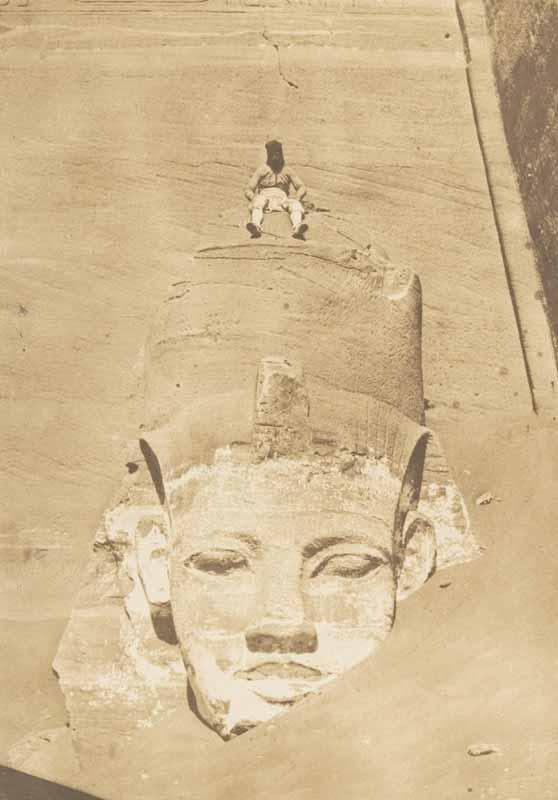

Lugging all the equipment necessary for an eighteen-month photographic voyage, and processing negatives in transit—often in the middle of the desert or an otherwise deserted landscape—was hard. “While traveling he would sensitize and expose the negatives, develop and fix them,” McCauley explains of Du Camp’s technical process.

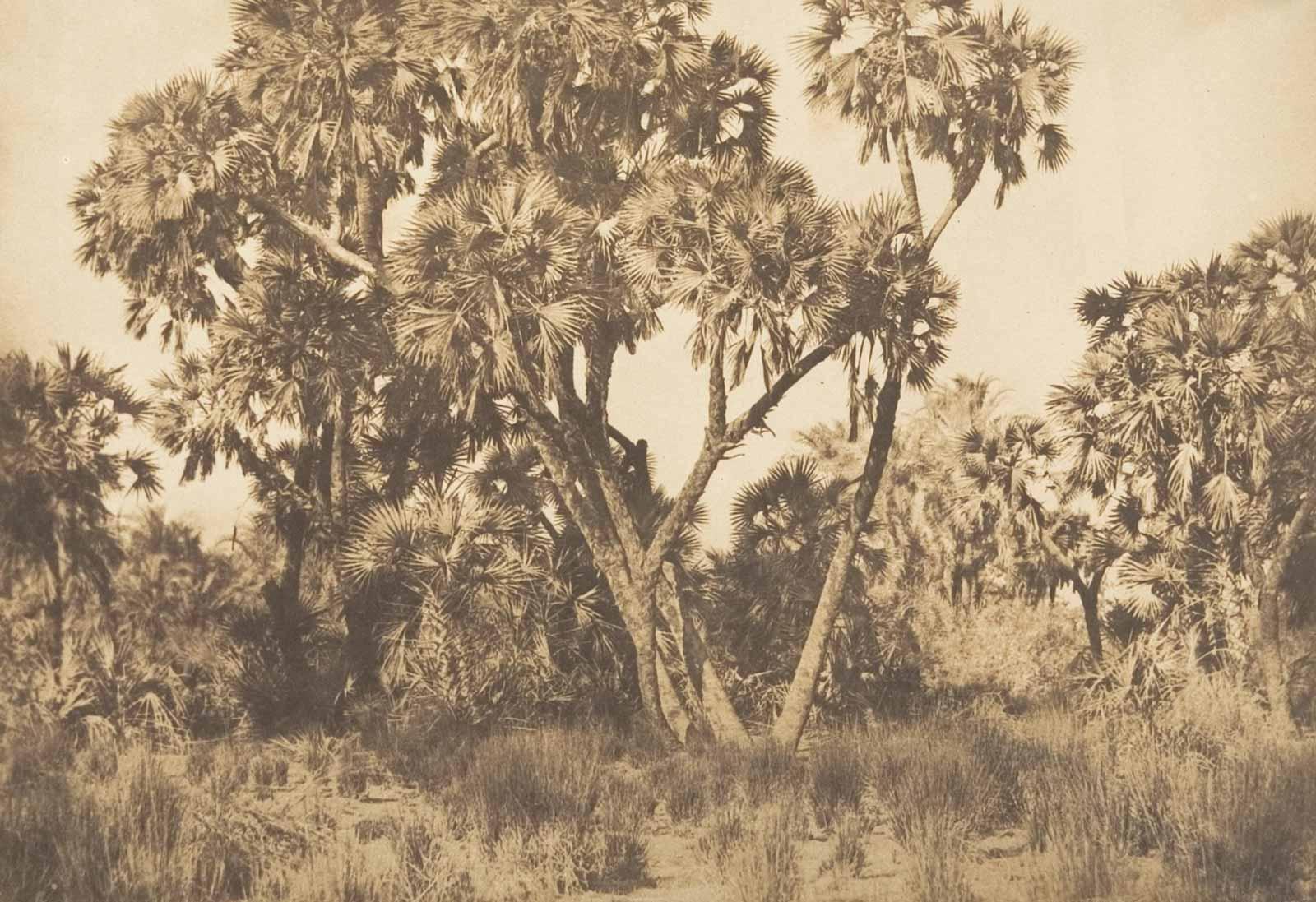

“He had many servants to carry all his paper, camera, chemicals, tents (he would need some sort of dark room either in a wagon or a tent in order to do the chemistry), as well as presumably water,” adds McCauley. “Water was a huge issue in photographing in the desert—you needed distilled and pure water, plus the temperature (heat) was an issue for photographers. All expeditionary photography demanded a team of local guides, porters, camels and horses.”

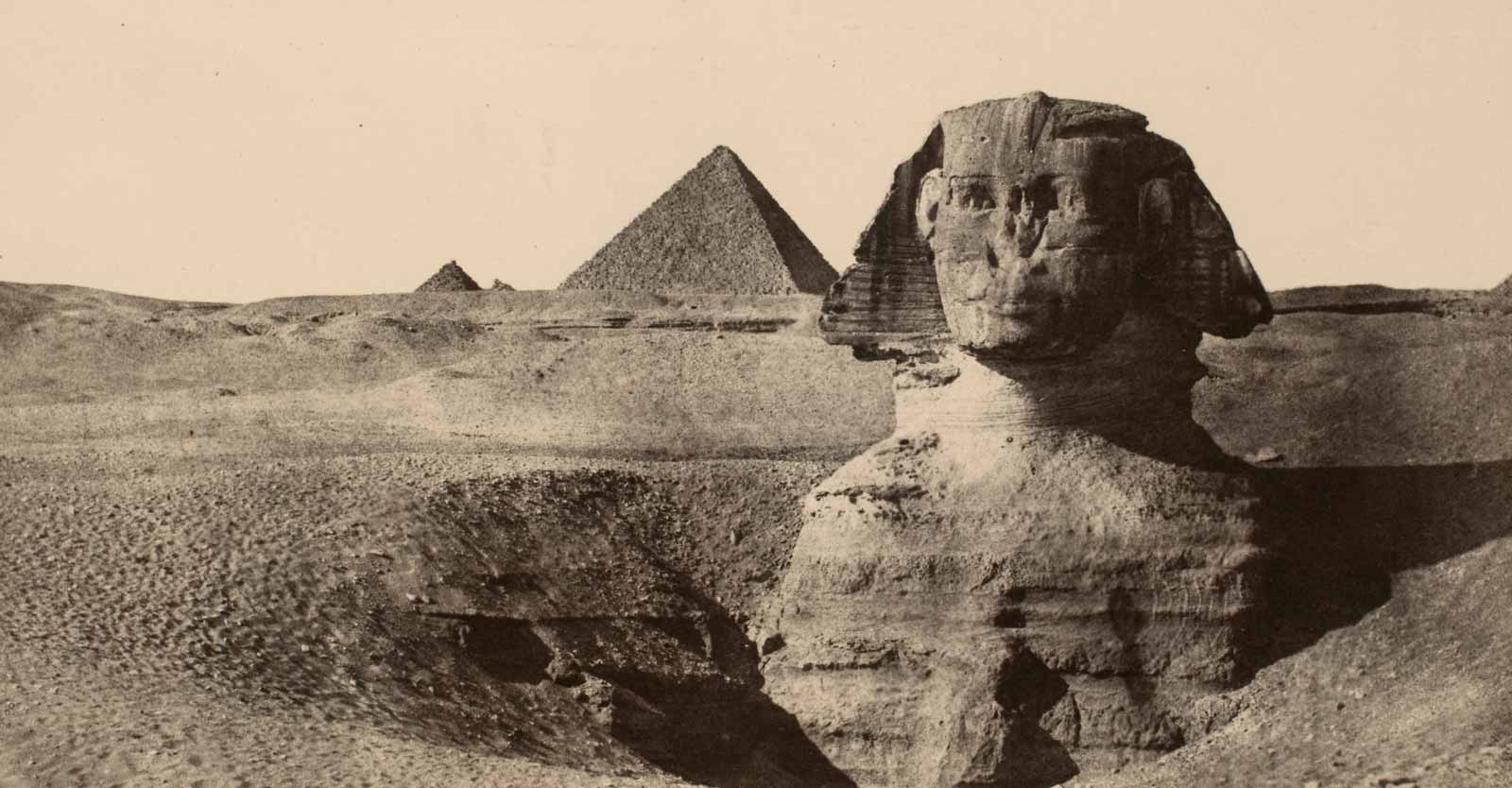

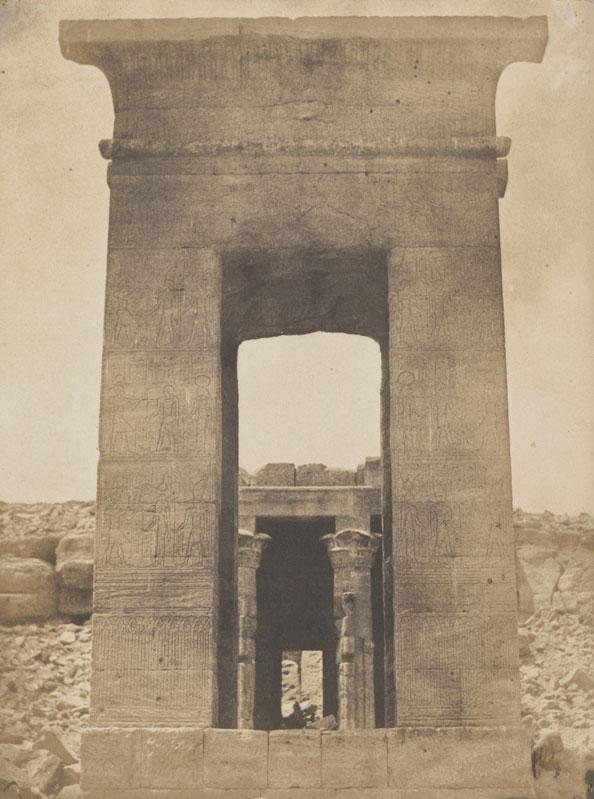

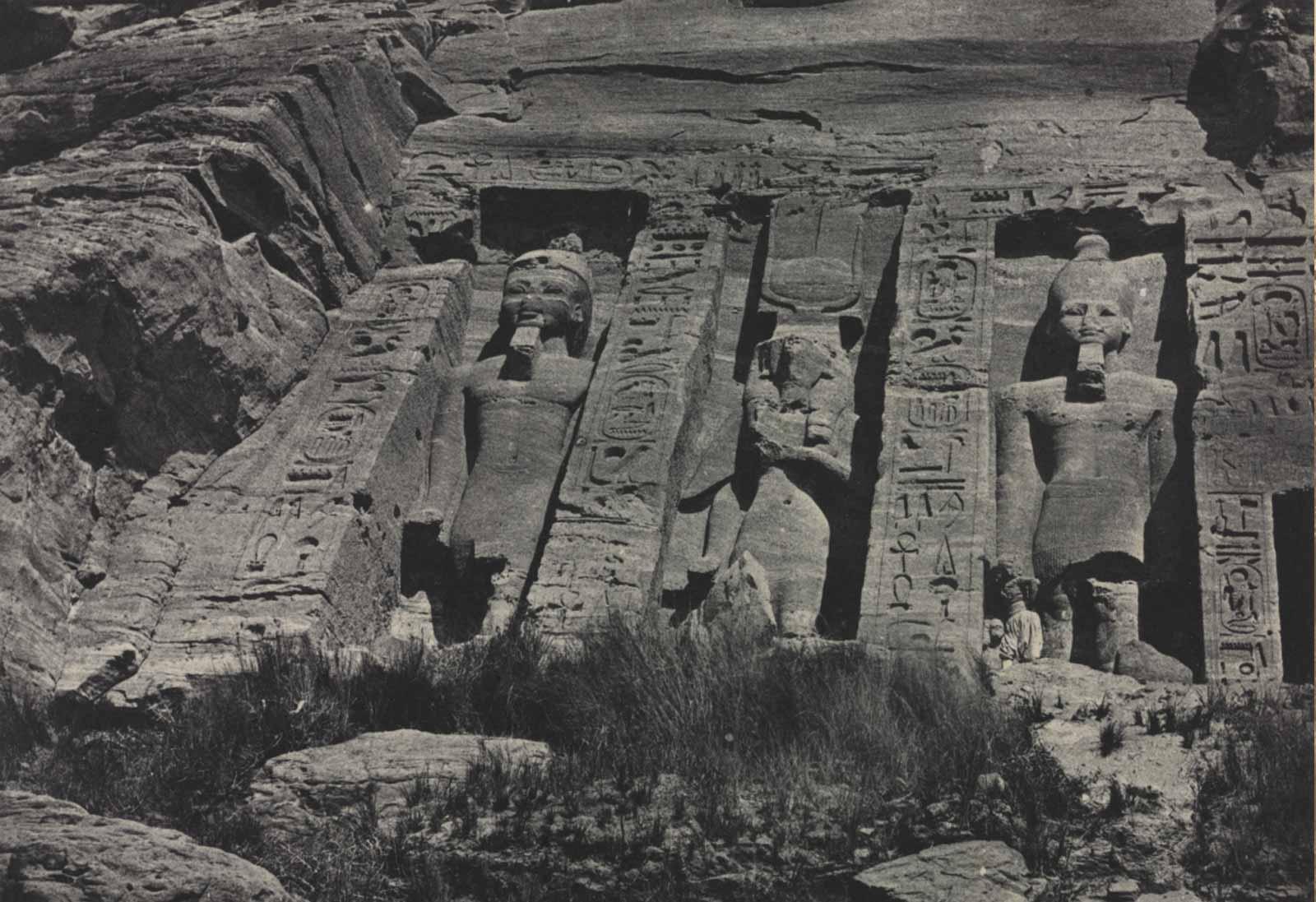

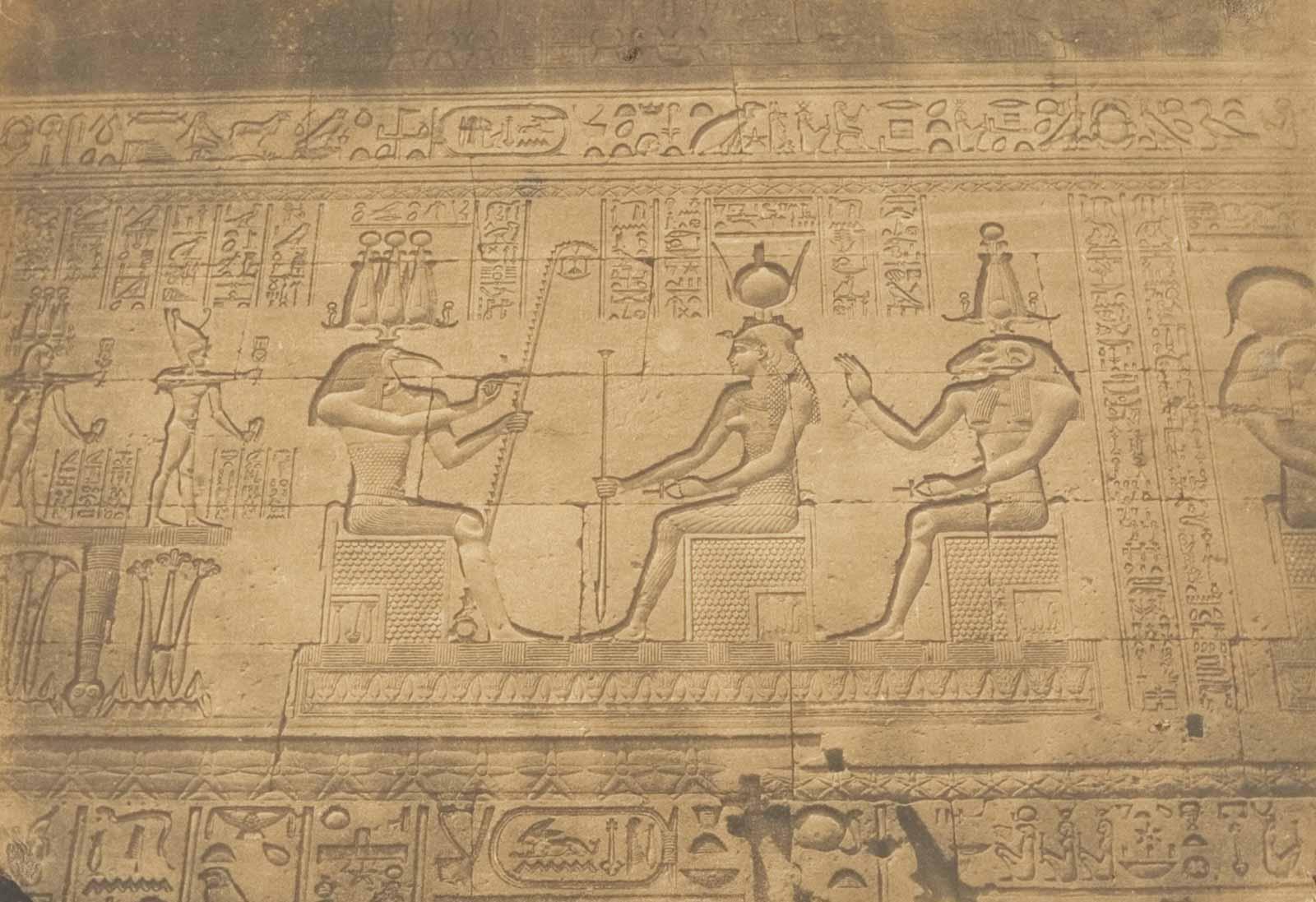

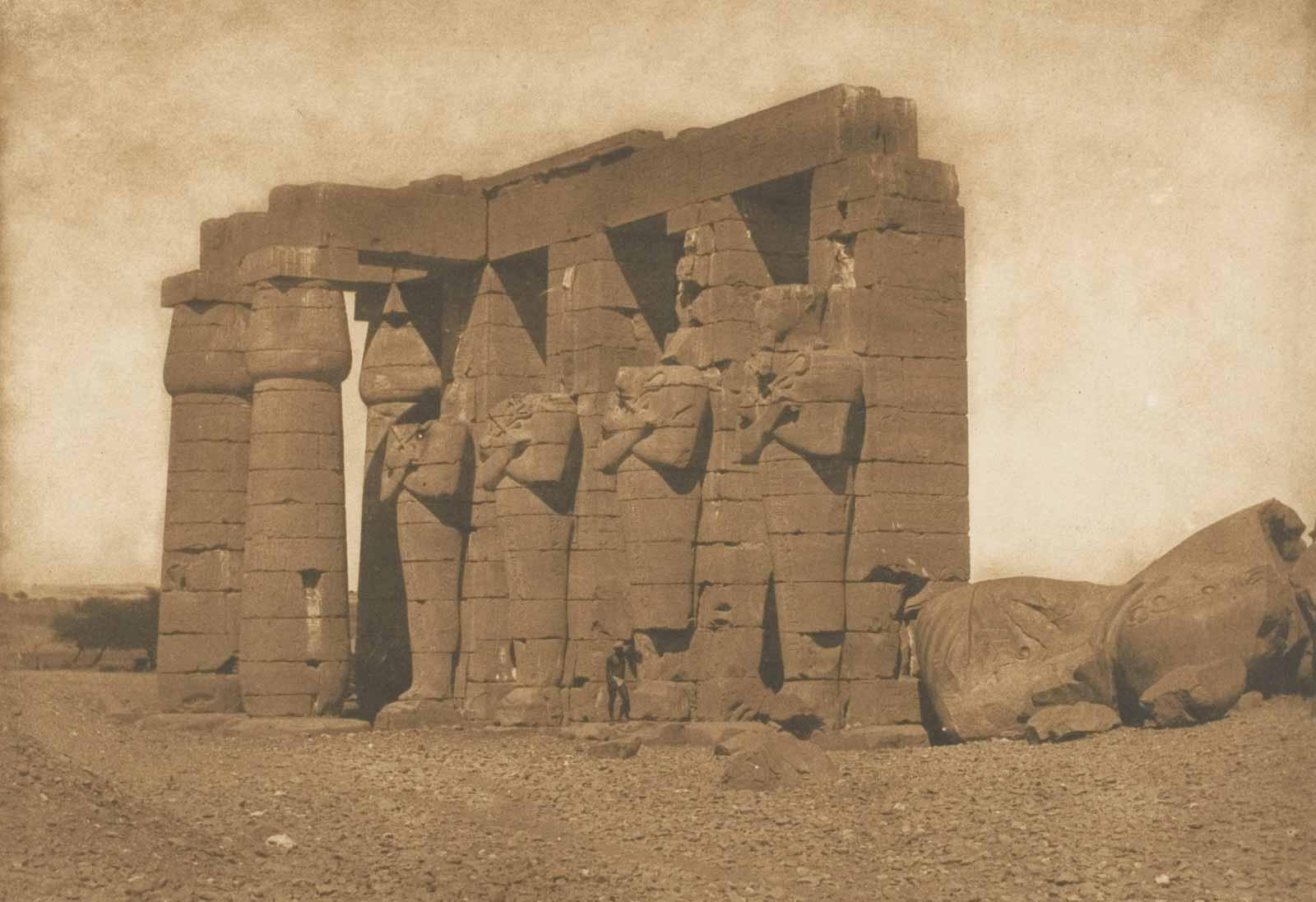

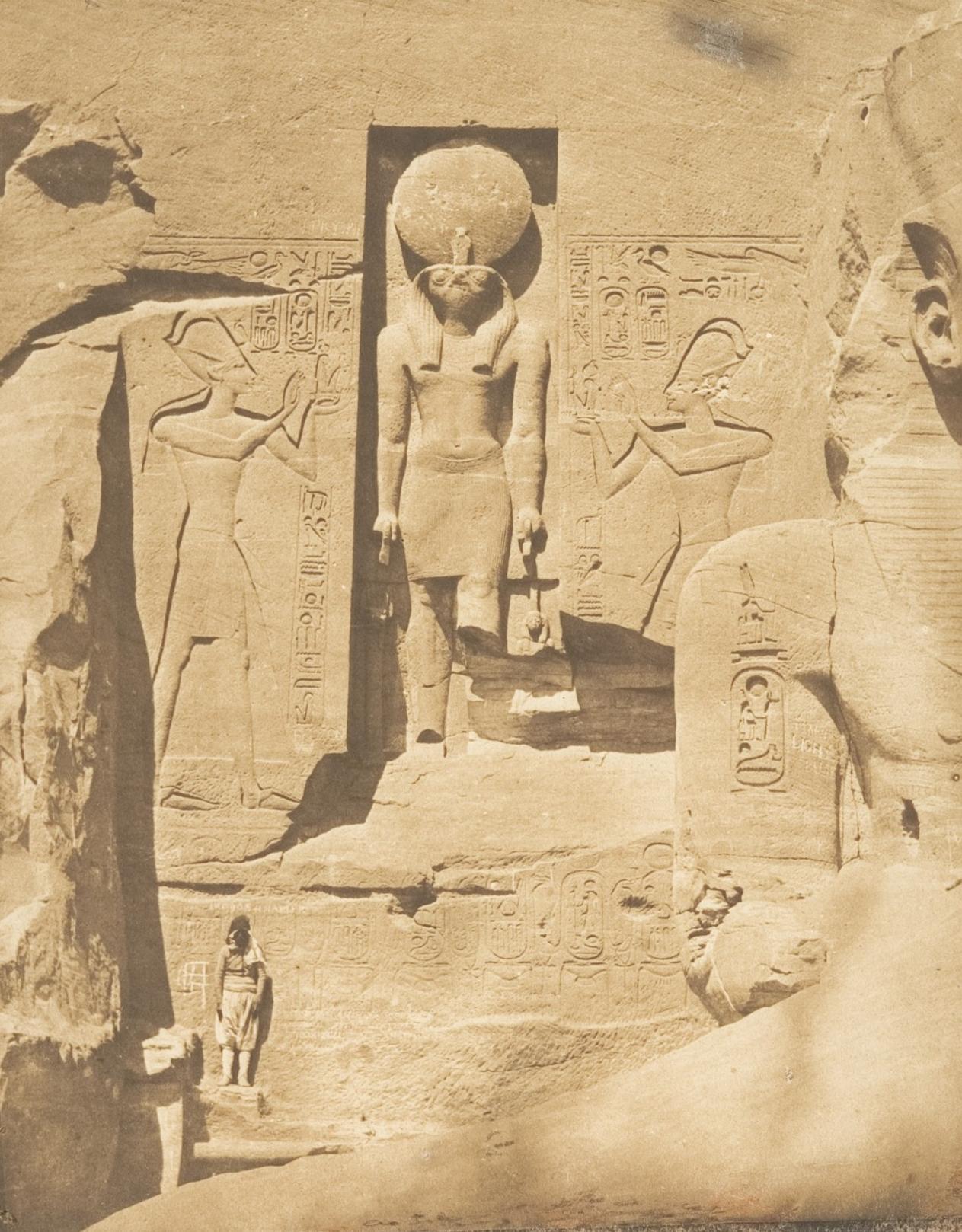

When Du Camp and Flaubert stayed at the Maison de France in Thebes, for example, they rented an entire room just to store photographic equipment. The arrangement was cumbersome, but seemed to be working: Du Camp produced 189 sharp images of ancient Egyptian relics.

But by the time he reached Beirut (his destination immediately after Egypt), Du Camp started having more and more trouble with his chemical baths and exposures. As a result, he only made twenty-seven negatives after leaving Egypt.

And by September 1850, less than a year after embarking on his adventure, Du Camp was ready to call it quits on his photographic career. He traded his camera with a zealous amateur in Beirut, in exchange for ten feet of gold-embroidered damask fabric that he’d use to decorate his Parisian home. (Flaubert said that Du Camp planned to use the textile to make a “sofa fit for kings.”)

Du Camp returned to France with noticeably lighter luggage, but also an impressive 214 negatives. The Blanquart-Evrard firm printed a selection of 125 negatives for Du Camp’s book, which was released for public sale in April 1852. The book was a success, bought mainly by archaeologists interested in seeing the Egyptian monuments in high definition without experiencing any of the discomforts Du Camp faced.

And just like that, almost by accident, amateur shutterbug Du Camp made photographic history. He never shot a photograph ever again.