Robert Huot (born 1935) has been an artist and politically engaged citizen for much of his life. By his early 30s, he had established himself as an active player in the New York City art scene. He was a serious painter of large, minimalist canvases that were critically well received; he exhibited regularly at commercial galleries in New York and in Europe; he collaborated with his peers, including artist Robert Morris and choreographer Twyla Tharp, his first wife; and he was invited to participate in notable exhibitions at the Guggenheim Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. By art world standards, Robert Huot was a success.

By the end of the tumultuous 1960s, Huot grew increasingly disenchanted with the art world, its commercialization, and its seeming obliviousness to volatile issues of the day, particularly the United States’ war with Vietnam. As a member of the Art Workers Coalition, he actively protested the war and other injustices, but Huot describes his art and life at this moment as a disappearing act: his paintings became conceptual and ephemeral, and he moved from New York to an upstate farm in rural Chenango County.

Huot stopped painting traditional, rectangular canvases but he remained an creative force, making films; producing an impressive body of work known as the Diary Paintings; performing with his band, the Chameleons; and collaborating with artist Carol Kinne, his wife, on a variety of artistic and political projects; all the while commuting weekly to teach at Hunter College.

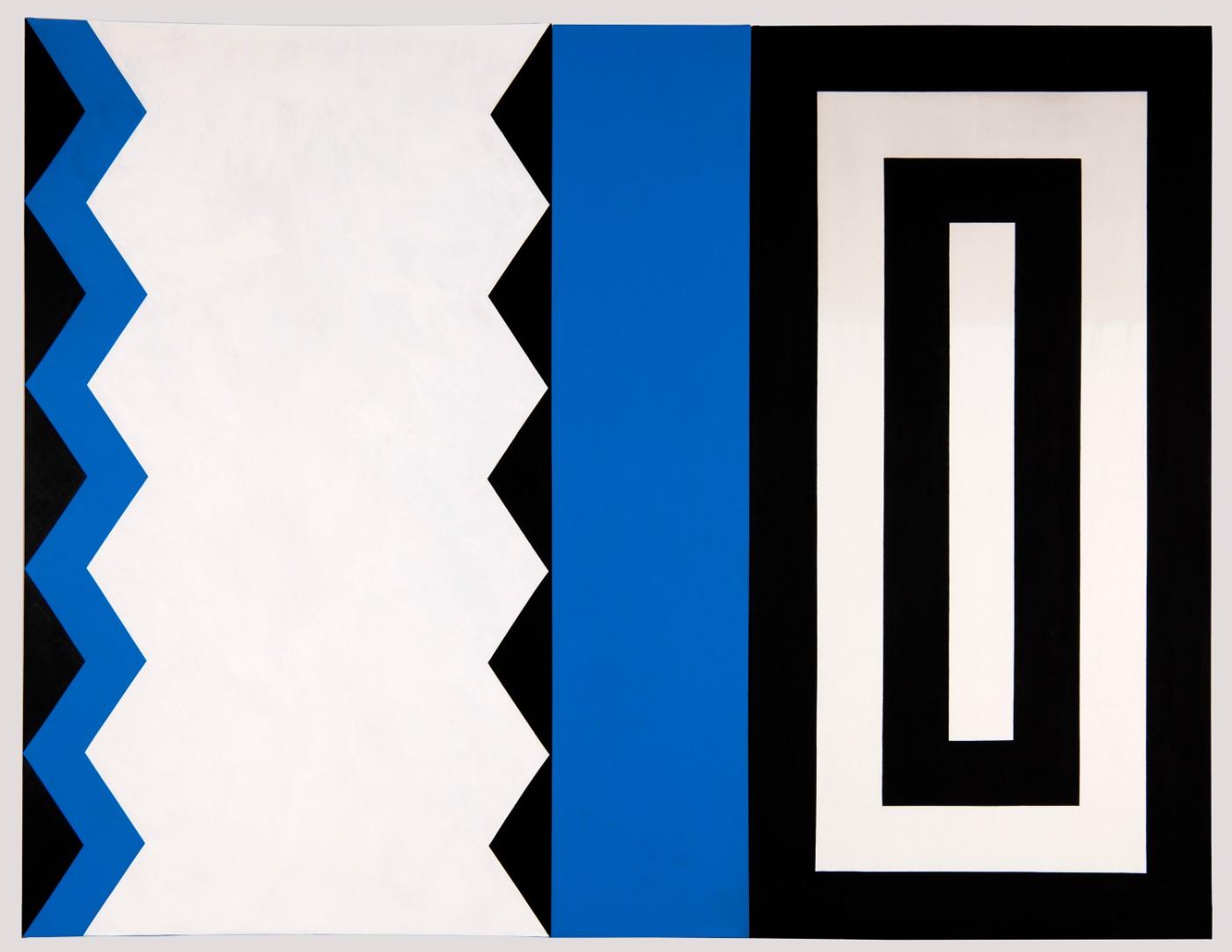

Robert Huot Paintings includes major, representative works from all eras of his career. His early paintings, such as Chriss, 1964, demonstrate Huot’s ability to create a dynamic, active composition with a minimal palette and few forms. Shear, 1963, disrupts the expected single plane of a painting’s surface by shifting the vertical painted bands in relation to the actual line where the works’ two panels meet. By the middle of the 1960s, Huot was preoccupied with uniting his paintings with the wall. He experimented with several kinds of solutions, including using rounded stretcher bars in works such as Silver Kiss, 1968. In the same pursuit, Huot created a series of works made of translucent nylon stretched over silver-painted bars, saying, “The nylon took the painting’s clothes off and let the wall show through.” By 1969-70, Huot had abandoned object-making for filmmaking and conceptual art.