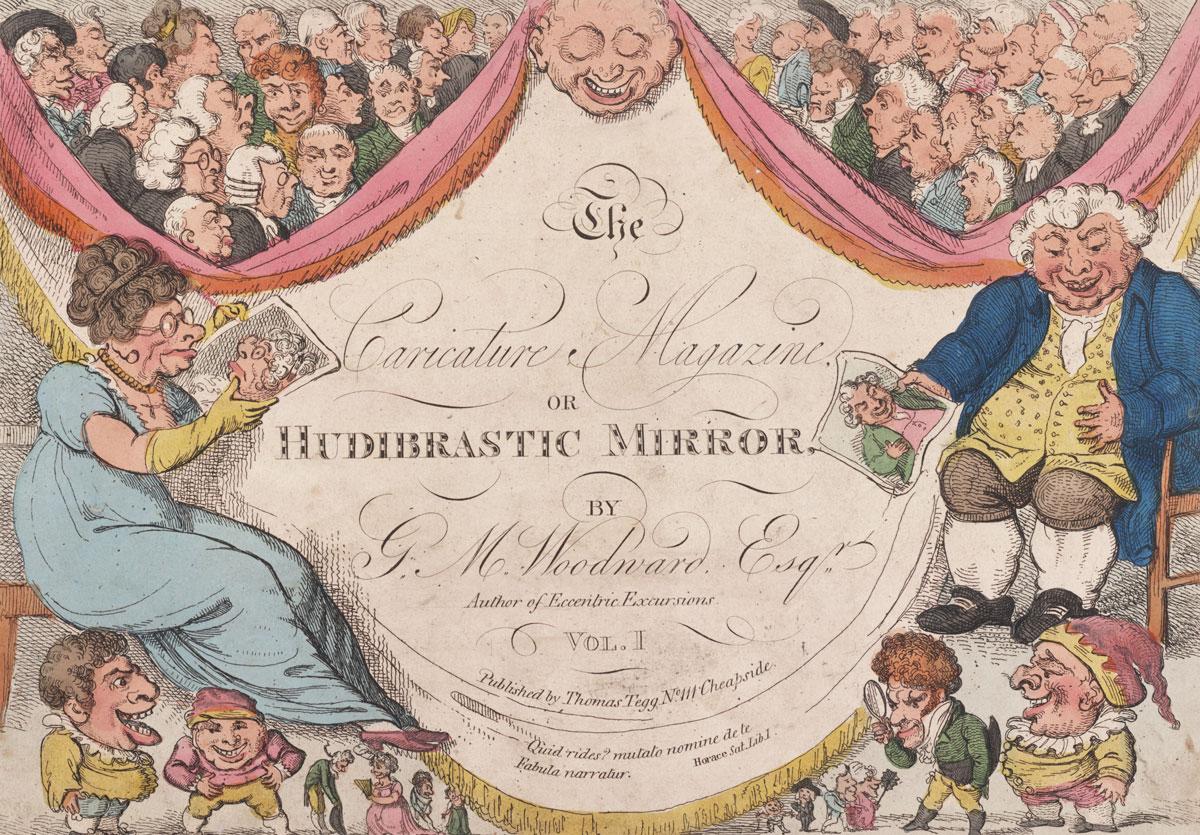

Among the many works on paper held by Yale University’s Lewis Walpole Library is a 1772 etching by Elizabeth Bridgetta Gulston titled A Character, which ridicules the social pretensions of a badly dressed courtier. In the lines of verse she inscribed below the image, Gulston wittily remarks, “Whene’er at Court he shews his Face/The Breeding Ladies Quit the Place.” Gulston’s print highlights the late Georgian fascination for observing, drawing, and collecting “characters.” Men and women of rank—like Gulston, a baronet’s daughter—as well as “middling” and lower-class British citizens reveled in the everyday spectacle of “characters” and “caricatures.” The terms were often used interchangeably in the period.

The Lewis Walpole Library, located in Farmington, Connecticut, about forty miles north of New Haven, features an extensive collection of eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century prints, drawings, paintings, rare books, and manuscripts; many of the library’s holdings originally belonged to Horace Walpole—he is the Walpole honored in the library’s name, while the Lewis part originates with twentieth-century donors Wilmarth Sheldon Lewis and Annie Burr Lewis. Like Joseph Gulston, Walpole was an avid collector of caricatures by the amateur artist Henry William Bunbury (Walpole praises Bunbury in his Anecdotes of Painting in England as a “second Hogarth”).

The exhibition Character Mongers, or, Trading in People on Paper in the Long 18th Century, at the Lewis Walpole Library from October 10, 2016, to January 27, 2017, highlighted these great works.