The hit Showtime television series, The Tudors, that aired from 2007-2010 may have created some sense of familiarity with the characters who brought to life the historical period overlapping the Italian High Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation–but don’t depend on this TV series for the facts. As executive producer Michael Hirst said, "Showtime commissioned me to write an entertainment, a soap opera, and not history. … And we wanted people to watch it.”

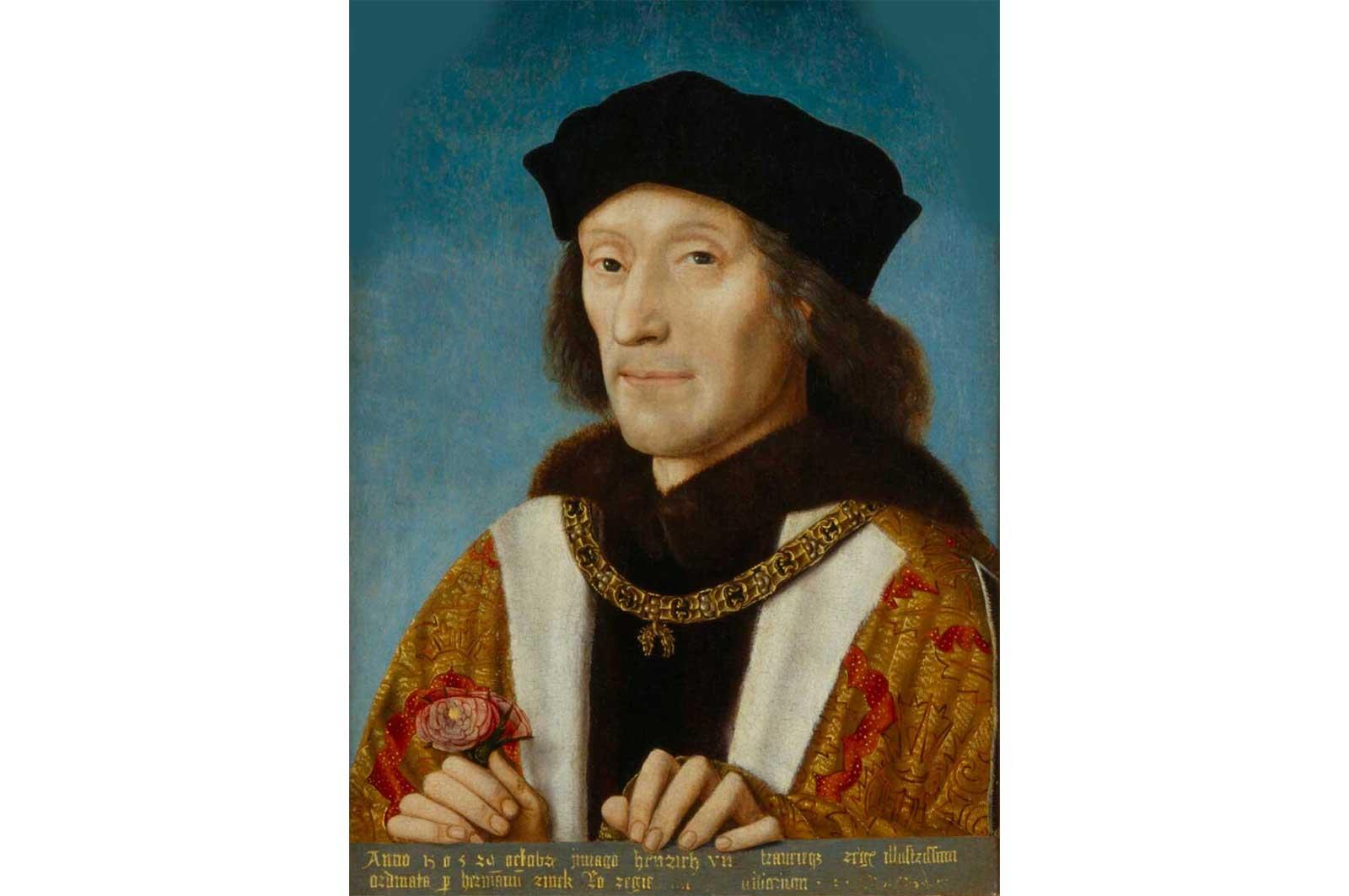

The Tudors: Art and Majesty in Renaissance England currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art will go far to set the record straight. Here, the story of 16th century England is told through the lens of the artwork and craftsmanship fueled by the influential Tudor royal dynasty, rather than the sexual exploits, multiple marriages, and beheadings under the reign of King Henry VIII that were the focus of the TV series. The House of Tudor, beginning in 1485 with the assent of Henry VII to the throne, ended in 1603 with the death of his granddaughter, Elizabeth I. It heralded the end of civil war, known as the War of the Roses that had been fought for control of the Kingdom of England. The Tudor Rose, Henry VII’s clever melding of a red and white rose joining symbols from two antagonistic political factions, the families of Lancaster and York, became in effect a logo for the Tudor dynasty. It appeared like a Good Housekeeping seal of approval in everything from paintings to engravings, textiles, and architecture.

Surprisingly, this is the first American exhibition to present Tudor artistic influence on English cultural heritage. Conceived and organized by Elizabeth Cleland, Curator in the Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts and Adam Eaker, Associate Curator of European Paintings, the exhibition features over 100 objects, going beyond iconic painted portraits to embrace sculpture, tapestries, manuscripts, and armor creating a picture of the thriving world inhabited by the international group of artists and craftsmen supported by Tudor patronage. The audio guide for the exhibition has incorporated first-hand accounts extracted from original documents using the actual words of the same colorful characters made familiar through books of historical fiction, plays, and the aforementioned TV series.