The story of the Trojan War has been a source of fascination and historical revision since ancient times. “It is questionable whether we can have complete confidence in Homer’s figures, which, since he was a poet, were probably exaggerated.” So reasoned the Greek historian Thucydides, writing at the end of the 5th century BC, who downplayed the number of combatants who were said to have taken part in the Trojan War in order to demonstrate the unrivaled magnitude of the great war of his own day.

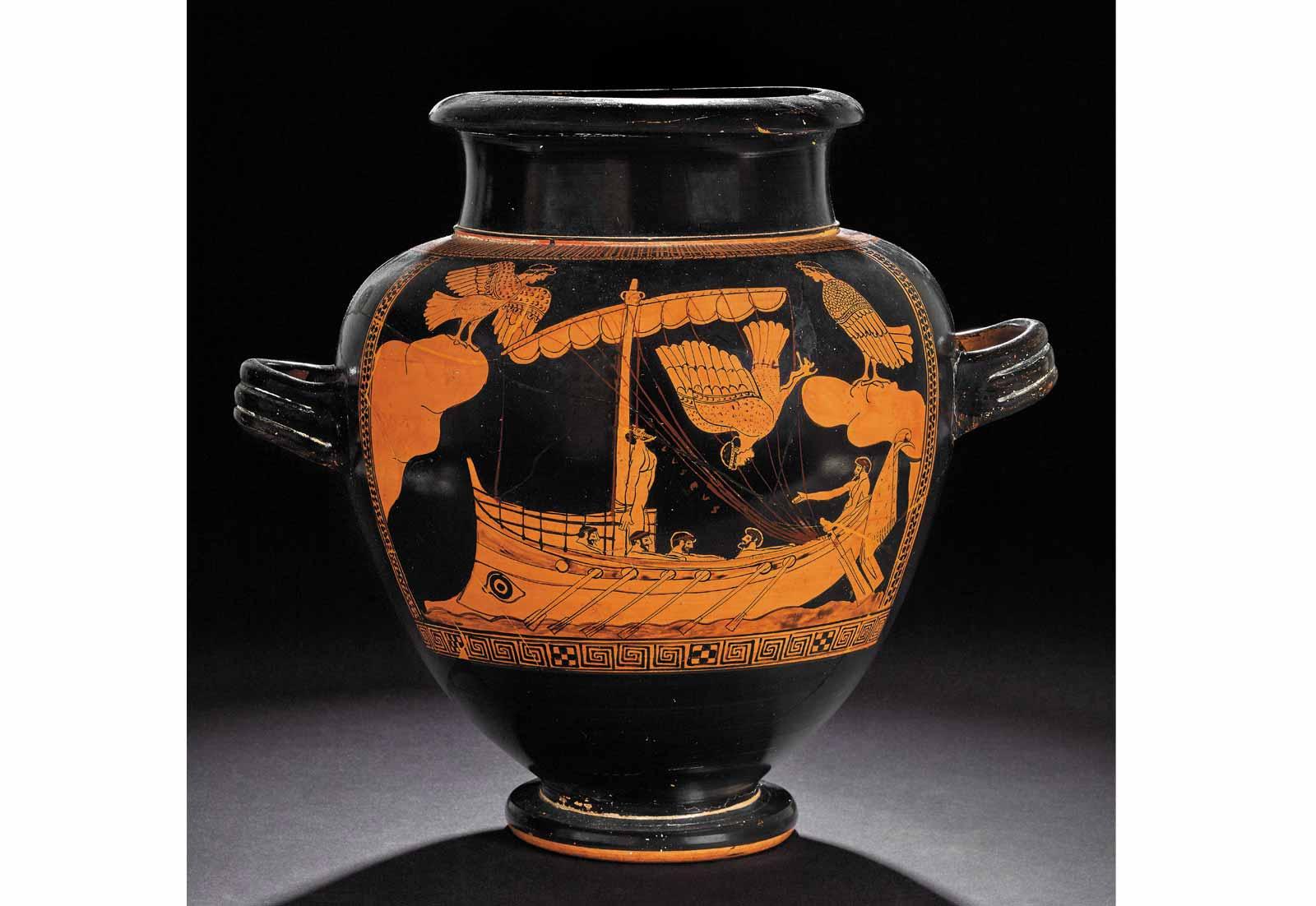

A generation earlier, the historian Herodotus had also questioned the account of the siege of Troy as told by Homer, the presumed author of the Iliad and Odyssey. Herodotus is inclined to accept an alternative version where Helen–the beautiful queen whose escape with, or abduction by, her lover Paris started the hostilities–never actually arrived in Troy. Instead, after her ship was blown off course, Helen landed in Egypt where she then sat out the ten-year war. Herodotus’ reasoning is that Helen could not have been in Troy because surely King Priam, Paris’ father, would have handed her back to the Greek expeditionary force once they laid siege to his city, rather than endanger his entire people over the actions of his son.

It is not simply that there are plot holes in the story of the Trojan War that necessitate such rationalizations–the legend itself and the history of its transmission encourages alternative versions. A new exhibition at the British Museum, Troy: Myth and Reality, explores how the epic has been retold and reinterpreted over three millennia.

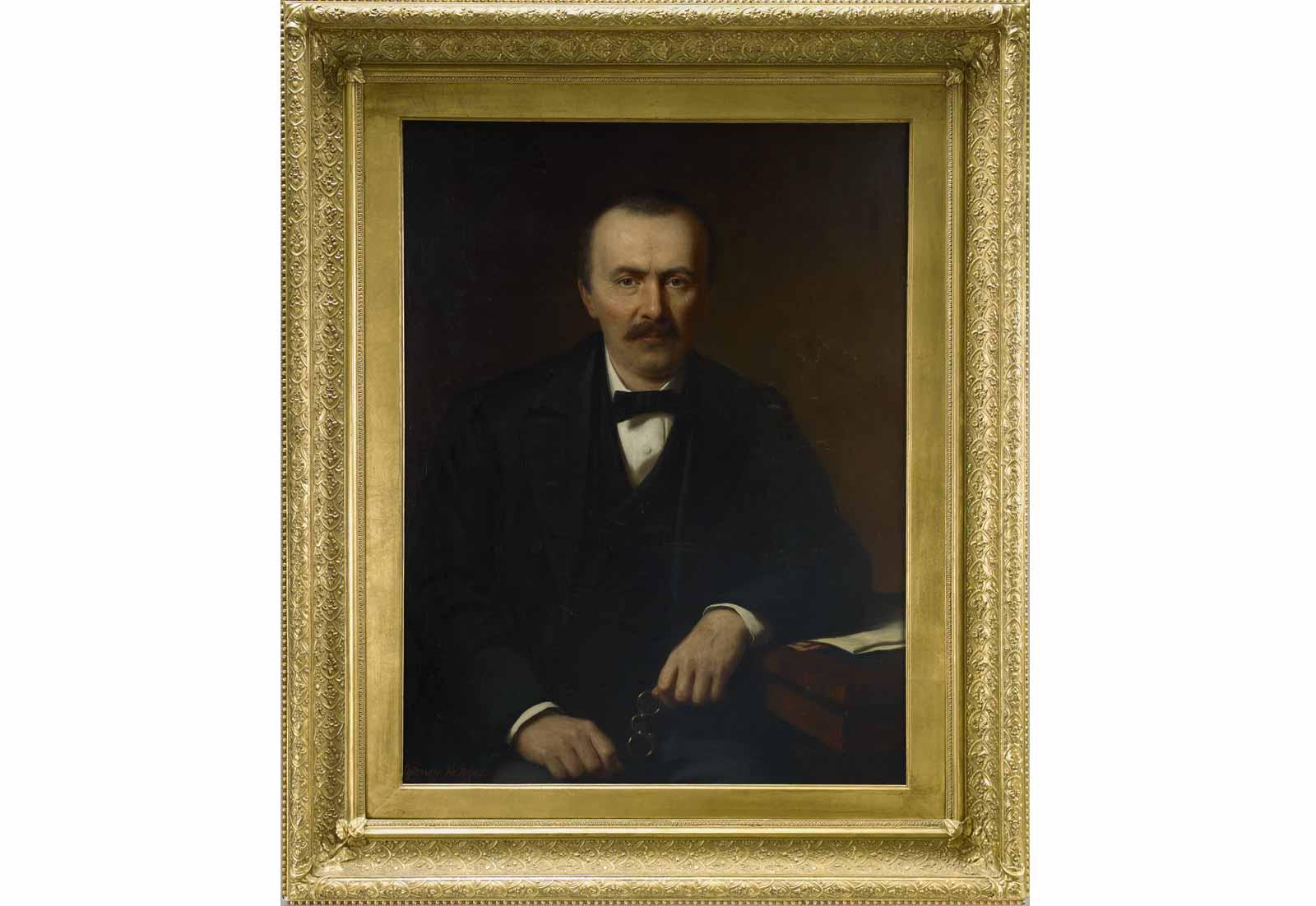

Asked why the British Museum has chosen now to put on an exhibition about Troy, Alexandra Villing and Victoria Donnellan, two of the curators, reply “why not before?”–after all, it has been 140 years since the last major show on Troy in the United Kingdom. As they point out, the story has an enduring fascination due to its “compelling characters and universal themes of human experience,” through the subjects of “love, loss, and war it emphasizes the consequences of individuals’ actions and decisions.”

That the stories of the Trojan War can be given new relevance and meaning in different ages and contexts is evident throughout the show. In his vibrant 1970s collages, Romare Bearden transplants Odysseus’ adventures to landscapes that resemble Caribbean islands. On video, a performance of Queens of Syria is shown. Acted by women refugees of the ongoing conflict in Syria, the play adapts material from Euripides’ 415 BC tragedy Trojan Women, which explored the fate of civilians caught up in war. Indeed, the curators are keen to emphasize how the last few decades have seen an assertive repositioning of the role of women in the narrative of Troy. Emblematic of this is Eleanor Antin’s 2007 photographic print based on Rubens’ Judgement of Paris, with the figure of Helen–absent from the Old Master’s 1638 painting–now present.