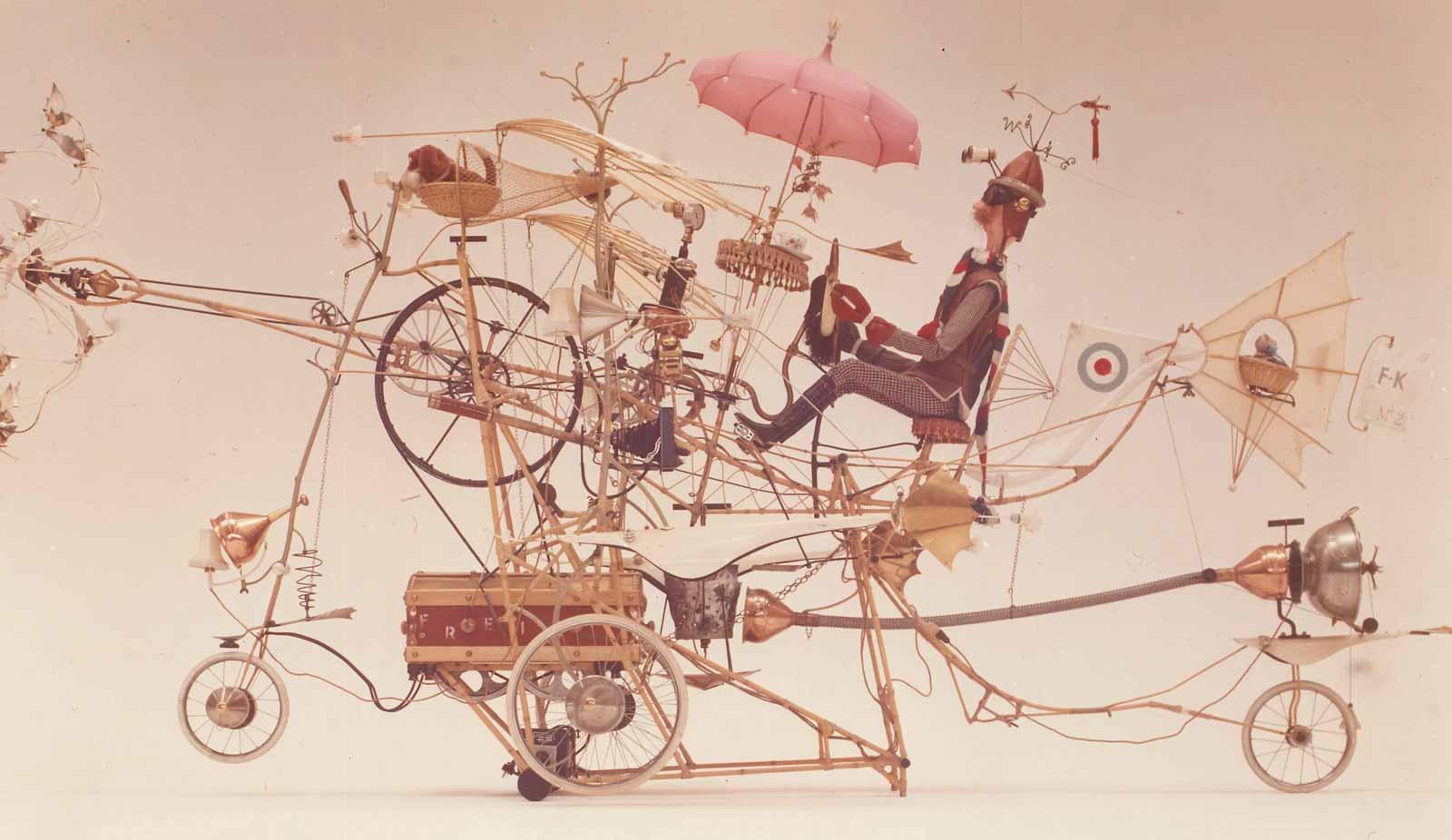

If you’ve ever sat through the 1968 musical film, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, you’ll have come away with two things: an earworm (Chitty Chitty Bang Bang! Chitty Chitty Bang Bang! We love you!), and an appreciation for the protagonist, a quirky but lovable inventor named Caractacus Potts, played by Dick Van Dyke. While Potts’ inventions never quite get off the ground, Rowland Emett, who designed and fabricated the fantastical machines featured in the movie, was a hugely successful artist whose elaborate kinetic sculptures continue to delight viewers of all ages.

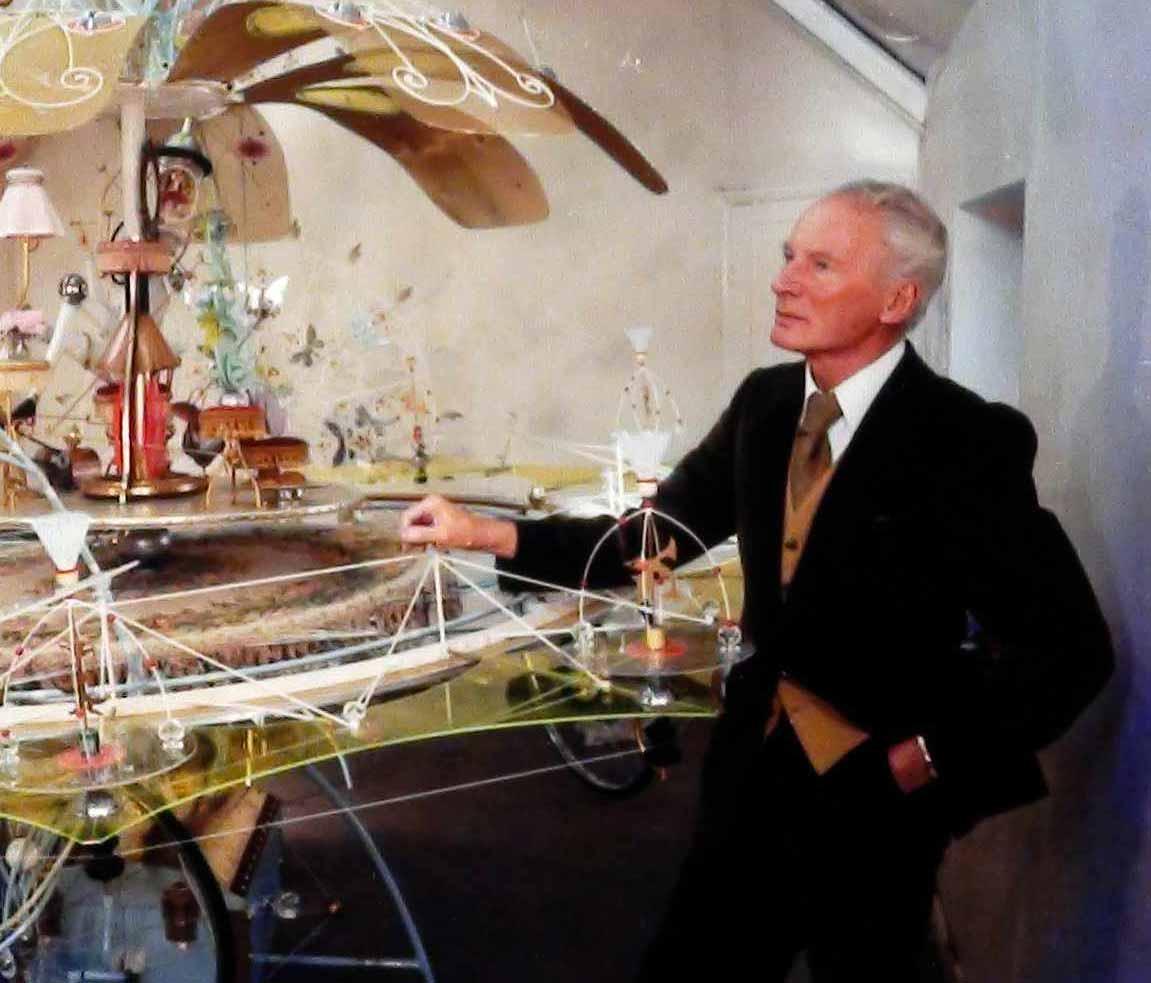

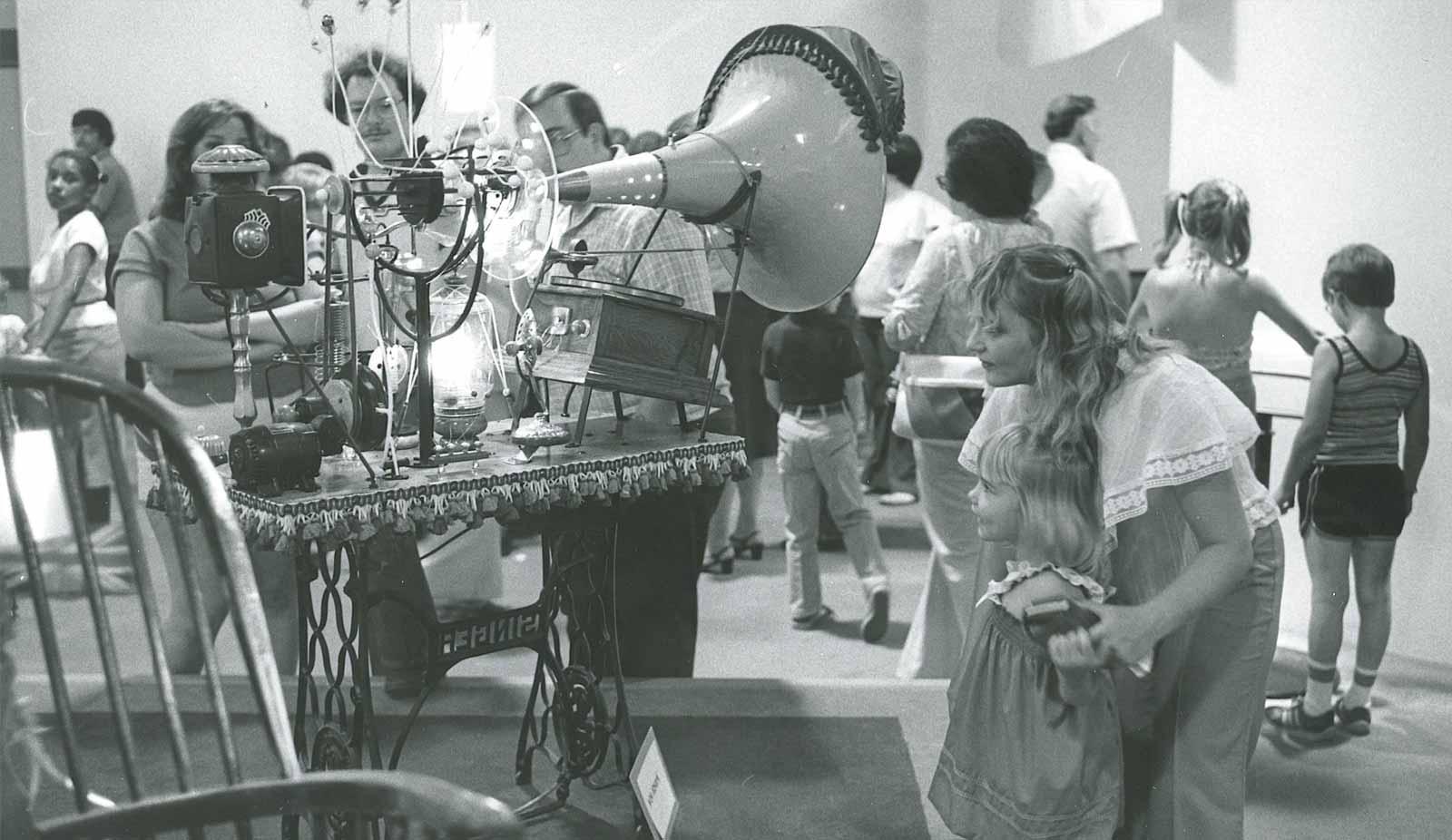

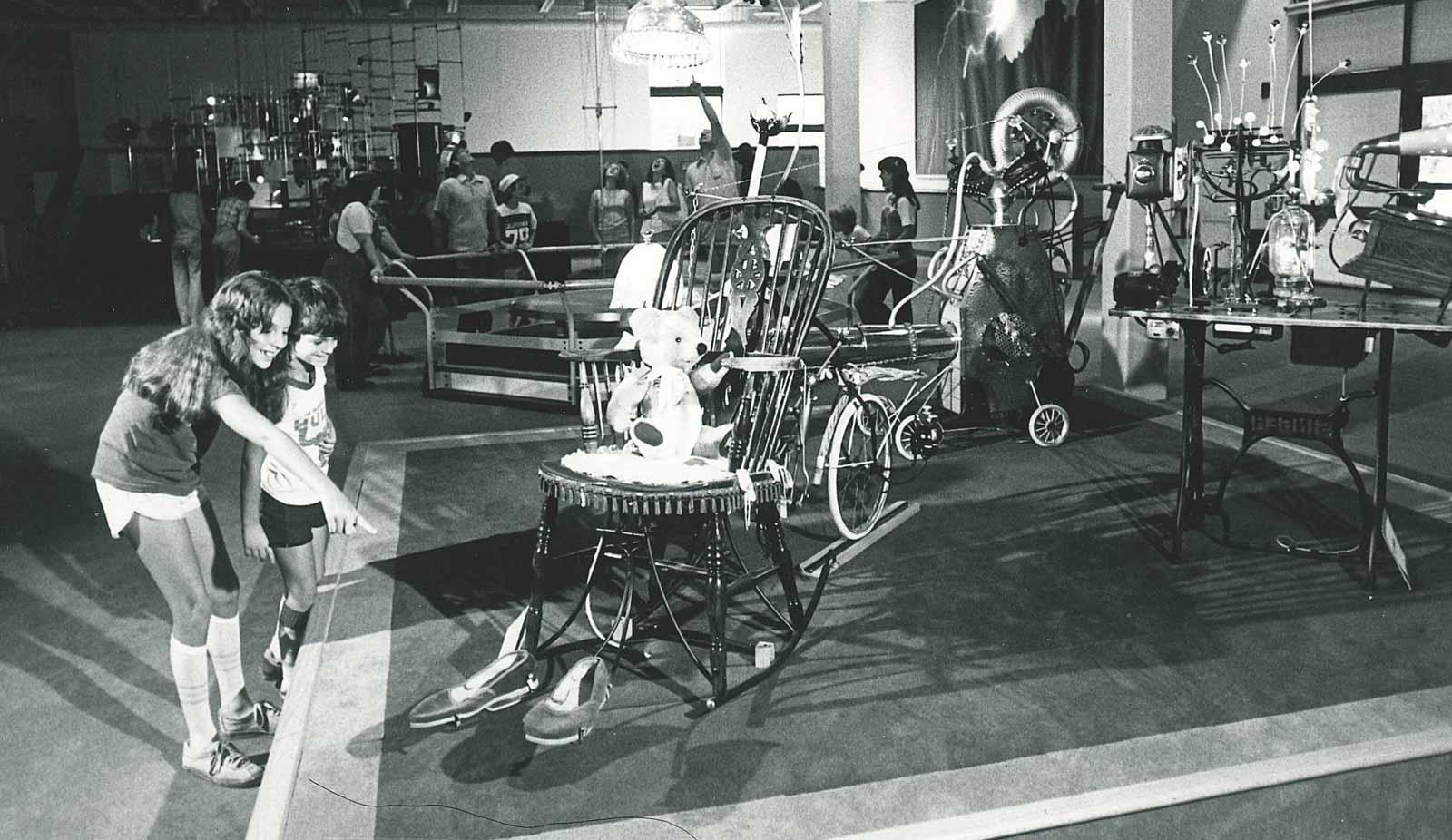

“They’re a wonder to behold,” said Tim Griffiths, founder of the Rowland Emett Society. Griffiths’ experience as a child seeing Emett’s automata on tour in Birmingham, England, sparked a lifelong interest in the artist, which he now channels into collecting, as well as locating Emett’s machines around the world and helping to get them out of storage and on view. In 2014, he organized a major exhibition at the Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery that showcased thirteen machines and over 100 original artworks.

One of the exhibited machines was slated for auction for the first time earlier this month at Bonhams in London. A Quiet Afternoon in the Cloud Cuckoo Valley, made in 1984, was Emett’s largest and last completed kinetic sculpture before his death in 1990—some have called it his masterpiece. As in many of his works, a train dominates the piece, while a closer look at the spinning and bobbing bits of painted metal and wood reveals intricate details like a conductor roasting teacakes, a farmer serenading cows, and a fisherman netting a mermaid. It had been on display at London’s Spitalfields Market and was then put in storage for almost twenty years before nearly being sold for scrap. Once saved, it was fully restored. Just prior to the auction, the owner accepted a six-figure offer from the National Railway Museum in York, England, according to Bonhams. Emett fans are glad to see the “quintessentially English” work of art remain in the country.