The Museum of Modern Art’s Charles White: A Retrospective, on view from October 7, 2018, through January 13, 2019, is the first major exhibition dedicated to Charles White (1918–1979) in over three decades. Organized chronologically, the retrospective charts the entirety of White’s career, illuminating his socially motivated responses to the tumultuous events and cultural episodes that defined 20th-century American history. The exhibition’s roughly 100 drawings, paintings, and prints, along with additional ephemera, attest to White’s continually developing body of work, and serve as a model for the active role art can play in contemporary society. Charles White: A Retrospective is organized by Esther Adler, Associate Curator, Department of Drawings and Prints, MoMA; and Sarah Kelly Oehler, Field-McCormick Chair and Curator of American Art, The Art Institute of Chicago. The exhibition was on view at The Art Institute of Chicago from June 8 through September 3, 2018, and following its MoMA presentation it will travel to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), where it will be on view from February 17 through June 9, 2019.

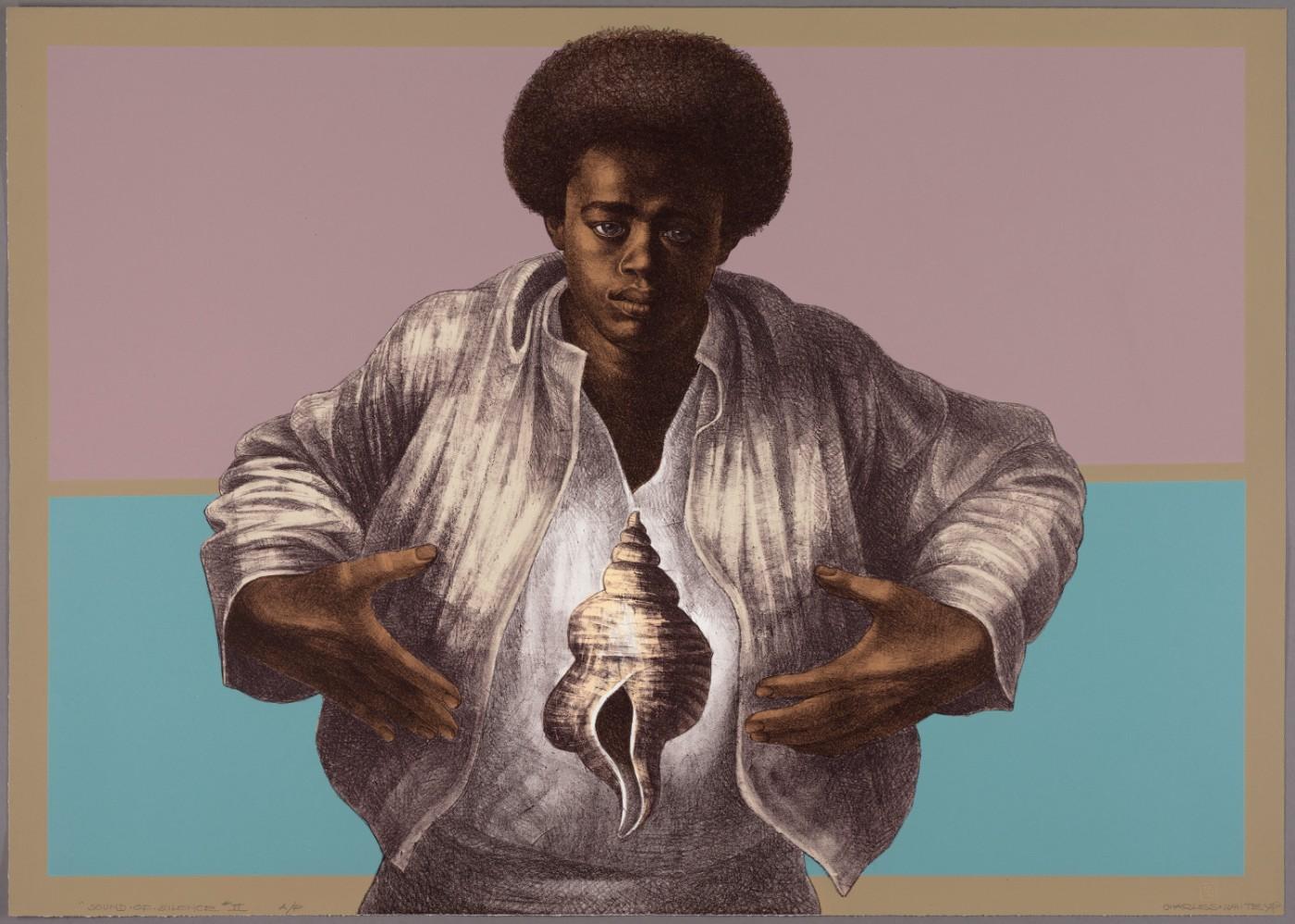

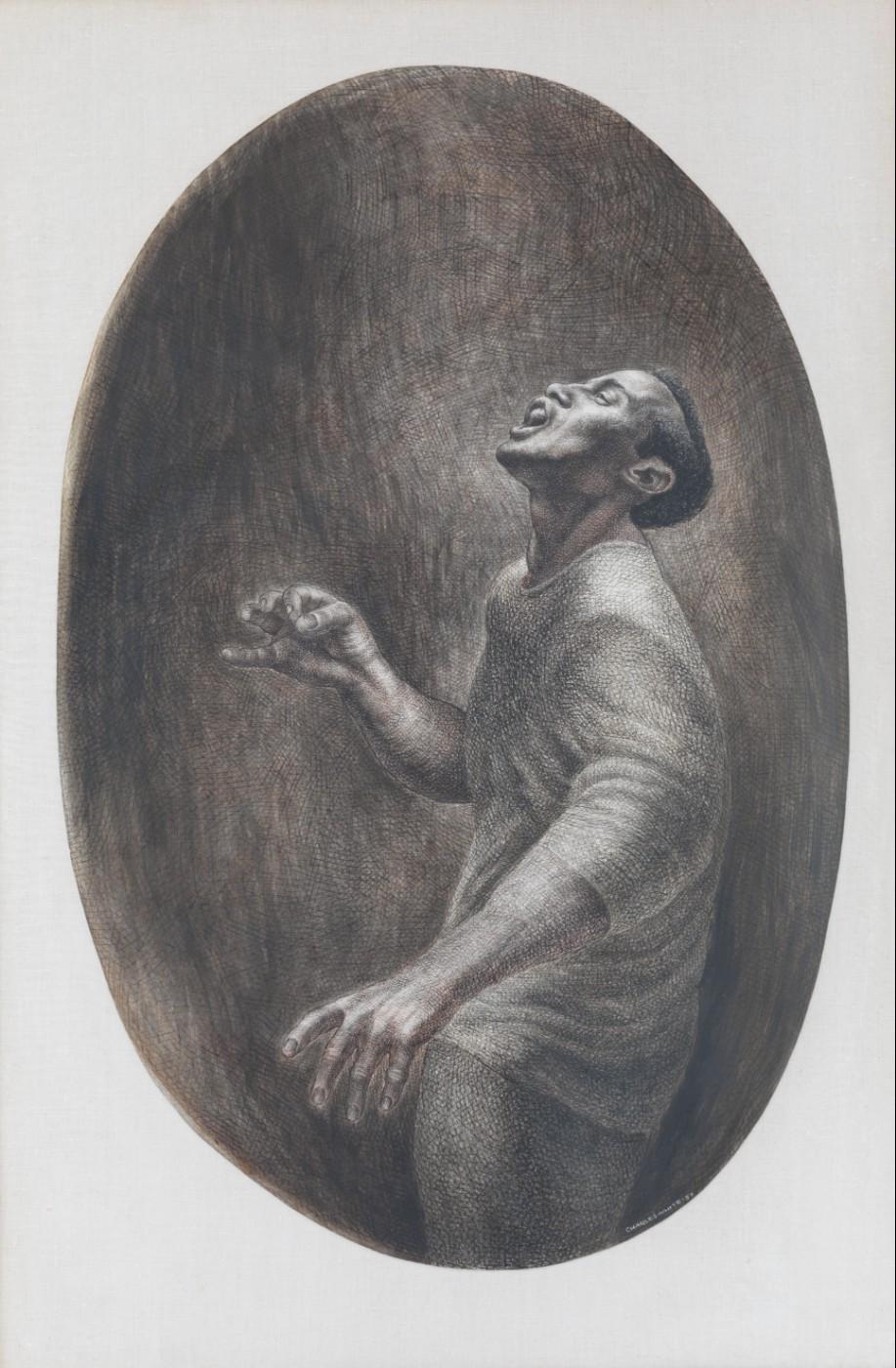

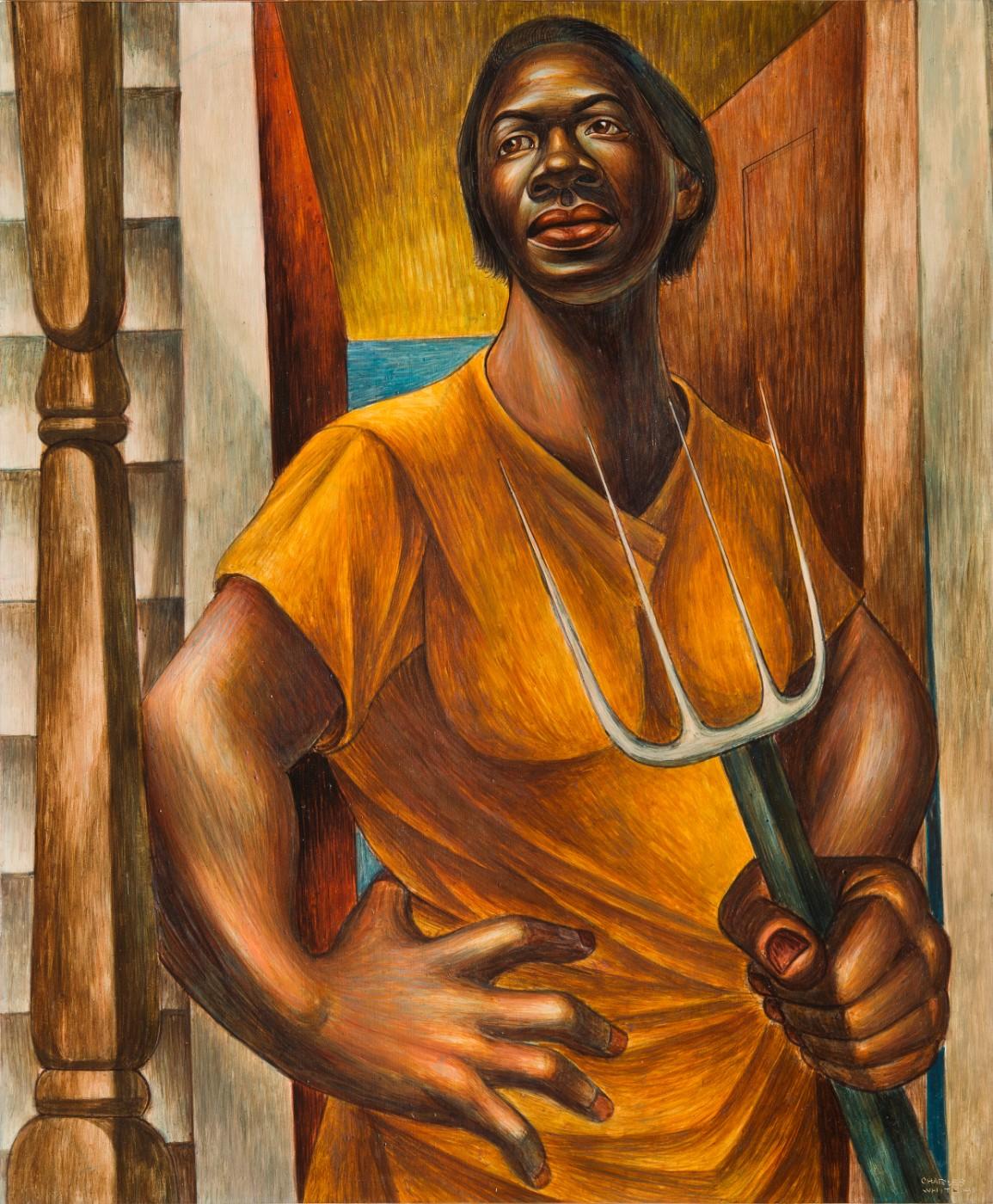

The exhibition includes representative work from the three artistic centers in which White lived, created, and taught throughout his life: Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles. It begins with early paintings and murals White made for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in Depression-era Chicago, where he grew up. Shortly thereafter, between 1942 and 1956, White lived mainly in New York City, teaching drawing, exhibiting at the progressive ACA Gallery on 57th Street, and supporting the Committee for the Negro in the Arts in Harlem. A selection of White’s personal photographs, also on view in the exhibition, capture his life in New York, while the inclusion of his work for album covers, publications, film, and television emphasize his dedication to more accessible distribution outlets for his art. The presentation concludes with the inventive output from his last decades as an internationally established figure and influential teacher in Los Angeles during the 1960s and ’70s.

A number of rarely exhibited key works from across White’s oeuvre are gathered for the first time, and are included exclusively in MoMA’s presentation of the exhibition. White’s first mural, Five Great American Negroes (1939), and the tour-du-force drawing Native Son No. 2 (1942) are on loan from the Howard University Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. Howard President Dr. Wayne A. I. Frederick said of the historic loan, “The Howard University Gallery of Art is honored to loan two significant Charles White works from our collection to The Museum of Modern Art. Mr. White left an indelible mark on Howard University, having served as an artist-in-residence in 1945 and as a distinguished professor in 1978. The two pieces that will be on display demonstrate his ability to capture the mood of a generation.” Two other seldomseen masterpieces, Mahalia (1955) and Folksinger (Voice of Jericho: Portrait of Harry Belafonte) (1957), are on loan from the collection of Pamela and Harry Belafonte—the latter of whom was a close friend and collaborator of White’s.