Edward Weston Photographs

Two photographs complete museum’s holdings of artist’s oeuvre

Two photographs by pioneering modernist Edward Weston, Pyramid of the Sun, Teotihuacan and Heaped Black Ollas, provide a critical piece of the narrative of 20th-century photography: the transition made by this key artist from pictorialism to modernism. Weston is well represented in the museum’s collection by a pictorialist portrait from 1915 and 11 modernist images from the 1930s and 1940s. But it was in Mexico between 1923 and 1926, where these two photographs were made, that his stylistic shift occurred, a period previously absent from our holdings. These prints have an impressive provenance. They were originally in the collection of Anita Brenner, a scholar of Mexican culture and history who commissioned Weston in 1925 to provide photographs to illustrate her book, Idols Behind Altars. The project prompted him to delve deeply into the country’s pre-colonial monuments and its contemporary art and crafts.

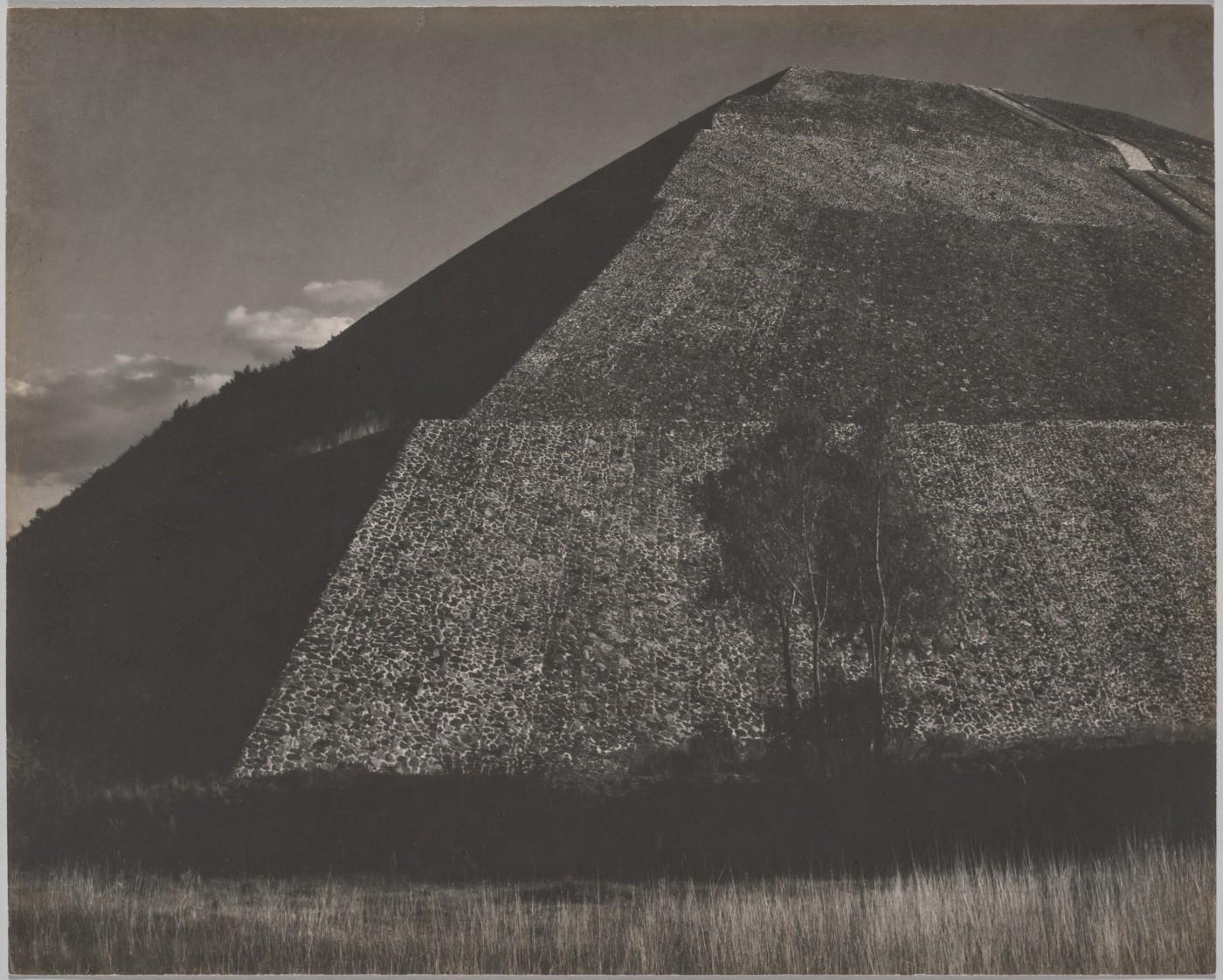

Pyramid of the Sun, Teotihuacan depicts the third largest pyramid in the world, but differs from standard travel and tourist views of the site. Weston chose to photograph the structure from an angle that emphasizes its geometry and massiveness. His goal is not to describe a building but to inspire awe, to convey the pyramid’s majesty and monumental scale. In his image, human achievement dwarfs nature, represented here by three lacy trees, some ground vegetation, and a glimpse of the sky.

The choice of angle, framing, and dark moodiness of the print are intended to evoke an emotional response, a sense of the dramatic that was characteristic of much pictorialist work. Its composition is fully modernist. The triangle of the pyramid traverses the entire height of the frame, and two horizontal stripes of vegetation hide the structure’s base. This powerful geometric division of space emphasizes the flatness of the picture plane.

Pyramid of the Sun, Teotihuacan is also modernist in its seeming lack of manipulation to print or negative. Many pictorialists used handwork on the print or negative to distance their depictions from the literal recording of reality. The lack of manipulation reflects Weston’s newfound devotion to photography’s ability to record the external world.

Weston made Heaped Black Ollas in 1926, when he had become a full-fledged modernist and was enamored of the genre of still life, then new to him. While at a market, Weston converted a haphazard heap of pots into a tightly framed, rhythmic composition that alternates brightly lit, volumetric spheres with dark, flat circles. Instead of staging the work, a trait characteristic of pictorialism, he added a new way of working to his repertoire: interpreting life as he found it.