In 2023, we covered exhibitions around the world from the much anticipated reopening of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, to Barkley Hendricks at the Frick and the Made in L.A. biennial at the Hammer Museum. We also covered topics that fascinated us such as our story on how art is proven to help brain health and how the Nazi's PR campaign for Hitler came crashing down when photographer Lee Miller posed in his bathtub. As you review the year in your preparation for making a fresh start in 2024, we hope you enjoy this selection of our favorite stories of 2023.

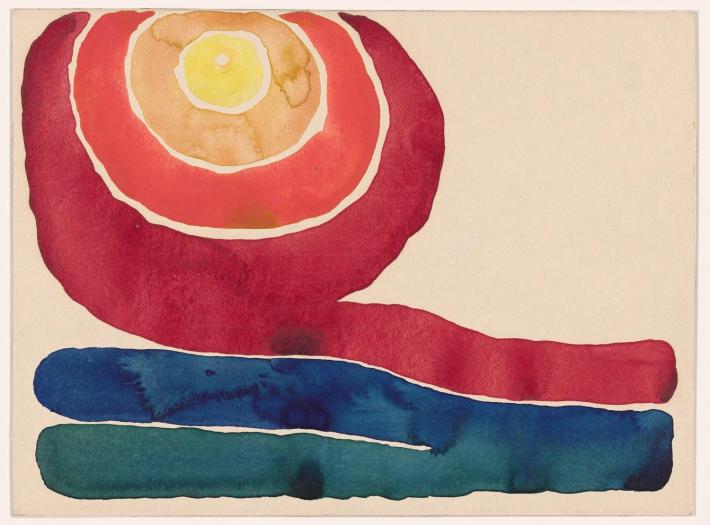

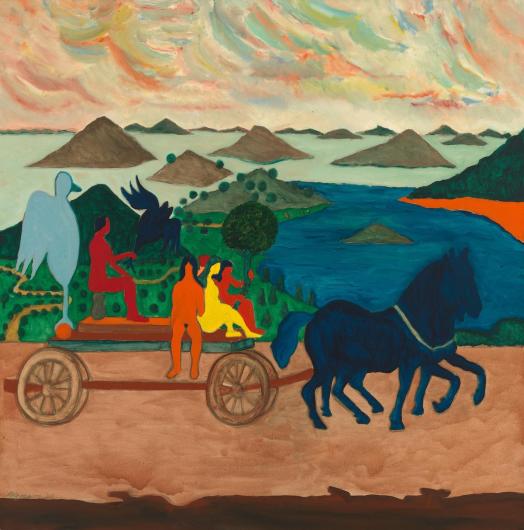

In 1915 when Georgia O’Keeffe was 23, she realized that everything she’d been taught in art school was of little value to her. Even though she had learned how to use art materials as a language, she had not found her own voice. She wanted to strip away what she’d been taught and start over. It was then that she wrote to her friend, Anita Pollitzer: “I began using charcoal and paper and decided not to use any color until it was impossible to do what I wanted to do in black and white.” It was eight months later when she first added a color: blue.

—Dian Parker

Image: Georgia O’Keeffe. Evening Star No.III, 1917. Watercolor on paper mounted on board. 8 7/8 x 11 7/8″ (22.7 x 30.4 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Mr. and Mrs. Donald B. Straus Fund, 1958.

Since its founding in the 1980s, the collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) has been one of the best kept secrets in Washington, D.C. As legend has it, the museum’s founder Wilhelmina Cole Holladay began collecting women artists in the 1970s after an auspicious visit to the Prado Museum. Traveling with her husband, Wallace F. Holladay, the couple came across works by Clara Peeters, an artist with whom they were not familiar. Arriving home, Wilhelmina ran to H.W. Janson’s History of Art to look up her discovery but couldn’t find Peeters—or any other woman artist—listed in that revered tome.

—Kathleen Cullen

Image: Installation view of the reopening exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts

A talented painter of eye-catching figurative pictures, Anna Weyant paints portraits and still lifes as convincingly as the Old Masters yet with the irony of the best Pop artists. Inspired by the painters of the Dutch Golden Age, Modernist masters, and contemporary art stars—as well as movies, music, novels, and children’s books—Weyant filters her influences through her mental and visual sieves to create charming canvases ripe with dark humor.

—Paul Laster

Image: Anna Weyant, detail of Loose Screw, 2020. Oil on canvas. 48 x 36 x 1 inches (121.9 x 91.4 x 2.5 centimeters).

In a letter on June 5, 1940, Edward Bernays wrote to Henry Luce, owner of Life magazine, advising him against publishing a puff piece on Adolf Hitler. Bernays warned, “America is prone to hero worship,” and “if Hitler should be successful [in his plans for war and genocide] it may be with our admiration for success, a man may well turn a present hate into admiration.” In other words, Life Magazine should not make a hero out of this individual.

—Rebecca Schiffman

Image: David E. Scherman, Lee Miller in Hitler’s bathtub.

Born in Concord, New Hampshire, [George] Condo studied art history and music theory at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. After graduating he moved to Boston and took a job in a silk screen shop while pursuing painting and drawing, and playing bass in the punk band, The Girls. In 1979, they played Tier 3, a downtown nightclub in Manhattan. The opening act was a band called Gray, featuring an unknown artist named Jean-Michel Basquiat. The two became fast friends and Condo moved to New York.

Among his first jobs in the city was a menial position at MoMA from which he was soon fired. His writing skills got him employed at Andy Warhol’s Factory where he eventually put his screen printing skills to work for slave wages under brutal conditions. Within a few years, Warhol was purchasing works by Condo and even took a photo of him, never realizing he used to be an employee.

—Jordan Reife

Image: George Condo and Hans Ulrich Obrist, installation view of "George Condo. People are Strange" at Hauser & Wirth West Hollywood.

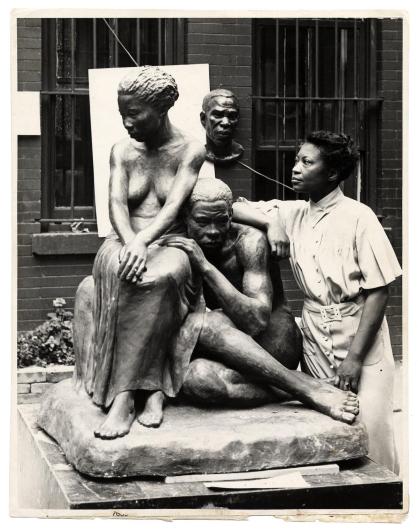

Acclaimed American sculptor, activist, and arts educator Augusta Savage (1892—1962) was a central figure in the Harlem Renaissance who fought for equal rights for African American artists and inspired future generations as a teacher. An outspoken critic of the fetishized "negro primitive" aesthetic favored by the white art world, Savage beautifully sculpted her fellow African Americans with realism, humanity, and personality, combatting the stereotypical portrayals of the time.

—Megan D. Robinson

Image: Augusta Savage posing with her sculpture Realization, created as part of the Works Progress Administration's Federal Art Project.

Made in L.A. is the Hammer Museum at UCLA's much-anticipated biennial and also its temperature-check on the L.A. art scene. For this year's biennial, called Acts of Living, curators Diana Nawi and Pablo José Ramírez hope to spark a reparative conversation between community histories and collective isolation.

—Carlota Gamboa

Image: Jessie Homer French, Urban Coyotes, 2023

Do archaeological exhibitions always require a theme? Of course, there needs to be an overarching subject justifying and advertising why a selection of material has been brought together. Themes help to tell stories, create an argument, and give meaning to seemingly disparate collections of objects. The narratives constructed by curators allow items, especially mundane ones, to take on increased relevance by placing them in a broader context.

—Christopher Siwicki

Image: A bronze statue of a Roman magistrate in a toga, known at the Arringatore. From the 2nd century BC, Perugia

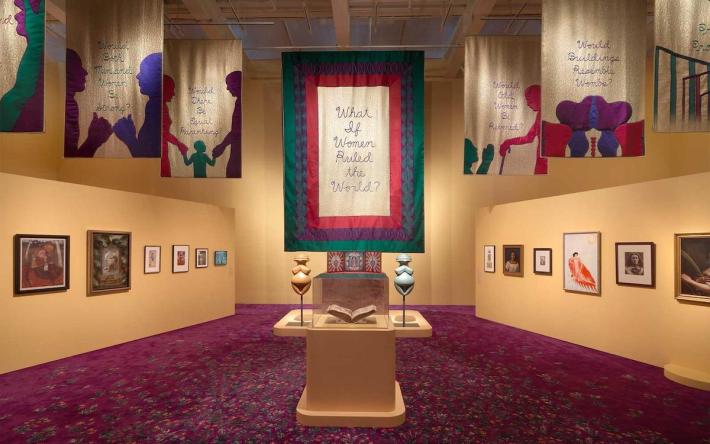

After six decades in the art world, Judy Chicago is finally getting her due. Her exhibition “Herstory,” currently on view at the New Museum, is the artist’s first comprehensive survey exhibition in New York.

Organized by the New Museum's ambitious curatorial team including Artistic Director Massimiliano Gioni, Gary Carrion-Murayari, Margot Norton (who is also Chief Curator at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Archive in California), and Assistant Curator Madeline Weisburg, the show, which has been extended through March 3, 2024, is a survey of Chicago’s work throughout various stages of her career. Ranging from the 1960s to a present day ongoing conversational project, the show looks at the role of feminism through the eyes of female and gender non-conforming artists who have largely gone under-recognized throughout the years. Intimately exploring Chicago’s oeuvre, the New Museum also houses an exhibition within an exhibition titled, “The City of Ladies” and features eighty artists ranging from the late Renaissance’s Artemisia Gentileschi, to Sojourner Truth, Dora Maar, and Leonora Carrington.

—Katy Hamer

Image: Installation view of Judy Chicago: Herstory at the New Museum

Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick, the Frick Collection’s overdue first solo exhibition of a Black artist and features fourteen large-scale portraits by Barkley L. Hendricks (1945-2017) meticulously selected by the Frick’s Curator Aimee Ng, and Consulting Curator Antwaun Sargent. Hendricks is known for his pioneering contemporary portraiture that depicted Black subjects in the traditions of the European Old Masters. Thus, the Frick Collection, with its iconic portraits by Rembrandt, Vermeer and Velázquez, is the perfect setting.

Art & Object sat down with Ng this month at The SisterYard cafe, in Frick Madison (the Frick Collection’s temporary home in the Breuer building), to ask what inspired the triumphant exhibition.

—Natasha Arora

Image: Installation view of Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick

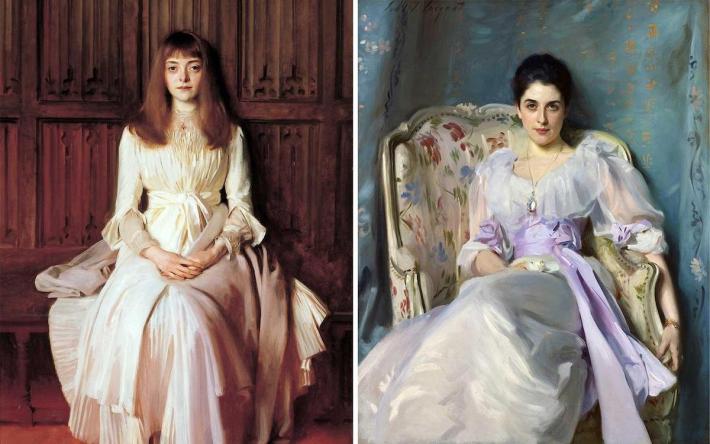

Sensual salmon-pink walls greet visitors in the first gallery of Fashioned by Sargent, the current exhibition at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston that pairs over 50 works by the much-loved American portrait painter John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) with actual garments worn by the elegant subjects in his paintings.

The color is a fitting backdrop for a single work, a full-length, standing portrait of Lady Sassoon (1907) displayed here alongside the flowing black taffeta opera cape she wore in the painting.

—Cynthia Close

The concept of gender has proven to be a tempestuous topic for decades now. Most recently, ideas around diverse gender identities and expressions have come under direct attack in parts of this country, with many heinous political schemes currently on the dockets meant to devalue and alienate the lived experiences of gender non-conforming individuals. At the core of these attacks is a particular unwillingness to appreciate or even tolerate other ways of thinking, being, and living that do not adhere to what many call “traditional” values. What those purporting said values do not wholly appreciate, however, is that there are many forms of what can or may be considered ‘traditional.’ Ideas by which certain groups govern themselves speak only to a minority of the global population and are in their ideological adolescence when compared to the entire breadth of human history and culture.

—Danielle Vander Horst

Image: Katheryn Winnick as Lagertha from the popular History Channel show Vikings. Characters such as Lagertha exemplify the modern fascination with Viking warrior women, also known as Shield Maidens. Though dramatized for TV by Winnick, Lagertha is thought to be a historical individual known mainly through Norwegian folktales and the Danish history written in the 12th century CE by Saxo Grammaticus.

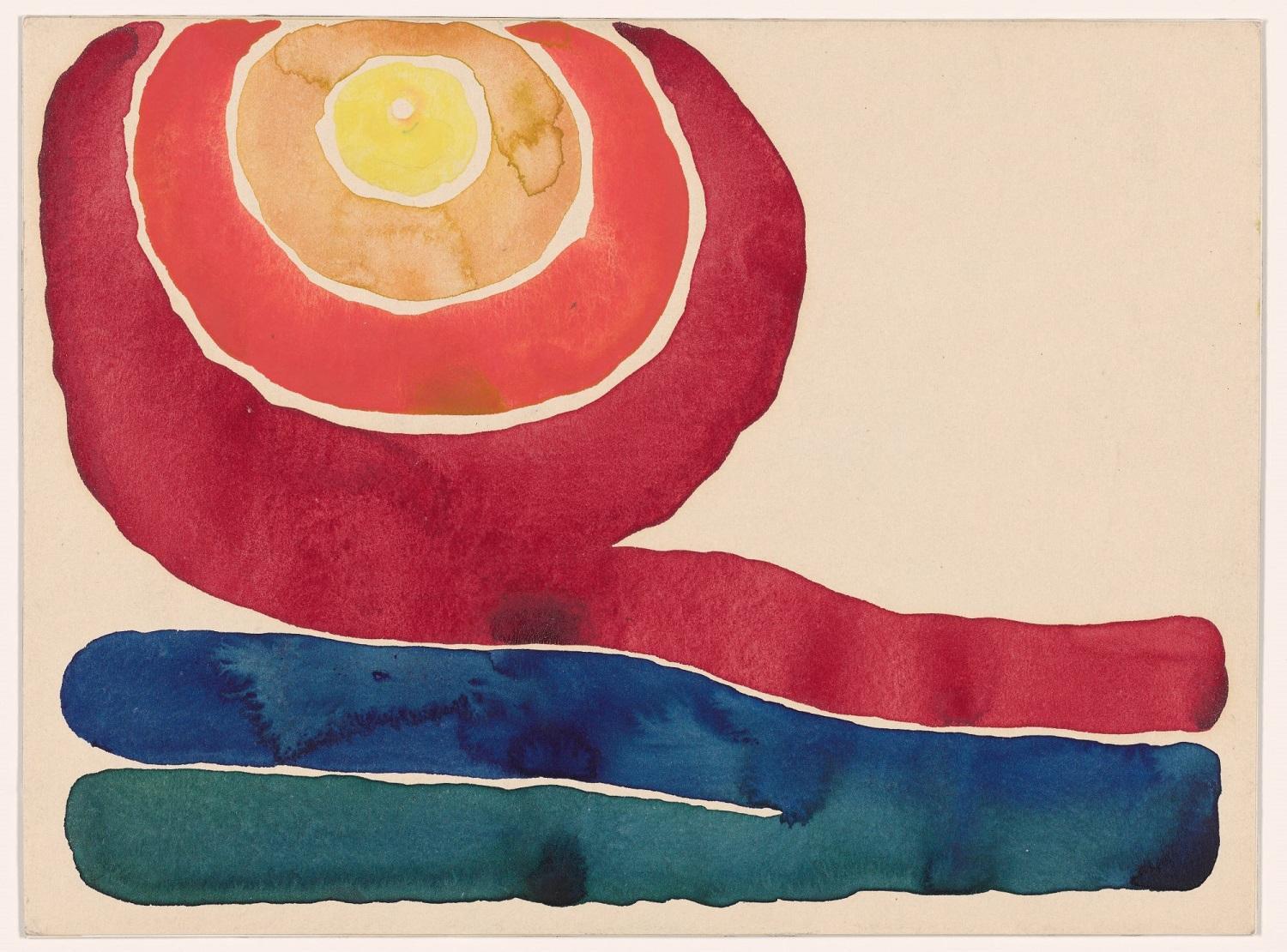

During the postwar era, movements were still a thing, and midcentury New York was the place where they were being minted. It mattered which program you were getting with, and in the late 1950s that still meant Abstract Expressionism, though Pop Art and Minimalism were waiting in the wings.

So, imagine how the work of painter Bob Thompson (1937–1966) would have fared. Figurative and focused on subjects adopted from European art history, it would have been out of place for any artist, let alone one among the few African Americans operating within a White-dominated environment.

—Howard Halle

Image: Bob Thompson, An Allegory, 1964, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

The SCAD Museum of Art in Savannah, Georgia is housed in a historic building that once served as a depot for the Central of Georgia Railway, the only surviving antebellum railroad complex in the United States. One very long gallery features a succession of archways along one side composed of Savannah Grey Brick, a unique over-sized brick dating to the 1800s that were hand-formed by enslaved people on a plantation called the Hermitage on the Savannah River. Along the other side of the gallery is a clean modern wall of windows.

It's against this backdrop that artist Tyler Mitchell’s exhibition, “Domestic Imaginaries” is staged. The exhibition features a showstopping 300-foot-long clothesline that starts at one end of the gallery and zig-zags clear through to the other end. From this meandering line, textiles of varying sizes and materials are hung with clothespins, each one featuring a photograph taken by Mitchell.

—Rozalia Jovanovic

Image: Installation view of Tyler Mitchell: Domestic Imaginaries

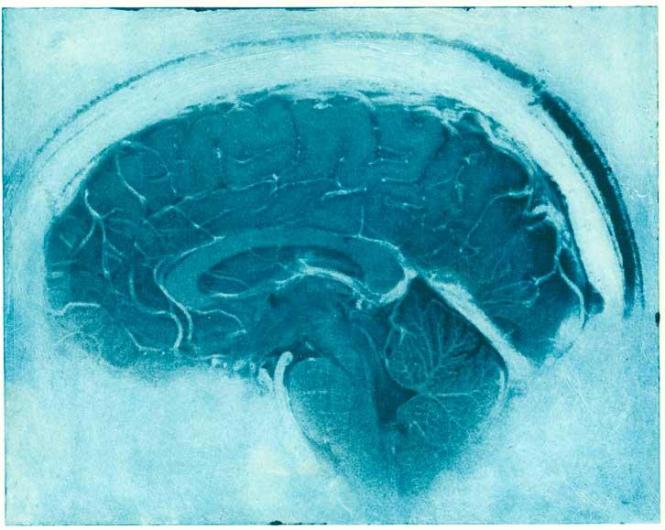

The mind-boggling, semi-new scientific field of neuroaesthetics may turn the art world on its head––in a good way. Emerging brain research proves what artists and art lovers have sensed all along: Art can make us feel better. But that’s only the beginning. There’s more, much more, to neuroesthetics.

“Neuroaesthetics emerged in the late 1990s, and nobody is clear on who coined the term, but a simple definition is that neuroesthetics is the study of how arts measurably changes the body, brain, and behavior and how this knowledge is translated into practice,” said Susan Magsamen, founder, and director of the International Arts + Mind Lab Center for Applied Neuroaesthetics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

—Colleen Smith

The Harlem Renaissance was an artistic and political movement that redefined Blackness in the United States as an act of liberation from post-antebellum discrimination and stereotypes, evidenced by Jim Crow laws and an abundance of blackface on-screen. Within this movement, Harlem in New York City served as the epicenter of Black philosophy, art, and music from the mid-1920s through the 1930s.

—Effie Jackson

Image: Jacob Lawrence, Harriet Tubman Series (Panel #4), 1940. Tempera on hardboard, unknown dimensions, Hampton University Museum, Hampton, Virginia.