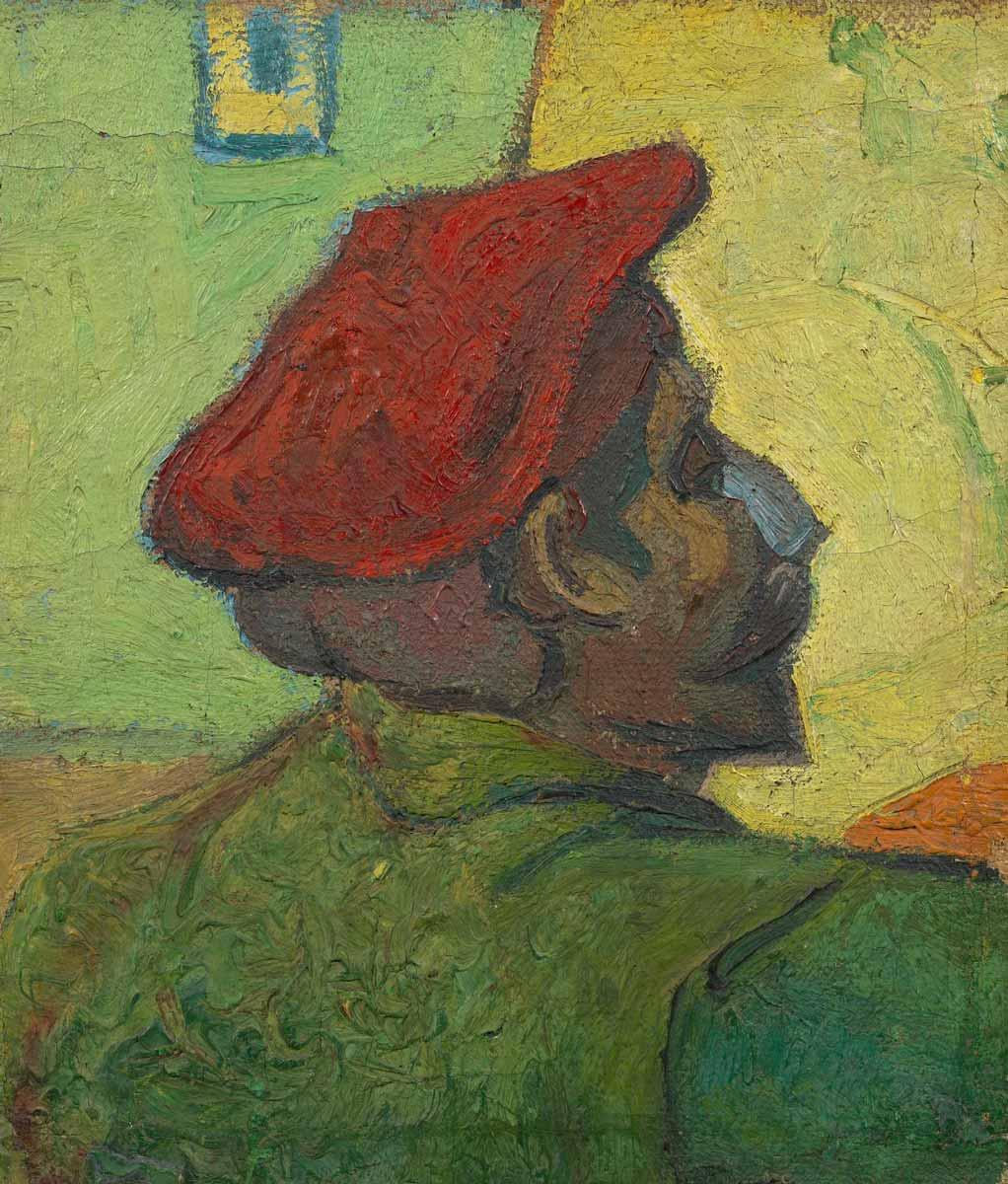

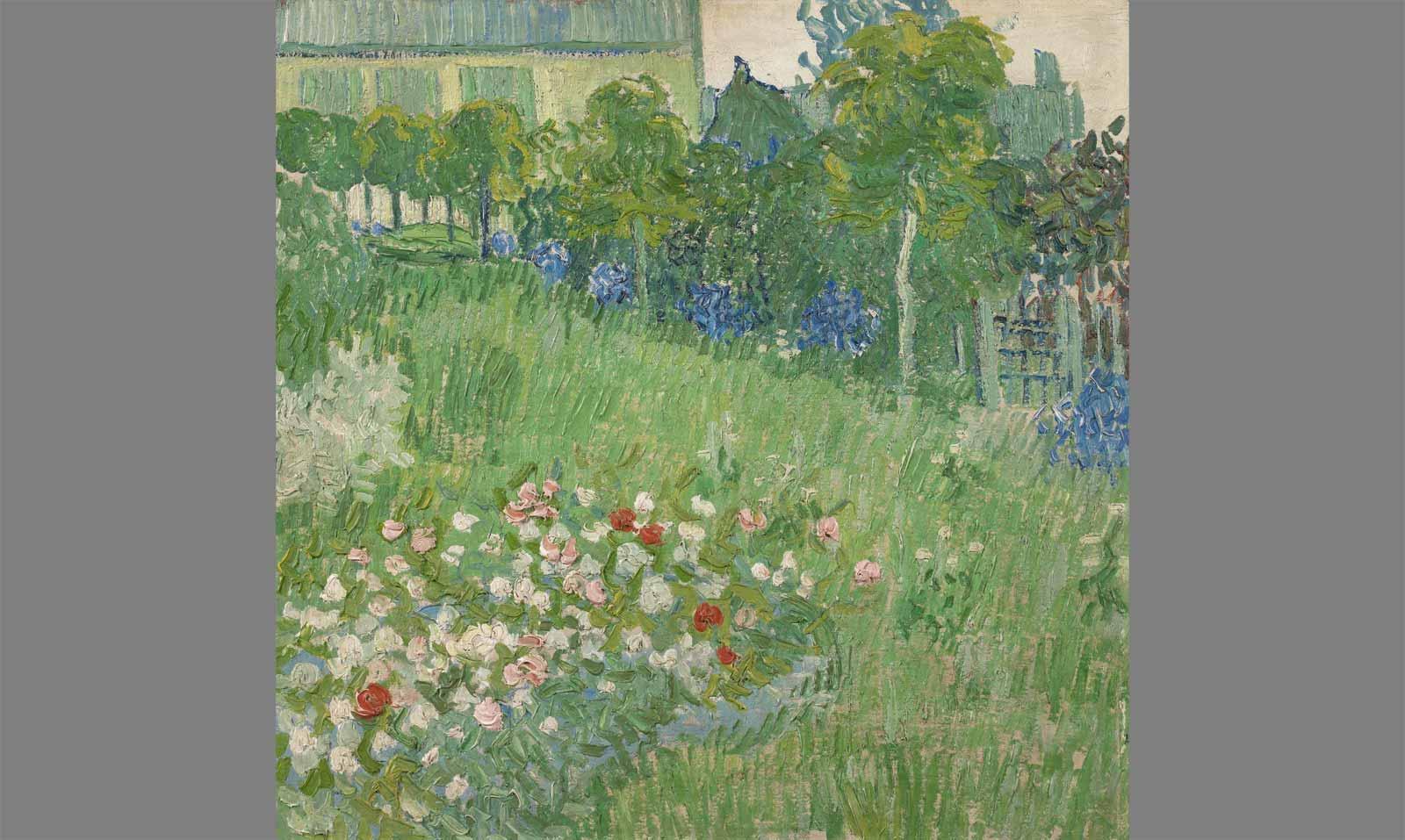

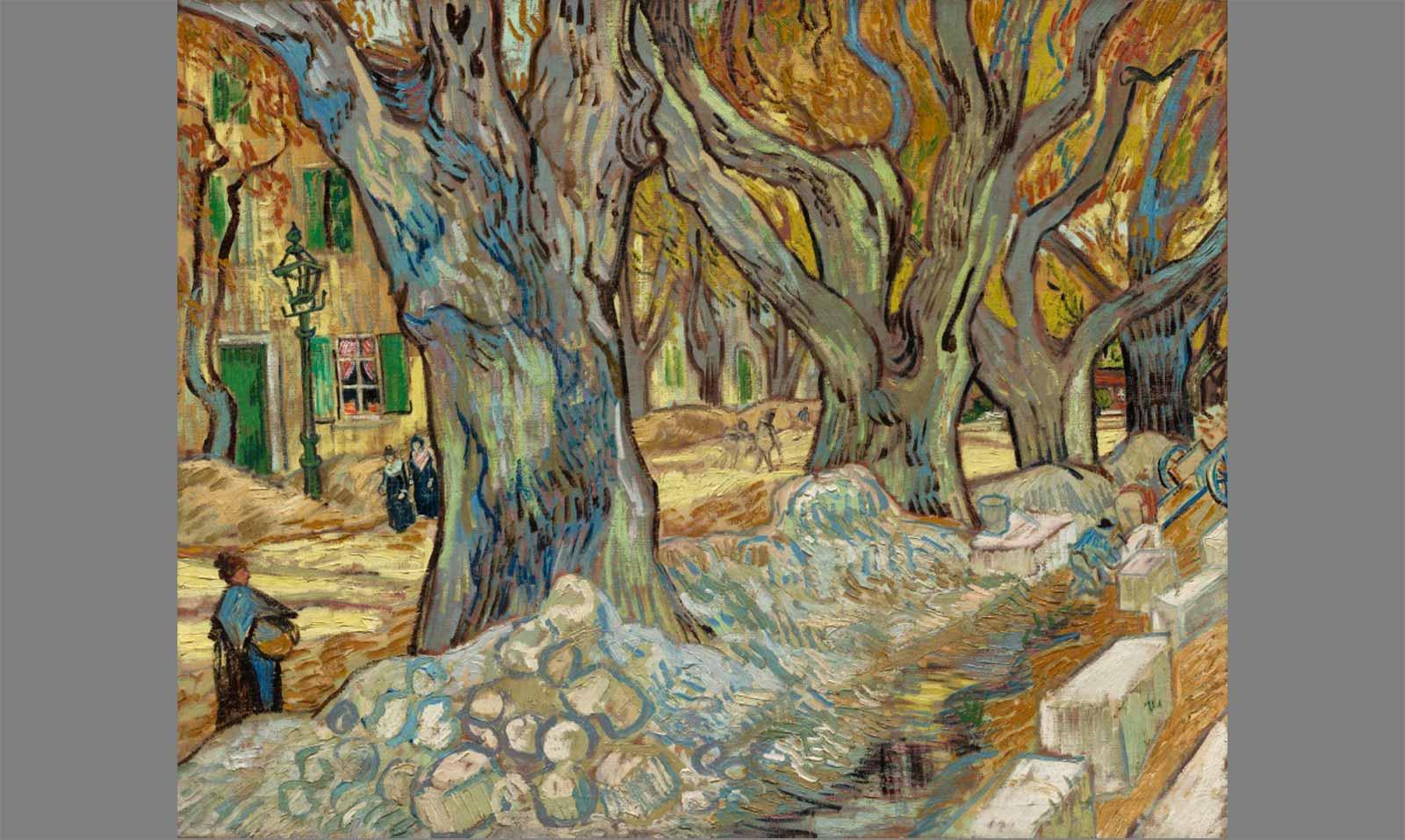

There were no artist supply shops at the mental health asylum in Saint Rémy-de-Provence, and the care package of canvases that Vincent van Gogh’s brother, Theo, mailed him from Paris hadn’t arrived yet. Van Gogh’s favorite surface to paint on was a type of canvas from the Parisian firm of Tasset & Lhote, but there was none to be found at the psychiatric hospital that was the artist’s address for most of 1889 (where he committed himself after famously slicing off part of his ear). Left with no choice and a feverish desire to paint, he improvised.

“In our museum we found torchon [tea towel] in a painting,” Louis van Tilborgh, senior researcher at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, told Art & Object. “It’s clear that it’s simply about the question of: what do you do when you don’t have the material that you want to use, normally? Well, then you choose other stuff. And it’s possible to choose, indeed, something like this torchon.”

The torchons likely came from the asylum kitchen, and Van Gogh used them in a small handful of paintings in late 1889 and mid-1890. The artist stretched the cloths on wooden frames and primed them just as he would any linen canvas, but a pattern of red rectangles is still visible in some areas where the artist applied paint more thinly. The following year, when he was a guest at the Auberge Ravoux in Auvers-sur-Oise, he painted on kitchen towels again–probably borrowed from the innkeeper.