The story of the indigenous Yanomami people of the Amazon is fraught with political battles, environmental disasters, and cultural intrigue. For decades anthropologists have argued among themselves for the right to tell the true story of the Yanomami. American anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon (1938-2019) who the New York Times dubbed “ the most controversial anthropologist in the United States” characterized the image of the Yanomami as The Fierce People, the title of his widely referenced book published in 1968. Chagnon, along with his colleague, ethnographic filmmaker Timothy Asch (1932-1994), were pioneers in visual anthropology. They made a series of over twenty films depicting everyday life while living with the Yanomami in the 1960s and 1970s.

Who Speaks for the Yanomami? The ongoing Yanomami Struggle told through art

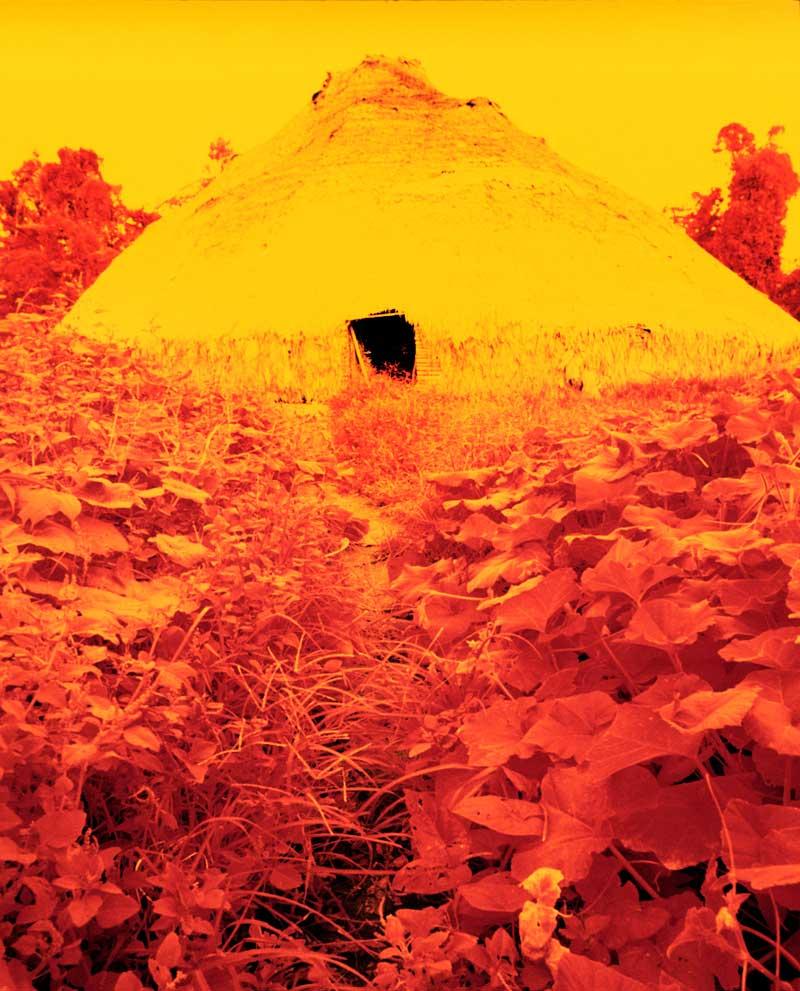

Collective house near the Catholic mission on the Catrimani River, Roraima state

The Yanomami Struggle, a comprehensive exhibition presented at The Shed in New York City is dedicated to the collaboration and friendship between artist and activist Claudia Andujar and the indigenous Yanomami people of the Amazon.

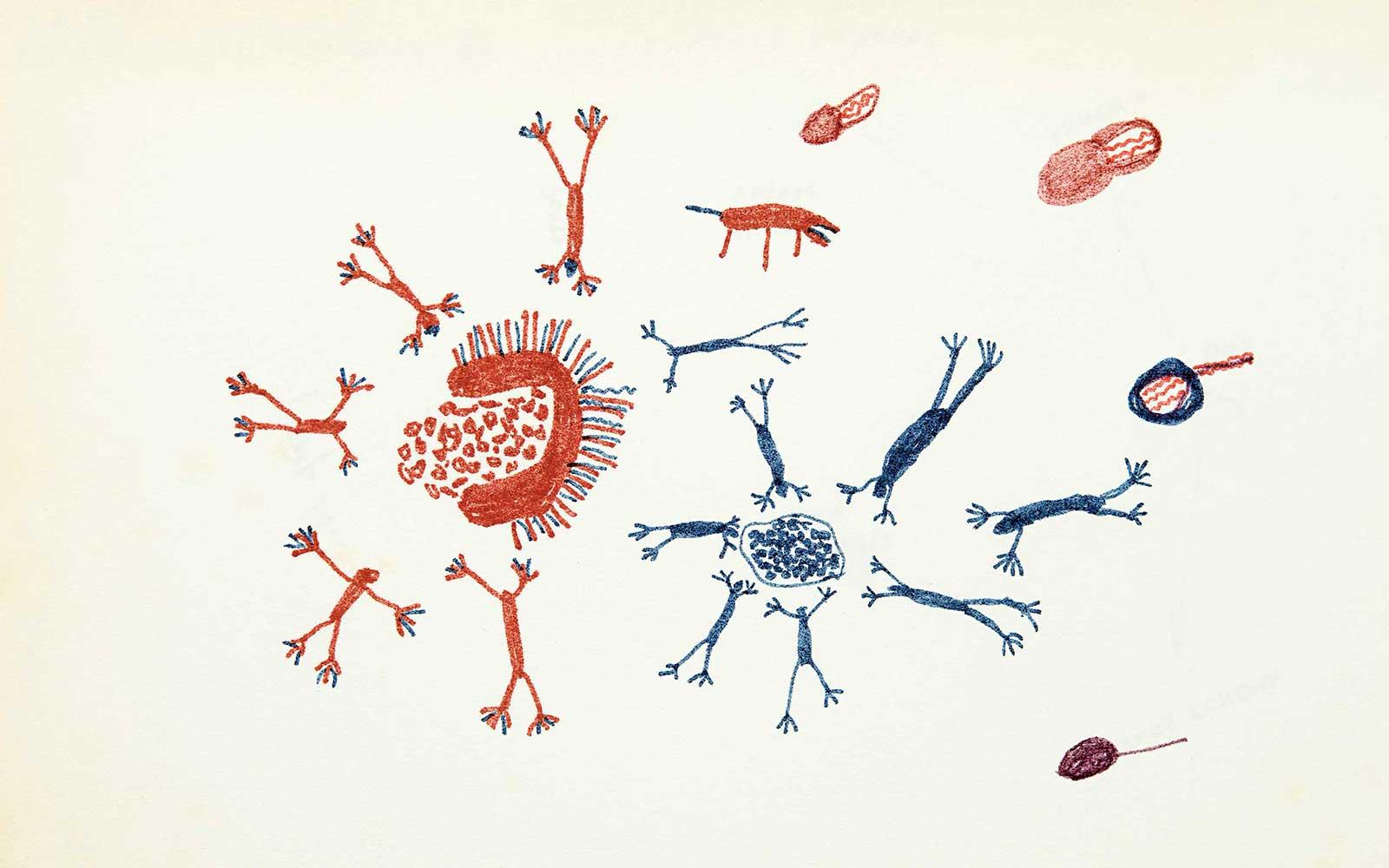

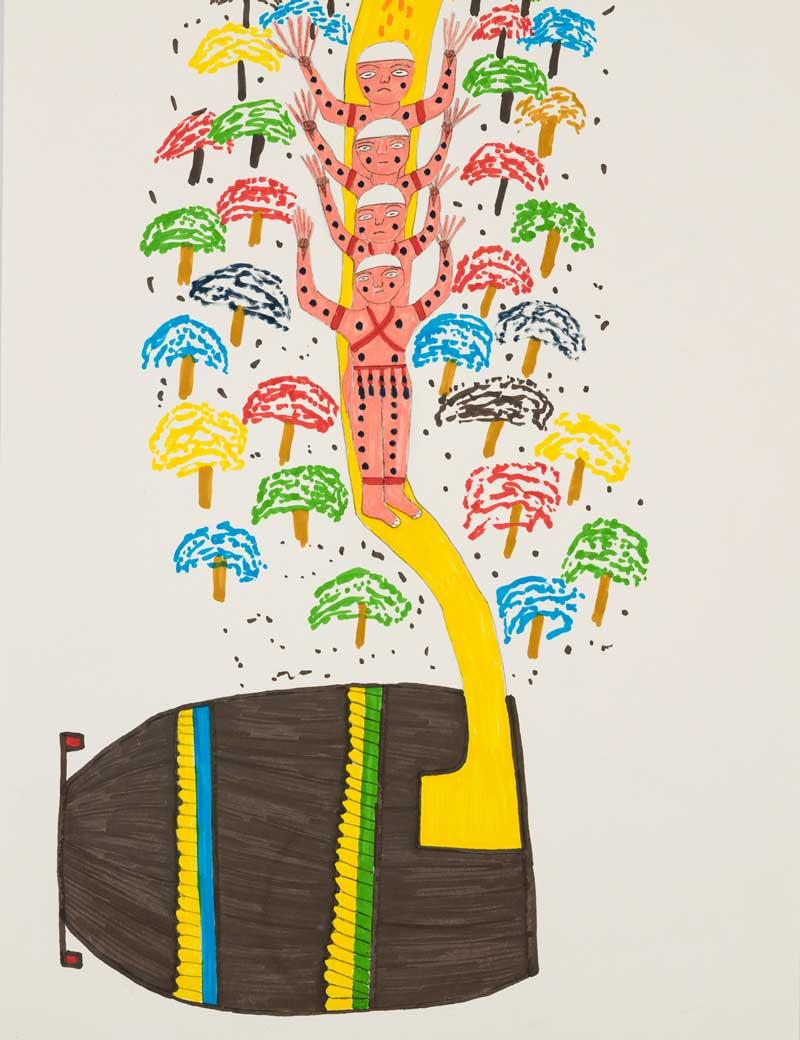

Such are the paths of the xapiri when they descend into the house of the shamans

The show featured 200 photographs by Claudia Andujar alongside more than 80 drawings and paintings by Yanomami artists.

Collective house surrounded by sweet- potato leaves, Catrimani region

The Ax Fight, a structurally experimental film shot spontaneously upon their arrival in a village deep in the Amazon in 1971 analyzes a violent altercation in that Yanomami village. The film has been a key component in college anthropology courses since its release. Asch was instrumental in the founding of the University of Southern California Center for Visual Anthropology. Ultimately, Asch disputed Chagnon’s characterization of the Yanomami and he went on to edit several short films representing a less aggressive presentation of village life.

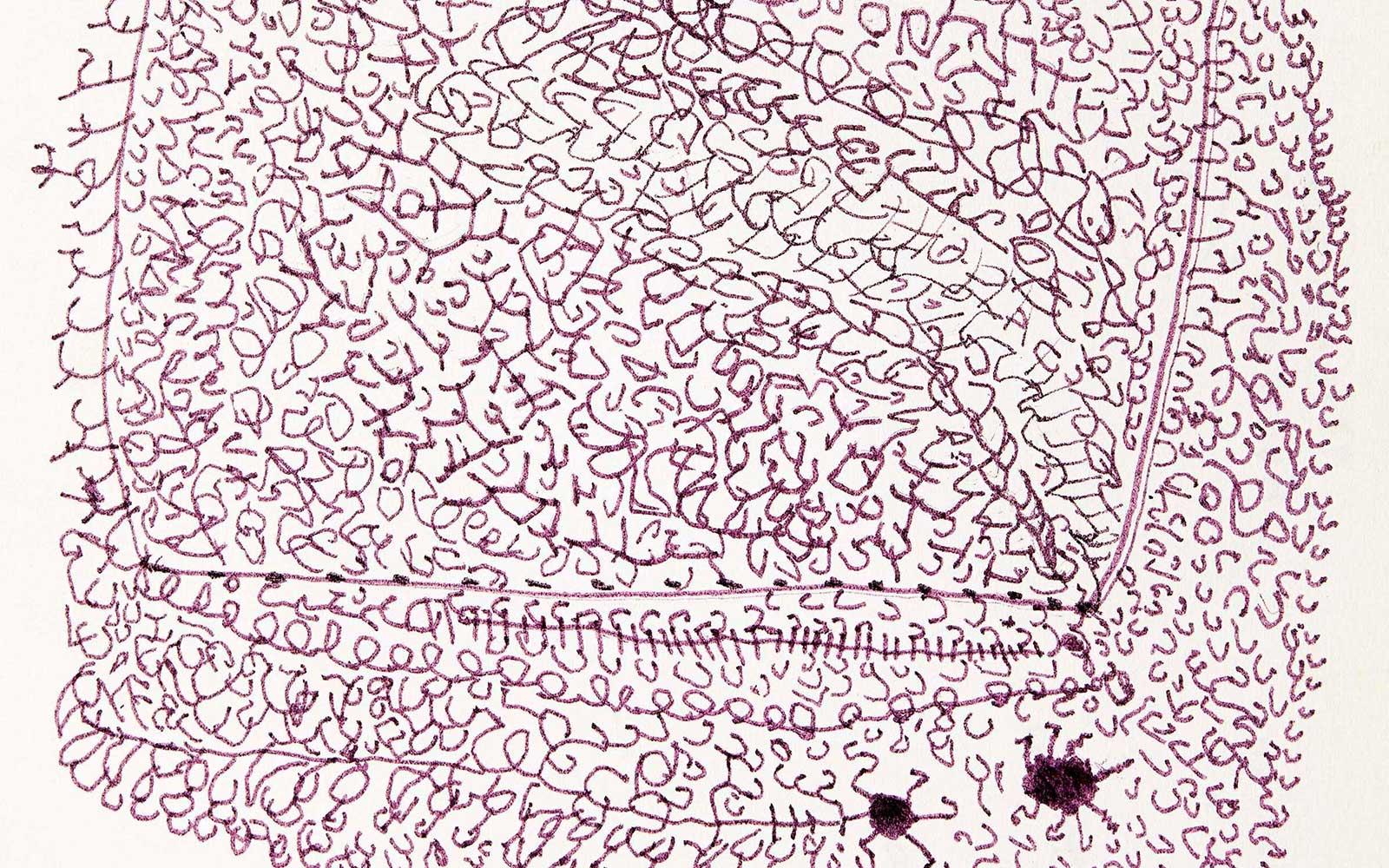

This spring, The Yanomami Struggle, a comprehensive exhibition presented at The Shed in New York City was dedicated to the collaboration and friendship between artist and activist Claudia Andujar and the Yanomami people. It was the result of an international effort and collaboration with the Instituto Moreira Salles, São Paulo, Brazil (IMS), and was made possible by the Fondation Cartier and The Shed in partnership with the Brazilian NGOs Hutukara Associação Yanomami and Instituto Socioambiental. The show featured 200 photographs by Andujar alongside more than 80 drawings and paintings by Yanomami artists André Taniki, Ehuana Yaira, Joseca Mokahesi, Orlando Nakɨ uxima, Poraco Hɨko, Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe, and Vital Warasi. While much of the work could be characterized under the umbrella of Naïve Art, these artists are not bound by pervasive “primitive” stereotypes. They use a wide range of media and have embraced technology as evidenced in new video works by contemporary Yanomami filmmakers Aida Harika, Edmar Tokorino, Morzaniel Ɨramari, and Roseane Yariana. Shown together in New York for the first time, Adujar’s photos in dialogue with contemporary Yanomami artwork open a new chapter in this ongoing saga about indigenous identity and whose voices will be heard in defining that identity.

Born in Switzerland in 1931, Andujar immigrated to New York in 1946 after escaping persecution by the Nazis. Her father, of Hungarian and Jewish descent, died in the Dachau concentration camp. Andujar’s family history informed her search for meaning and led her to a career in photojournalism. In 1956, she moved to Brazil to join her mother. In the 1970s, the Brazilian government was under a military dictatorship and was responsible for opening the Amazon to mining, ranching, and logging, building roads, and bringing death, disease, and destruction to Yanomami territory. As a photojournalist, Andujar was drawn to cover this story and in 1974 she decided to spend an entire year living with the Yanomami, a year not taking photographs, but getting to know the people. The experience fostered lifelong friendships and resulted in a body of intimate, and often breathtaking images that transcend the boundaries of time and place expanding into realms beyond the physical. “She uses multiple exposures, or shakes the camera with the aperture open to create blurs of light, like drawings in the sky or on the ceilings of malocas,” said Thyago Nogueira, the head of contemporary photography at the Moreira Salles Institute and a curator of The Yanomami Struggle. “There are a series of artifices that she builds to create this translation of worlds, to help us see what they see.” The saturated color, the phantasmagoric magenta, and red/orange of earth on fire, mirror the intensity of the artist's experience.

Adujar’s work was supported by Guggenheim Fellowships in 1971 and 1977. Her work was such a powerful tool, that the military government of Brazil expelled her. Despite her precarious situation she has continued to document the Yanomami in the ensuing years. In Yanomami: The House, The Forest, The Invisible a book published in 1998, Adujar states, “My relationship with the Yanomami, the guiding force of both my career as a photographer and my life, is essentially one of fondness. This sentiment, over time, has led me to divide my time as a photographer with activities in defense of that people’s rights to territory and survival. A demanding task and one that requires great perseverance.”

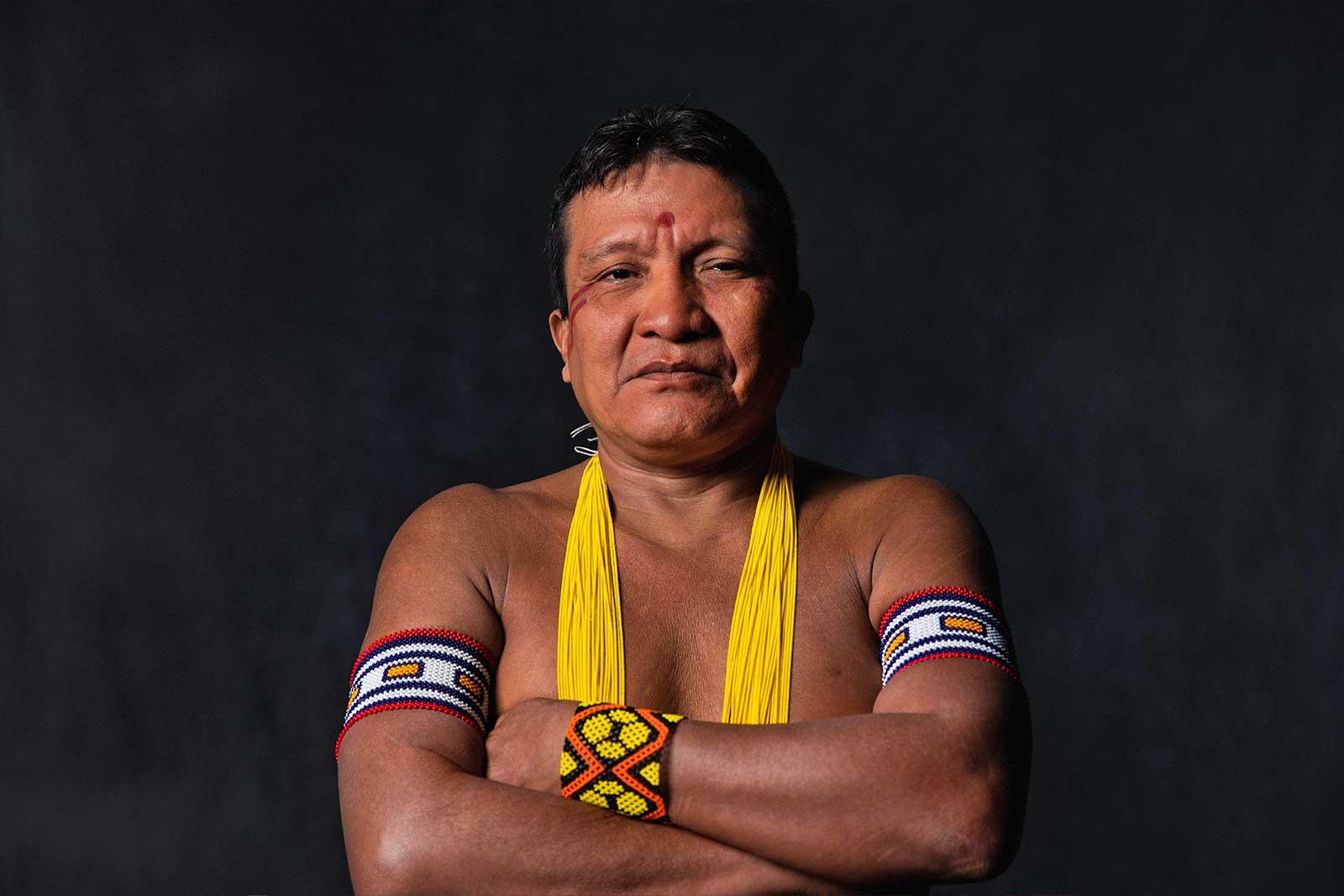

Joining Adujar in this fight to control their territory and their basic human rights is shaman and Yanomami leader Davi Kopenawa (b. ca. 1956, Mõra mahi araopë community, Marakana region). He serves as a guide to assist in the interpretation of the vision of Yanomami life as presented through these artists' works. His drawings and quotes from his book The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman (co-authored with anthropologist Bruce Albert, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013) are included throughout this exhibition.

Under the leadership of Brazil from 2019-2022 the right-wing government of Jair Bolsonaro declared open season on what is left of the Amazonian environment. Under newly elected President Luis Inácio Lula da Silva, things appear to be changing, for the better. In one of his first acts as president, Lula issued rulings that revoked or altered Bolsonaro’s anti-Indigenous and anti- environmental decrees. While exhibitions like The Yanomami Struggle can raise awareness and stimulate dialogue, the challenges facing indigenous people are synonymous with the threats to the environment and by inference the threats to the future of the entire human race. At the age of 92, Claudia Andujar has no illusions about the impact of her work. “I think my photos helped back then,” Andujar said, “but they didn’t resolve anything. We still need to fight.” The next generation of Yanomami artists and activists appear ready to face the challenge.

![Andujar-slides01.jpg Hii Hi frare frare [Tree with yellow trunk]](https://cdn.artandobject.com/sites/default/files/styles/media_crop/public/andujar-slides01.jpg?itok=2aM4zCmA)