As a classical technique, ink painting has long been distinguished by certain conventions. But beginning in the 1950s, Suh Se Ok began adapting the elements of what is known as “literati painting” called Muninhwa, derived from calligraphy and poetry and traditionally practiced by noble scholars. In this approach, Suh Se Ok developed a new, progressive and abstract visual language that refused the modernist spirit of heedless novelty in favor of one that also embraced and expanded on historical precedent. Suh Se Ok’s initial approach to the medium was then disruptive, but was also marked by great sensitivity and intelligence. Neither was he alone in his emphases; in 1959, he formed a group called the Mungnimhoe, or Ink Forest Society, which strived for unique styles of experimental ink painting that had its roots in literati painting.

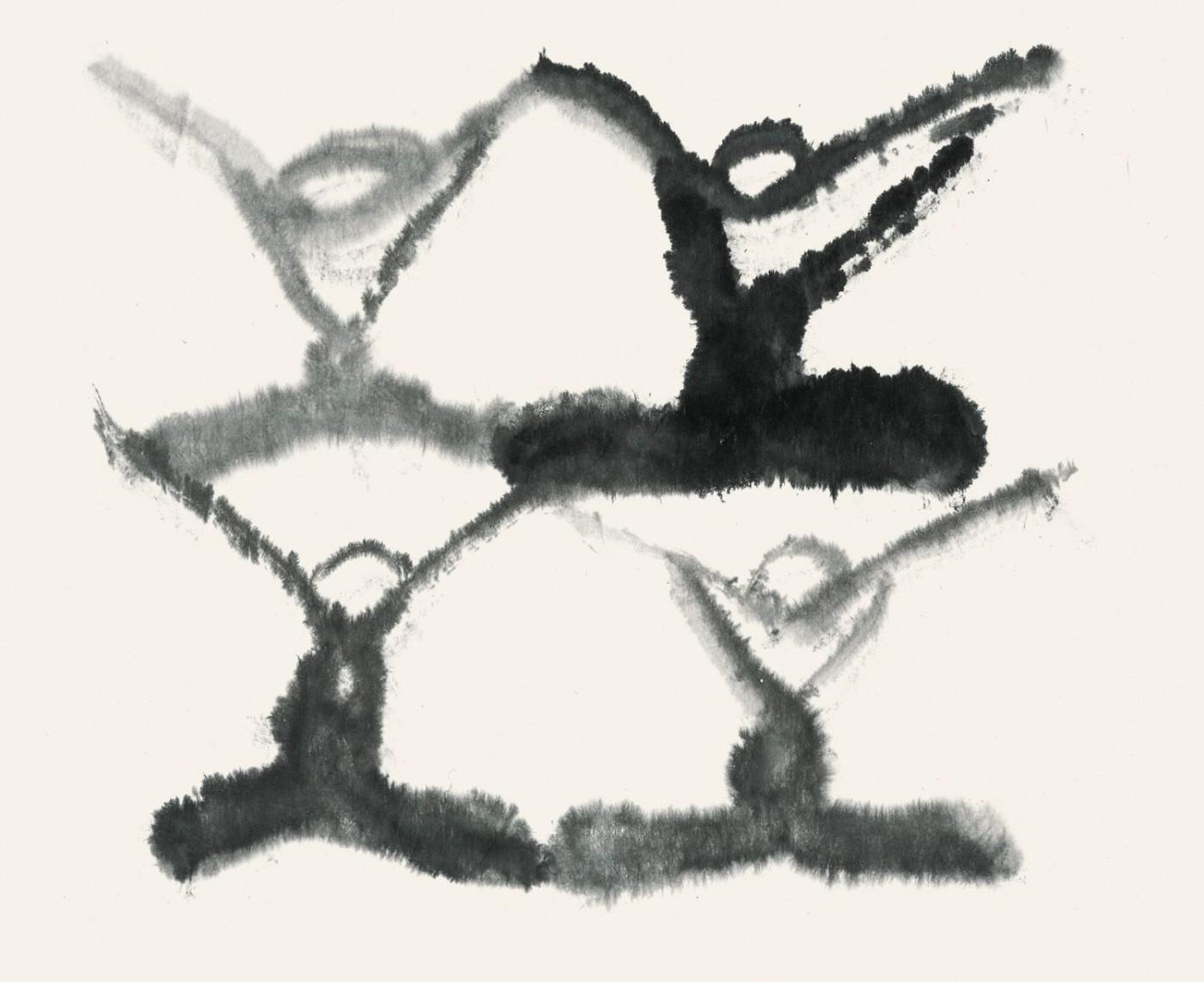

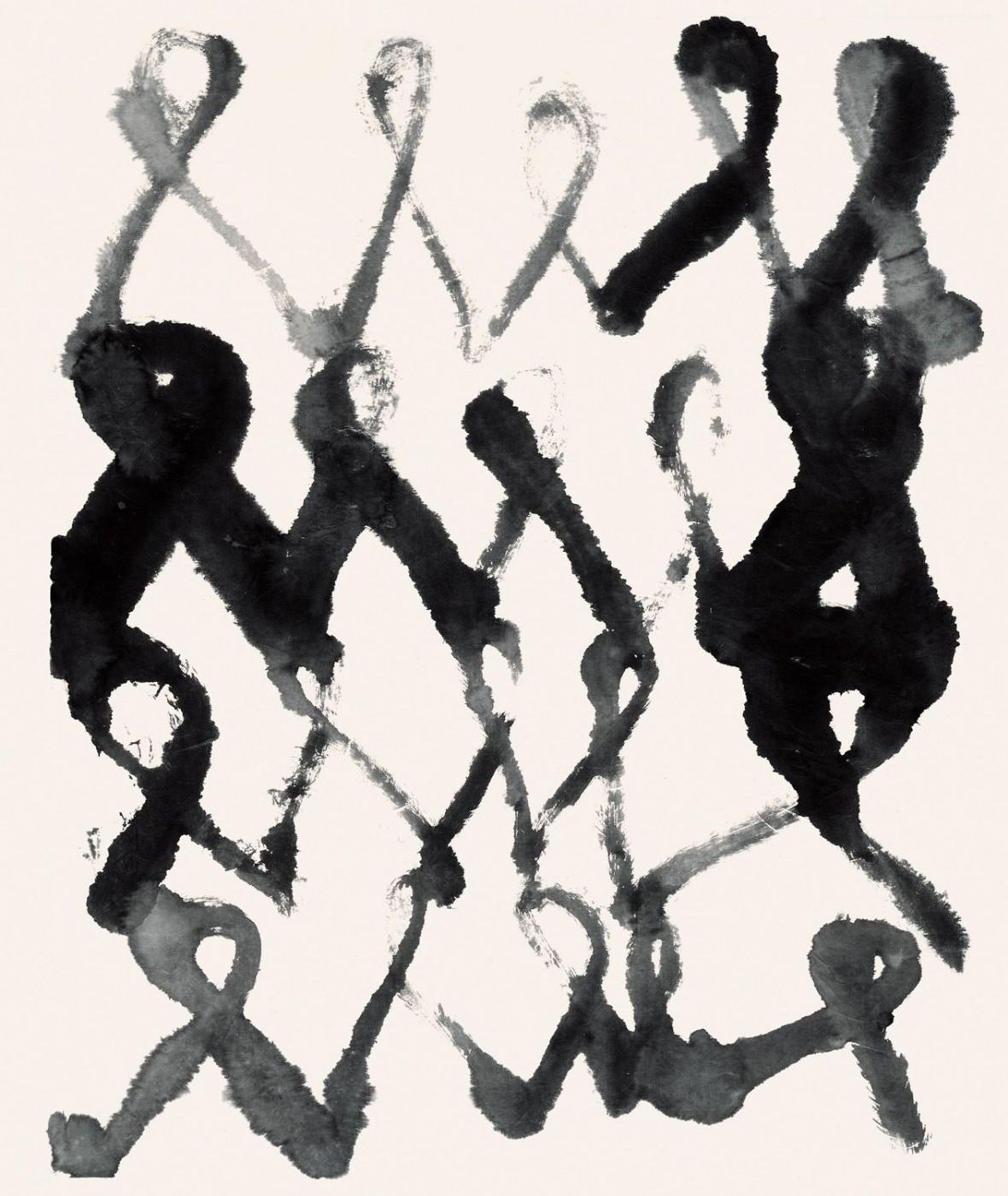

Stripped of all color, detail, and perspectival space, the radically restricted painterly practice that Suh Se Ok and his contemporaries developed allows for a broad range of interpretation. His paintings occupy the border between figuration and abstraction, and while the People series in particular clearly references the human form, the artist has also characterized the works as alluding to “shadows on the stage of life” (in Korean, geu-rim-ja)—its ordinarily invisible pains and pleasures. Some of his images also exhibit a similarity to Korean ideographs; as an erudite literati painter raised in a family of classical scholars, Suh Se Ok is an accomplished philosopher, poet, calligrapher, and seal engraver. There is even a political element to his works’ stark appearance—Suh Se Ok and the other Mungnimhoe artists grew up under Japanese occupation, and initially regarded their confrontational vision as an explicit challenge to the traditional Japanese nihonga painting dominant at the time.

Visually, while Suh Se Ok’s technique and medium are outwardly simple, the artist manages to produce a surprising variety of marks, while also allowing ink’s inherent qualities to guide his hand. Though his works of the 1960s often make use of the liquid’s tendency to spill and spread across the paper, those of the following decade reveal the artist’s increasing focus on planning and control, as well as an absorption in the potential of negative space. “I paint the forms that I find in the infinite space beyond objects,” he has stated. “What is there and what is not there are in a constant cycle.” In this, they also share a sensibility with the Zen painting of artists such as Mu-ch’I and Bada Shanren.