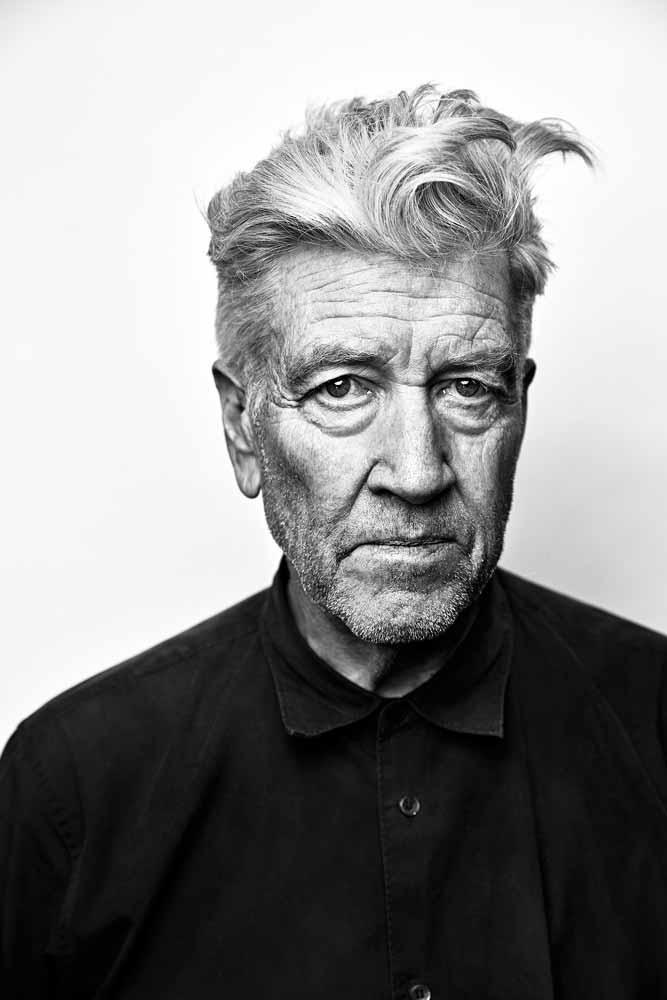

Is discord a sign of greatness? Many artists that are now celebrated, such as Caravaggio and El Greco, were at the time not appreciated by the critics nor their contemporaries. Called disrespectful and unorthodox, such artists were seen as rebels, freaks, and punks. In terms of punk, David Lynch has the hairstyle. The now white, wild, yet perfectly styled, familiar and comforting high riff is arguably the most recognizable feature of the American director. Born in 1946 in Missoula, Montana, David Lynch’s childhood years were spent moving around the United States to follow his father’s assignments as a USDA research scientist. Despite the frequent relocations, Lynch’s young life was the perfect example of 1960s America: “[it] was a dream world, those droning airplanes, blue skies, picket fences, green grass, cherry trees,” he recalled.

Always interested in the arts, Lynch began his career as a painter by enrolling first at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (he dropped out after a year in 1965) and then at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1966. During an interview at the Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane, Australia, in 2015, Lynch mentioned that the transition from painting to film happened one night. While looking at his unfinished painting of a garden at night, he first heard a wind coming from it and then saw the leaves moving. He realized: “Oh, a moving painting.” This epiphany was followed by his first short, Six Men Getting Sick (Six Times) in 1967, a four-minute short titled The Alphabet in 1968, and another short in 1970 called The Grandmother.

After moving to Los Angeles in 1971, Lynch began to work on his first feature-length film, Eraserhead, that would come out only in 1977. Despite initial rejections and negative press, the film has become a cult movie to the point that popular TV shows and cult classics, like Gilmore Girls, reference it. Eraserhead is important because it featured elements and symbols that since then have been recurring in Lynch’s cinematic universe: electricity, the outer space or void, deformed beings, dreams and the subconscious, and the importance of sounds and music as clarifying and leading elements in the storyline. After Eraserhead, Lynch directed The Elephant Man (1980), Dune (1984), Blue Velvet (1986), Wild at Heart (1990), and Mulholland Drive (2001). His 1990 series Twin Peaks changed television and us, as viewers, forever. The recurring line “The owls are not what they seem” is the core message of the series: the good and the bad, the shown and the hidden, time and space, are all variables that co-exist in the universe and in mankind.