Though in the west it is largely associated with yoga and sex, the practice and philosophy of Tantra is much more than that. Now the British Museum is delving into the rich, centuries-long traditions of Tantra, and how it has influenced cultures around the world and up to the present day.

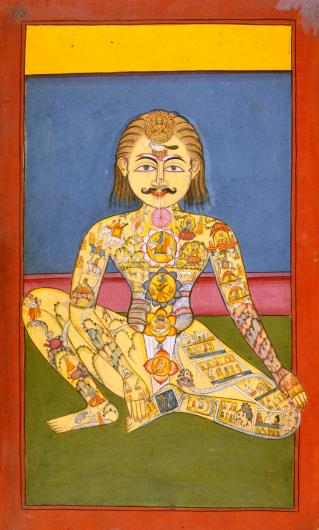

Page from Hatha yoga manuscript depicting the ‘yogic body’. India, early 19th century.

First emerging in India around 500 AD, the radical philosophy lead to major changes in religion, politics, and culture in India.

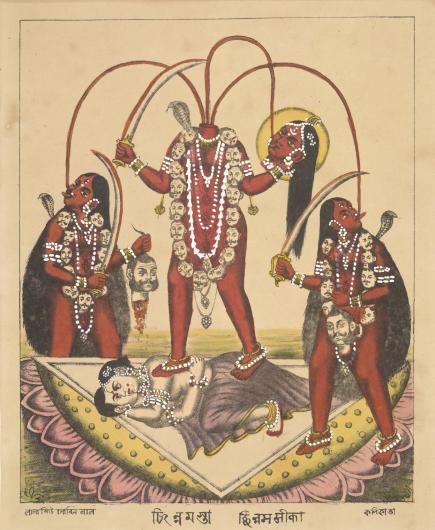

Chinnamasta, Lalashiu Gobin Lal, Kolkata, late 1800s.

The British Museum has one of the most extensive collections of Tantric art in the world, and this exhibition, which features over a hundred works, includes objects from India, Nepal, Tibet, Japan and the UK, from the seventh century AD to the present.

Chakrasamvara, Eastern India, 1100s.

According to curator Dr. Imma Ramos, “This major exhibition will capture the rebellious spirit of Tantra, with its potential to disrupt prevailing social, cultural and political establishments. Tantra is usually equated with sex in the West, but it should

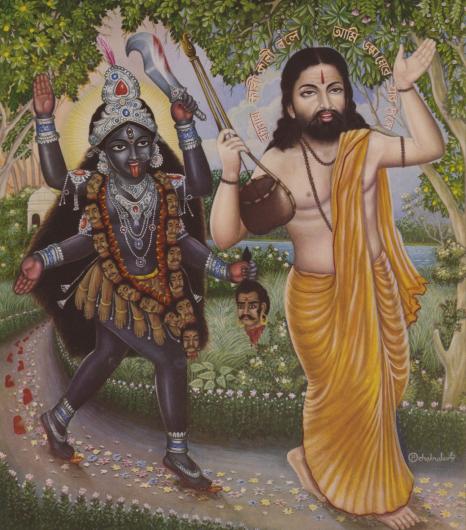

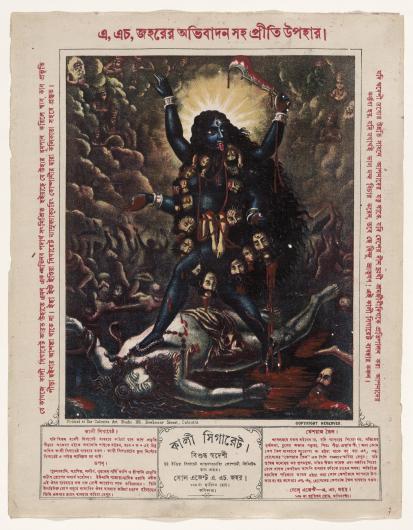

Kali striding over Shiva, probably Krishnanagar, Bengal, 1890s.

Tantra, which in sanskrit translate to ‘loom’ or to weave, in its sacred texts emphasizes the individual’s relationship with the gods, and that spiritual beliefs and practice are a divine conversation.

Ramprasad Sen and the goddess Kali, signed P. Chakraborty, Bengal, India, 20th century.

Through Tantric rituals, meditations, and visualizations, one could connect fully with the gods. These rituals, some of which included sexual practices and taking psychedelics, flaunted cultural taboos.

Chamunda dancing on a corpse, Madhya Pradesh, Central India, 800s.

Tantra was also trangressive in its emphasis on free will, the fact that each individual and their actions could be divine, and that one could achieve enlightenment and liberation on their own.

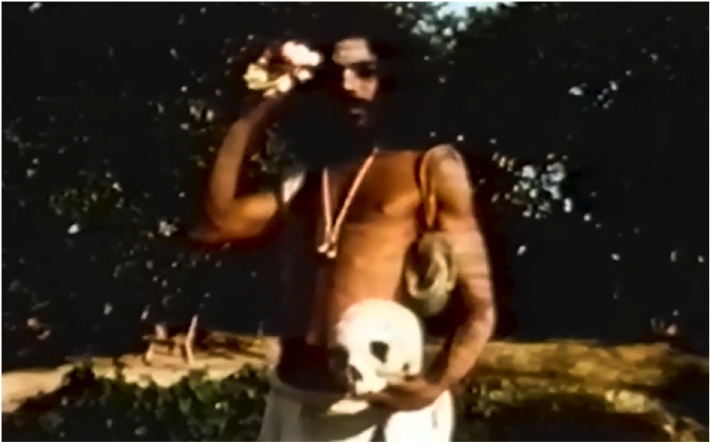

Still from Tantra: Indian Rites of Ecstasy, 1968, directed by Nik Douglas, co-produced by Mick Jagger and Robert Fraser (Ajit Mookerjee: consultant).

In the radical social revolutions of the 1960s, Tantra was a major influence. Free love, psychedelia, and a self-propelled spirituality were all elements of the counterculture that overlapped with or were inspired by Tantric practice and philosophy.

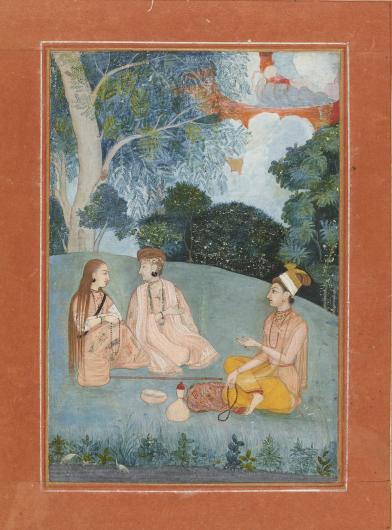

A woman visiting two Nath yoginis, North India, Mughal, about 1750.

Female goddess are particularly revered in Tantra, and this shift in philosophy opened up important spiritual roles that women were previously barred from.

Print depicting the goddess Kali, Calcutta Art Studio, Kolkata (Bengal, India), about 1885–95.

The goddess Kali is especially revered. A fierce warrior, she represents both death and rebirth.

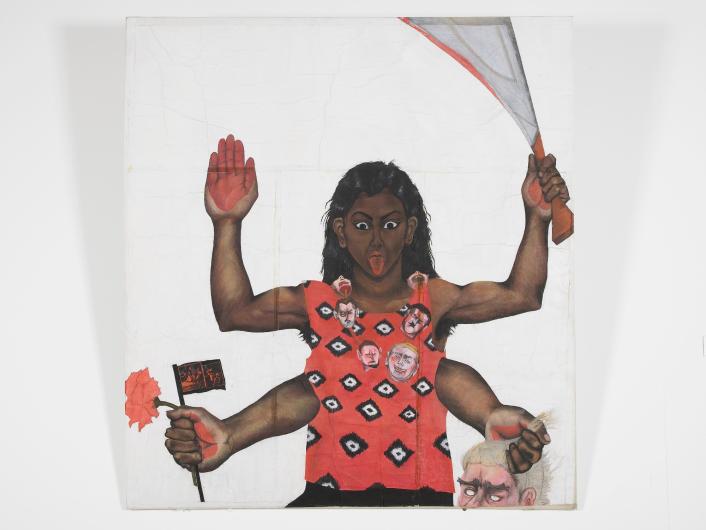

Sutapa Biswas, Housewives with Steak-Knives, 1985. Oil, acrylics, pencil, collage, white tape on paper on canvas.

Because of its focus on divine female energy and the worship of goddesses, Tantra has remained influential to modern day feminists and artists addressing feminist issues.

Bharti Kher, And all the while the benevolent slept, 2008.

More than a millennia after it's emergence, Tantra remains an influential philosophy that is present in the works of leading contemporary artists and thinkers like Bharti Kher.

Chandra Noyes

Chandra Noyes is the former Managing Editor for Art & Object.