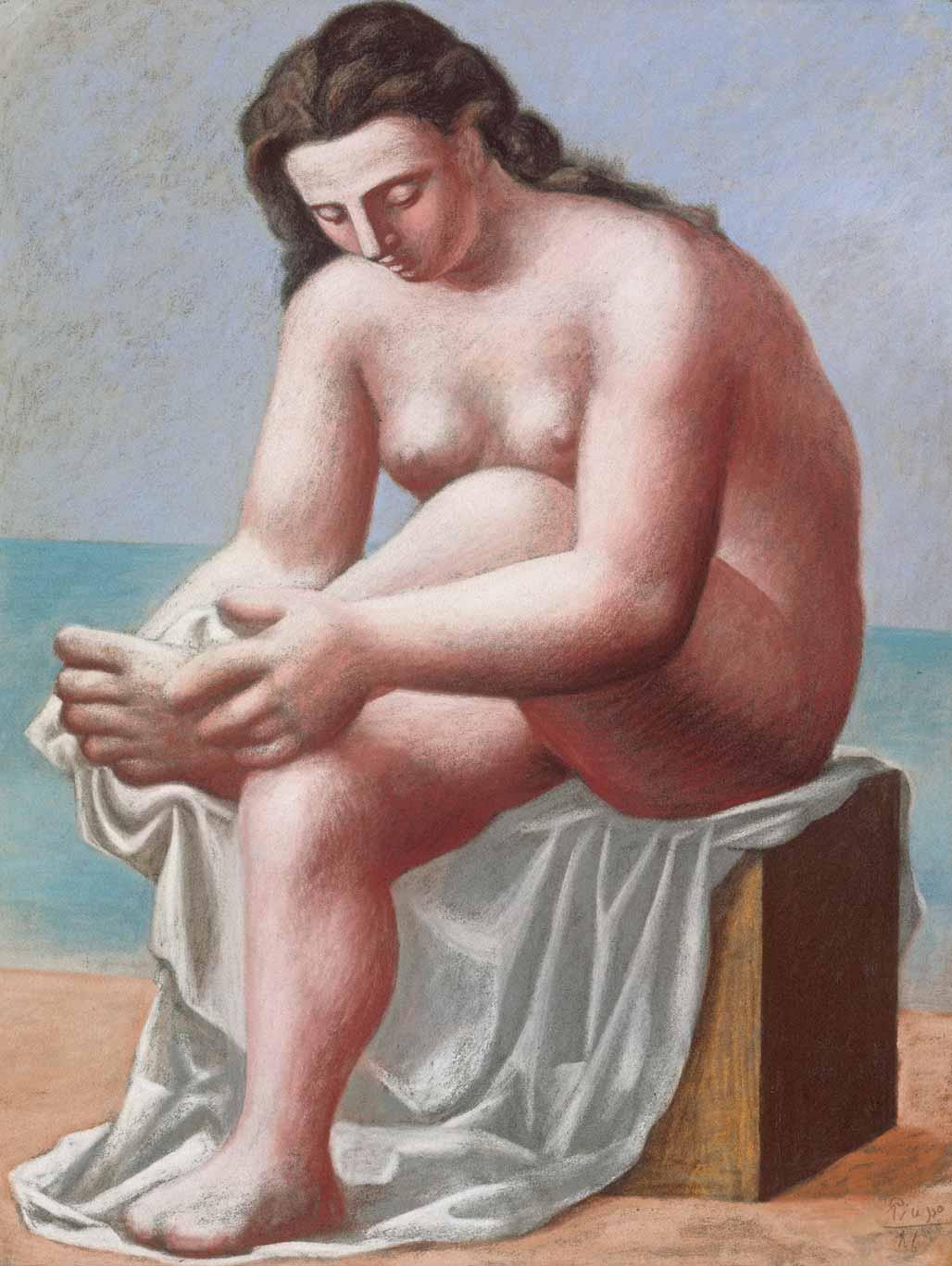

Symbolism presents an interesting case: at first glance, the works of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Gustave Moureau, and Pierre-Amédée Marcel-Béronneau appear to idealize the classical tradition, including works that pay tribute to the heroic male nude.

“I guess you could qualify that as an academic style because it's kind of dark,” Dr. Vivien Greene, senior curator at Guggenheim specializing in 19th- and 20th-century European art, tells Art & Object, referring to the aforementioned heroic nudes. In her 2017 exhibition Mystical Symbolism: The Salon de la Rose+Croix in Paris, 1892–1897, Dr. Greene demonstrated how symbolism was a crucial precursor to modernism. “You know, there's three-dimensionality, but in the subject matter itself, and how we chose to portray or paint it, it's so completely over the top and exaggerated, it's that kind of addressing what's underneath, but that makes it symbolist.”

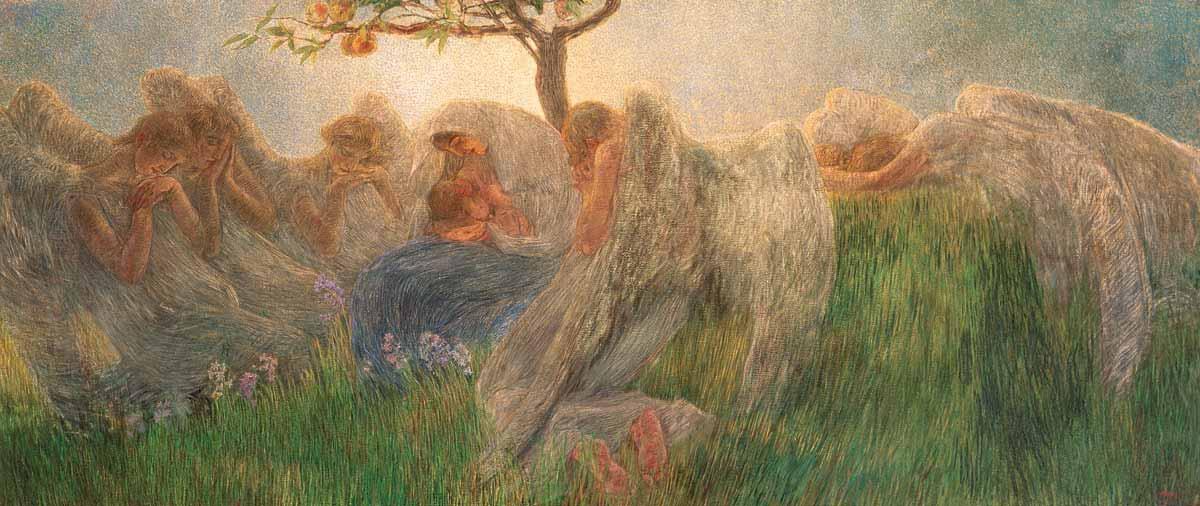

This is true in a country like Italy, too: Dr. Greene pointed out that the way Italy is, by its own nature, an open-air museum of art led it to cling to tradition more than its neighboring countries. Yet, a painter like Gaetano Previati, whose Mother and Child, a symbolist rendition of Mary and the Infant Jesus surrounded by ethereal angels in a grove was deemed unorthodox when first shown in Milan in 1891, yet was accepted in Paris the following year. He was known for a painting technique known as divisionism, the Italian response to French pointillism. “[Divisionism] is more academic in certain ways, but it leads to futurism,” Dr. Greene told Art & Object. “It is modernist while still not fitting that more classical or traditional French definition of modernism.”