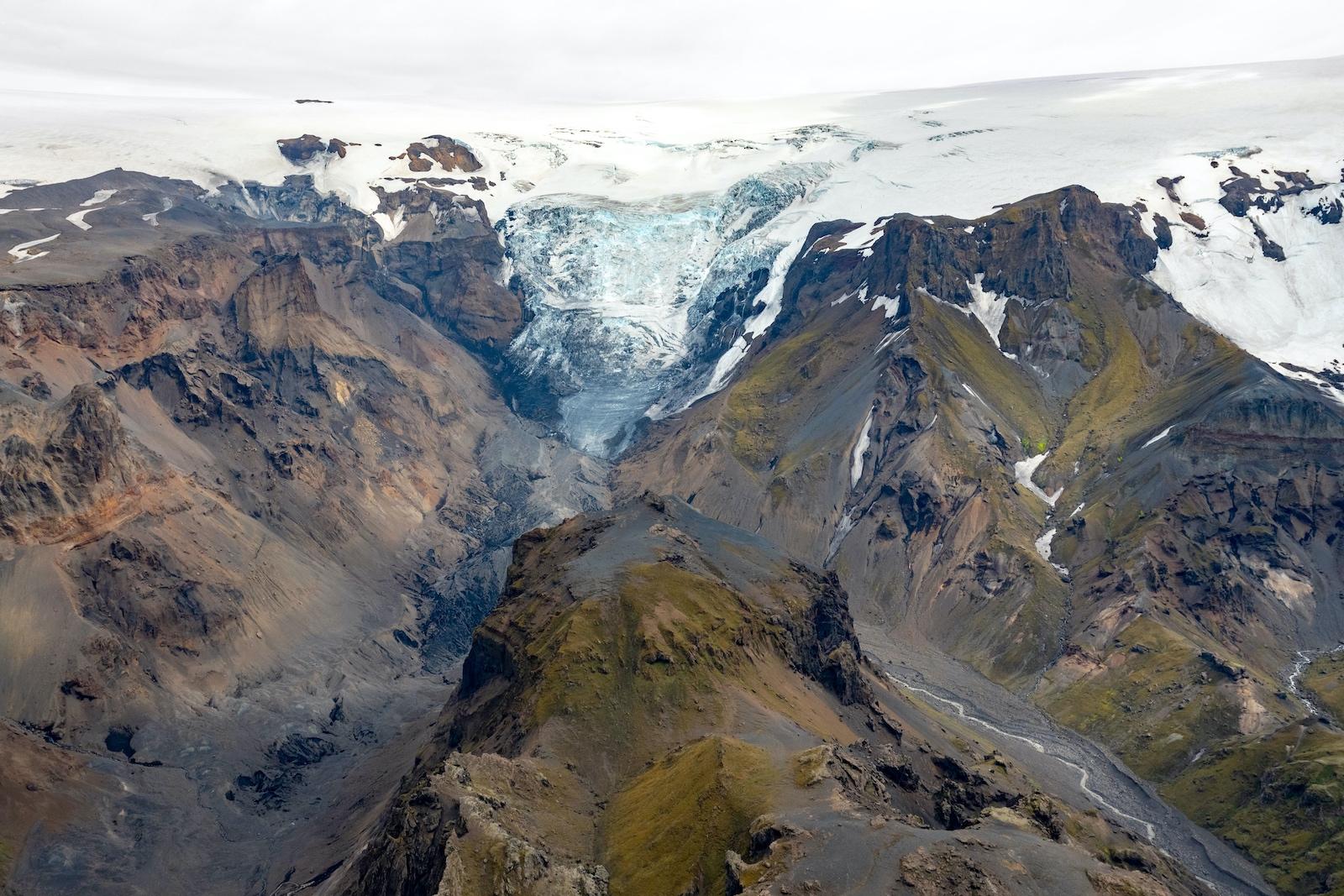

Also an artist, designer, and filmmaker, Buckland considers the High Artic the best place to witness “big physical” climate changes. Describing his first trip there, he refers to the bleak, dramatic landscape as having “layers of magic that you can’t imagine…until you experience them.”

Cape Farewell’s 2008 expedition to Disko Bay on the west coast of Greenland was documented in their film Burning Ice. Scientists participated with a variety of creatives, including musician KT Tunstall, poet and playwright Lemn Sissay, and the icon Laurie Anderson.