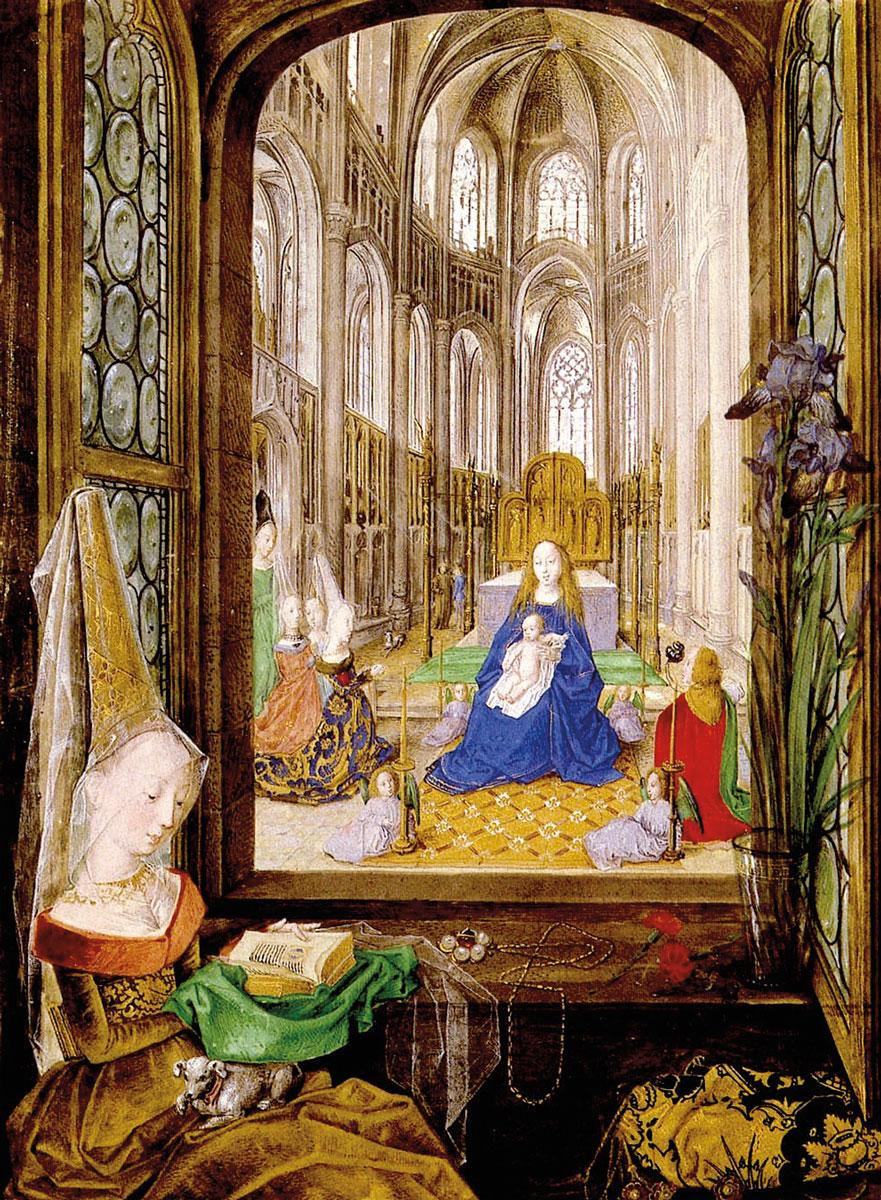

Throughout medieval Europe, hooded monks and nuns chanted prayers at these hours, making their devotions at dawn in chapel, between meals, before retiring to bed in the dormitory, and even while in town, with country bells tolling the changing hours. Sporadically from the thirteenth century and frequently by the fifteenth century, laypeople at home—kings and queens, princes and princesses, doctors, lawyers, schoolteachers, even tradesmen—began to use the Book of Hours to imitate monastic life as “armchair monks.” These treasured volumes were touched, kissed, cradled, admired, read from, scribbled in. They were often given as wedding gifts; they held family records of births, deaths, and marriages; they were used to teach children to read. It is not uncommon to find a Book of Hours that stayed in the same family through many generations, passing often through the female line, from mother to daughter. If a family owned one book, it was most likely to be a Book of Hours, treated as a cherished object. It is quite telling that, more often than not, Books of Hours were kept not in stately libraries or even upright on bookshelves, but wrapped up in velvet or precious textile and stored in boxes like jewelry, to be taken out on special occasions, shown to family and friends, carried about in the pocket to church or on pilgrimage. The Book of Hours was, simply put, a religious mainstay of family life—and, in many cases, an intimate witness to that life. Handling a Book of Hours today puts us in touch with the medieval past in a way that almost no other artifact can.

Central to most Books of Hours is an assortment of different texts and illustrations to which a buyer might request modifications or additions. Recited in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Hours of the Virgin is often illustrated with the Christmas story, made up of scenes from the early life of Christ. Other sets of daily readings include the Hours of the Cross and the Hours of the Holy Spirit. The afterlife loomed large in Books of Hours. Typically illustrated with an image of King David, the Penitential Psalms were recited to help one resist temptation to commit any of the Seven Deadly Sins (and thereby avoid the torments of hell). In a similar vein, the Office of the Dead was prayed to reduce the time spent by one's friends and relatives in the fires of purgatory. Prefacing each Book of Hours is a calendar listing the important feast days throughout the year, often enlivened by pictures of the signs of the zodiac and the Labors of the Months, activities that characterize a particular time of year. Suffrages, or prayers to special saints, were a common way of tailoring each book to its owner—someone might wish to include a prayer to Saint Margaret for a safe childbirth, or to Saint Apollonia for the happy resolution of dental problems, or to Saint Christopher for protection in one’s travels, and so forth.