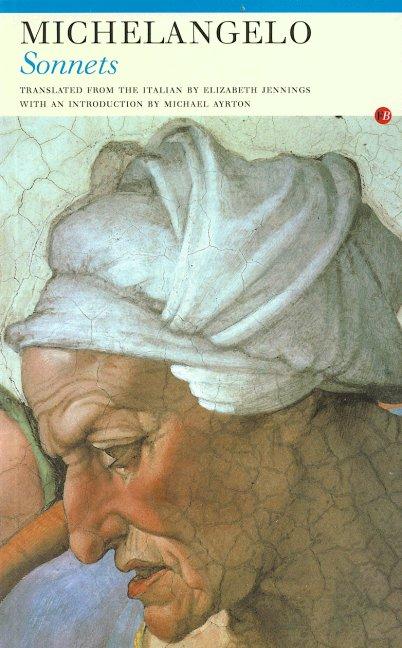

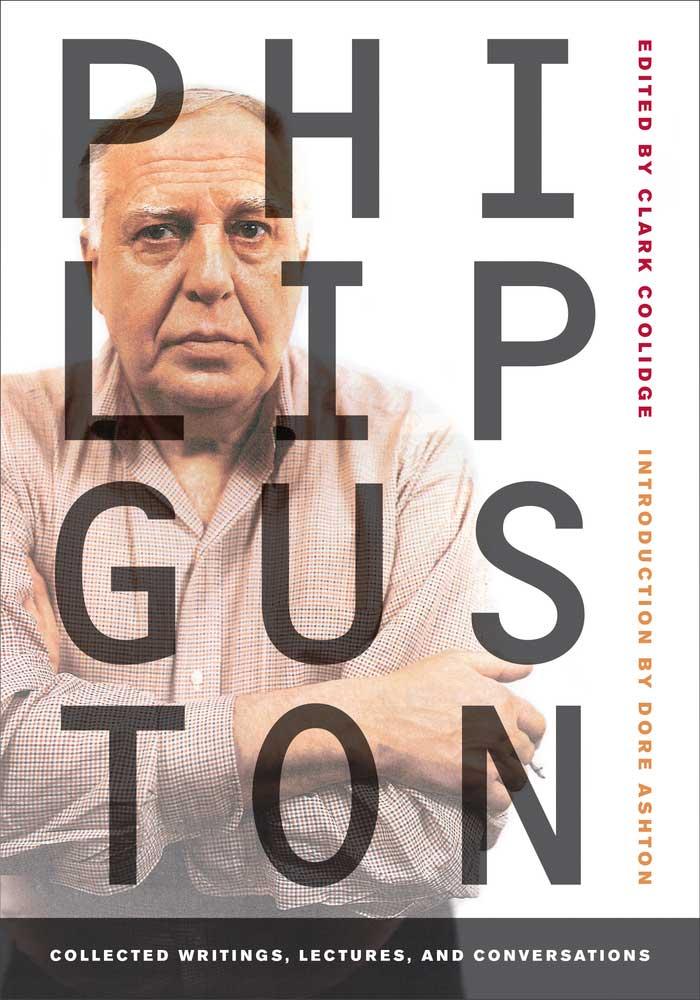

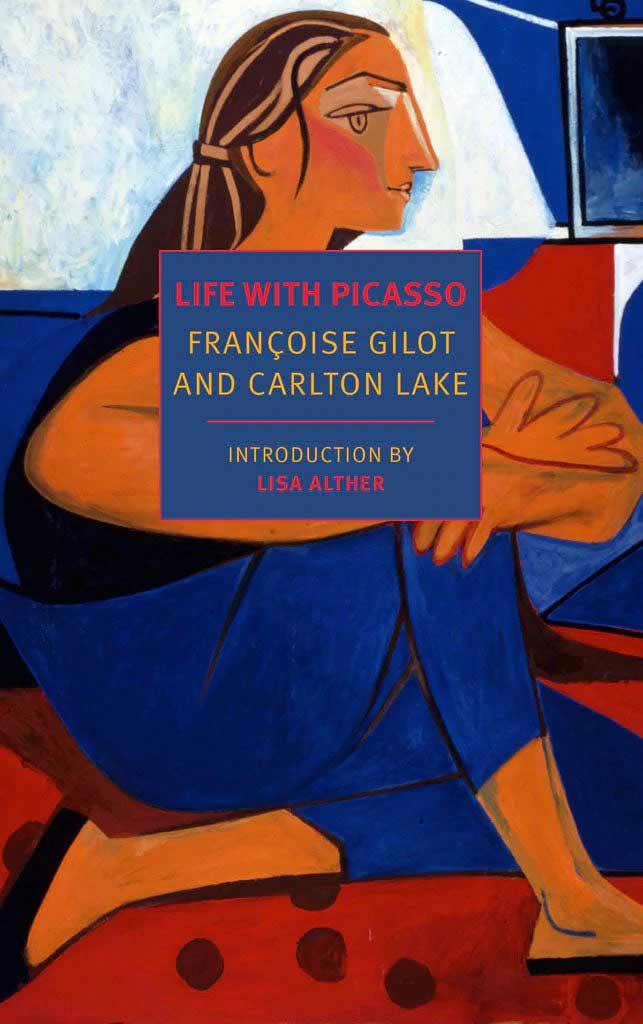

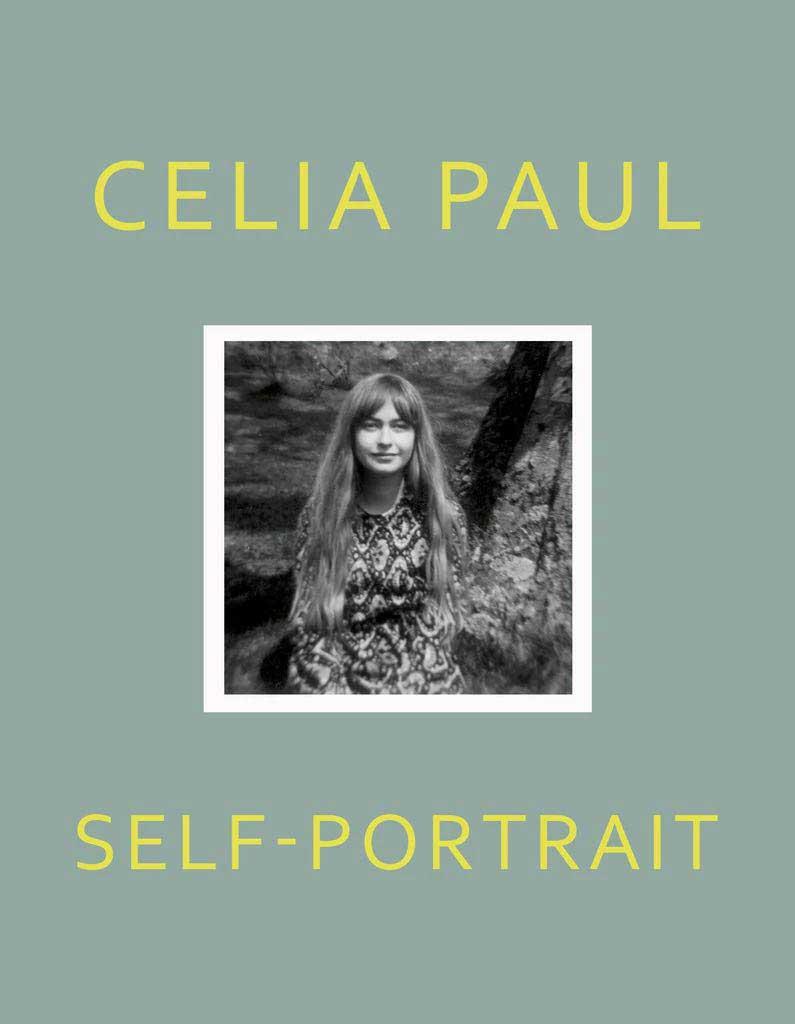

Throughout human history, there are examples of artists who have also written about art.

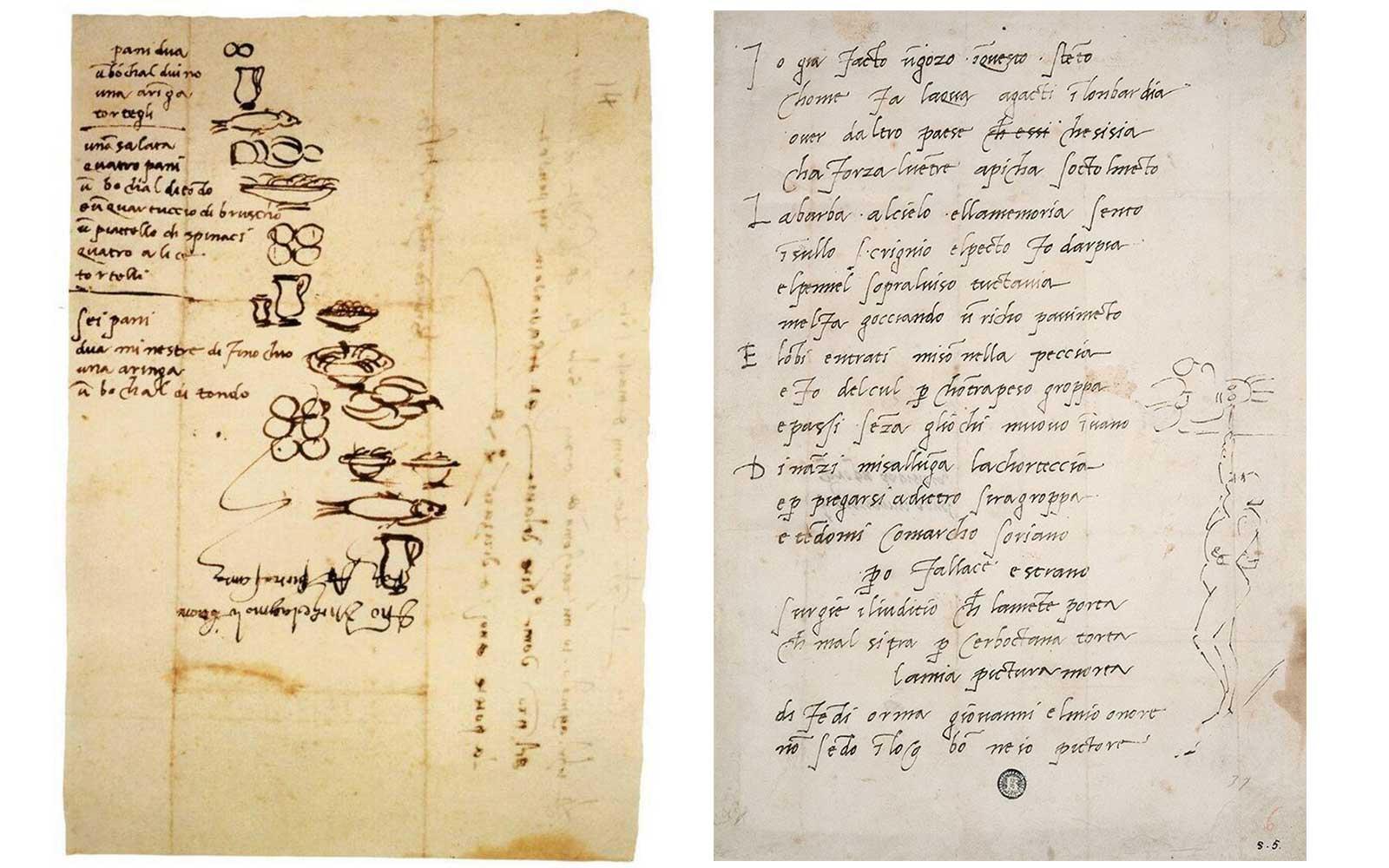

Xenokrates of Sicyon, a Greek sculptor born around 280 BC, is considered one of the world’s first art historians. The painter Apelles wrote about technique in 332 BC. In sixth-century China, Xie He wrote Six Principles of Painting, in which the painter emphasized that ‘spirit’ or energy is of primary importance in painting. Tuscan painter and sculptor Giorgio Vasari published two editions of Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects in 1550 and 1558. Though better known as a writer and historian today, Vasari’s artist

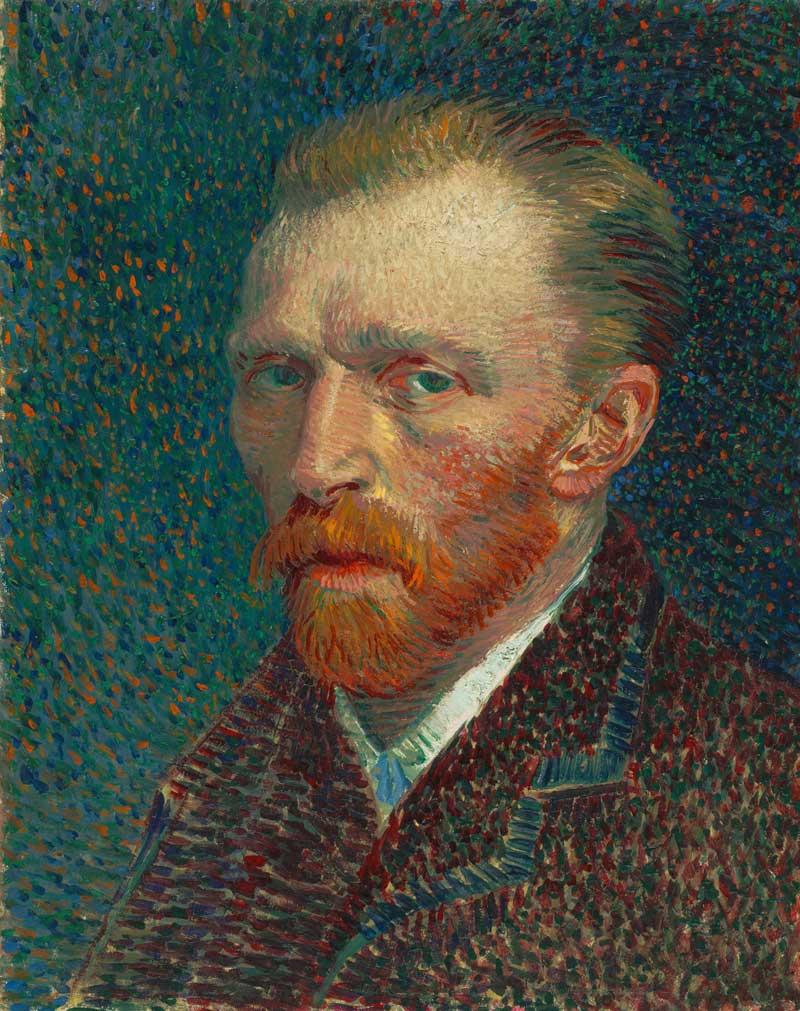

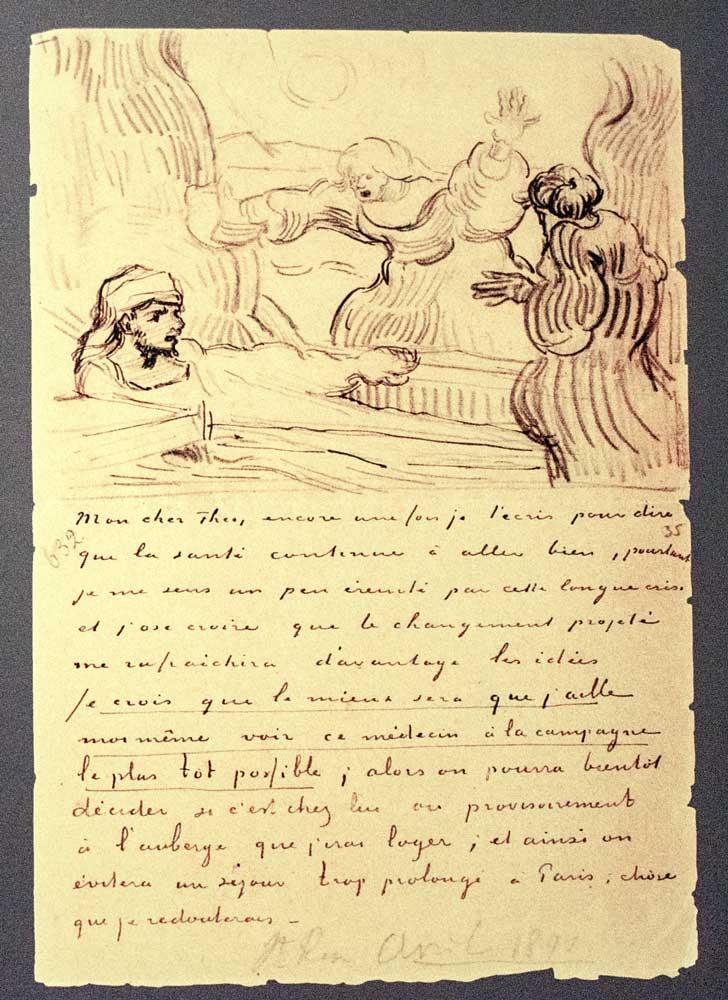

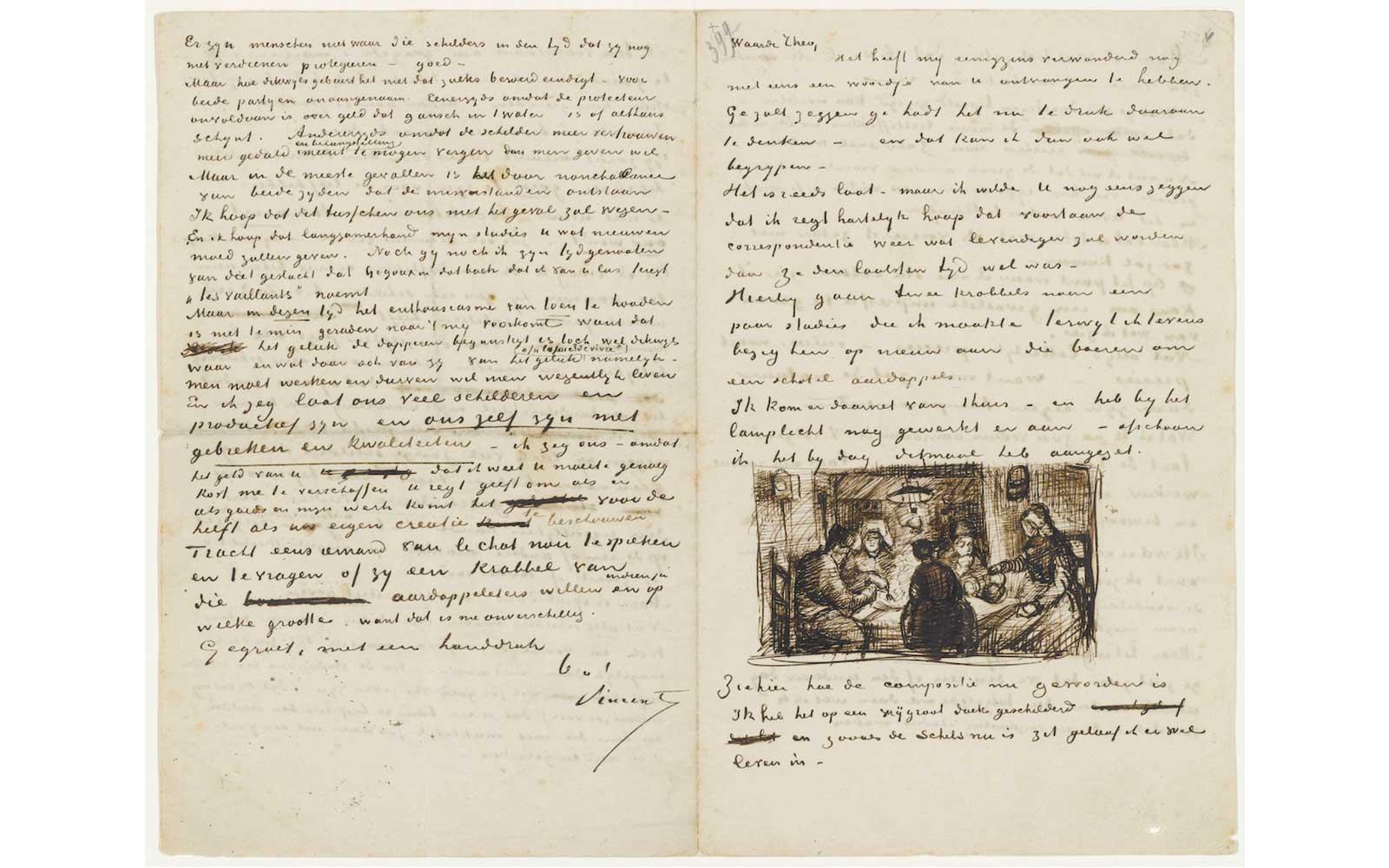

To read the writing of artists is to gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of their work. It allows us to see their work on different levels, which can enrich and embolden one’s relationship with art. Perhaps the most famous artist who wrote prolifically was Vincent van Gogh. He wrote more letters than he produced paintings: approximately 2,000 letters and only 900 paintings. Today, his letters are read by many artists as an astute education to apply to their own work. Van Gogh wrote about color, composition, light and shadow, mediums, and the way he saw people and landscapes. These insights offer, for any reader, a primer on how to see more deeply and an understanding of the dedication and endurance that’s required to make important art.