NMWA’s building at 1250 New York Avenue, NW was originally constructed in 1908 as a Masonic temple (where women were not allowed entry) and the structure went through several iterations before the Holladays purchased it in 1985 and transformed it into the first museum in the world dedicated to women’s creative accomplishments.

It was also about this same time that activists began to scrutinize the collecting activities of work by women and marginalized artists in museums. Director Susan Fisher Sterling, who had started out as the museum’s curator, would approach galleries with the same question: “Do you have any women artists?”

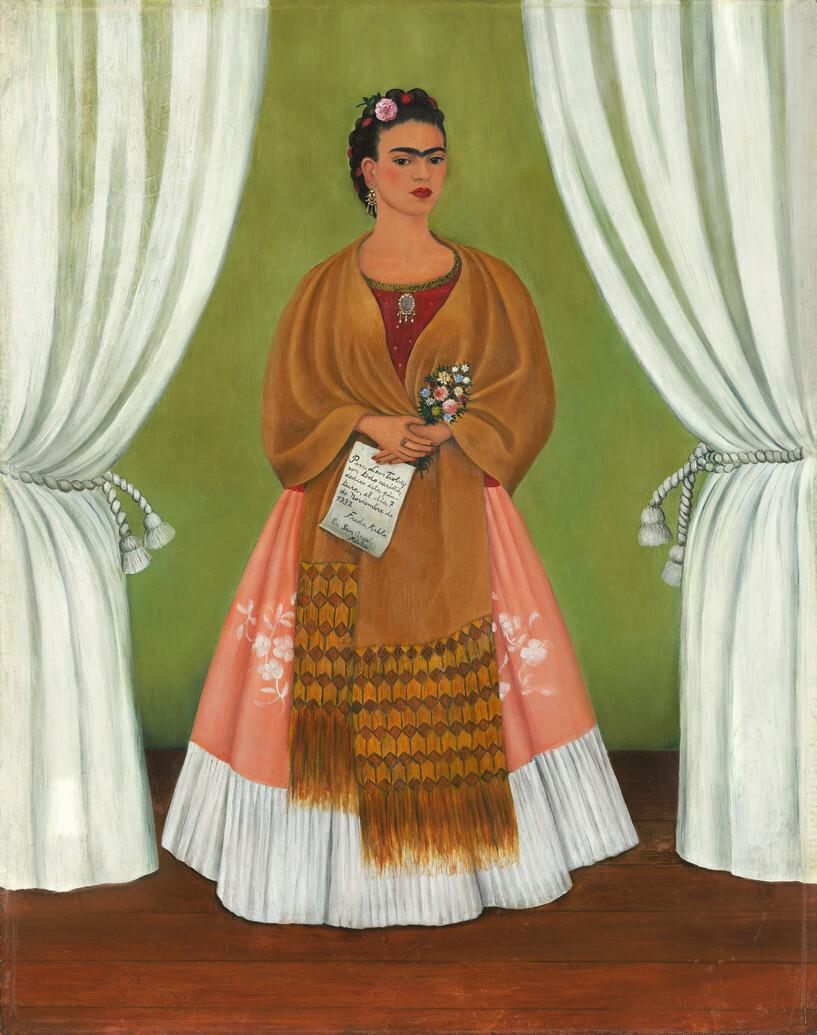

Initially, the Holladays donated a trove of 500 art objects that formed the foundation of NMWA’s collection, and rallied others to their cause. The recent renovation restored the building’s historical beauty while transforming its capabilities for the future—with expanded galleries and public spaces, improved educational facilities. The supporters of the collection include individuals, families, foundations, and the impassioned members of NMWA’s outreach committees—advocacy groups working around the world to promote the museum’s mission of artistic enfranchisement. Many works also have been donated by artists themselves, signifying their confidence in the museum as a steward of their legacies.

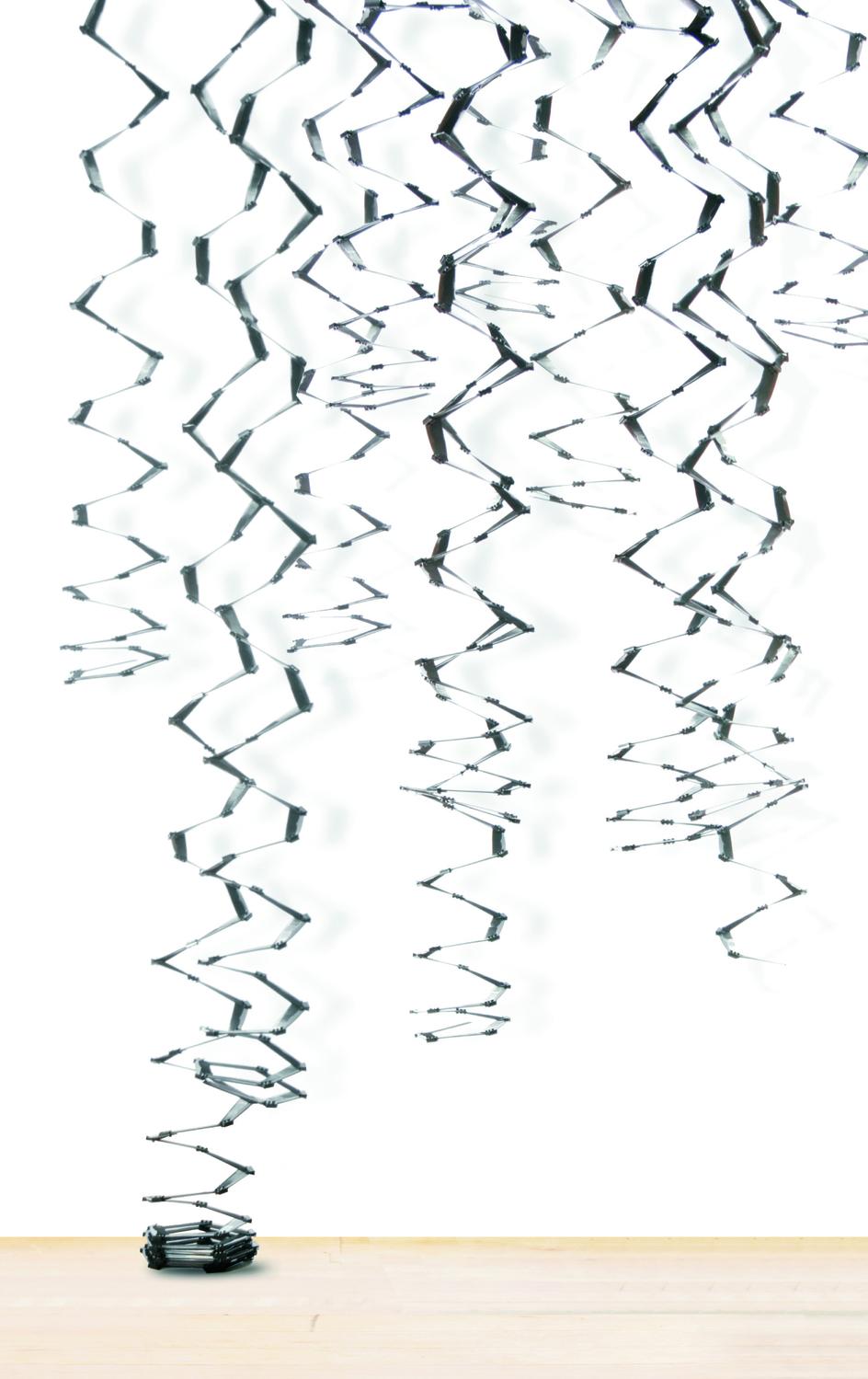

Holladay’s vision for the museum was elegantly embodied in the Great Hall. Now restored by the Baltimore architectural firm Sandra Vicchio & Associates, the building’s neoclassical proportions still speaks to the Georgetown establishment to which Holladay belonged. Visitors are greeted by the Murano glass chandelier that is a mixed-media assemblage by Joana Vasconcelos at the museum’s entry. Reclaiming the legacy of handwork among women makers, Vasconcelos’ chandelier with stuffed tube tentacles and crocheted puffs with beads and LED lights proclaims the centuries old legacy of handwork amongst women.