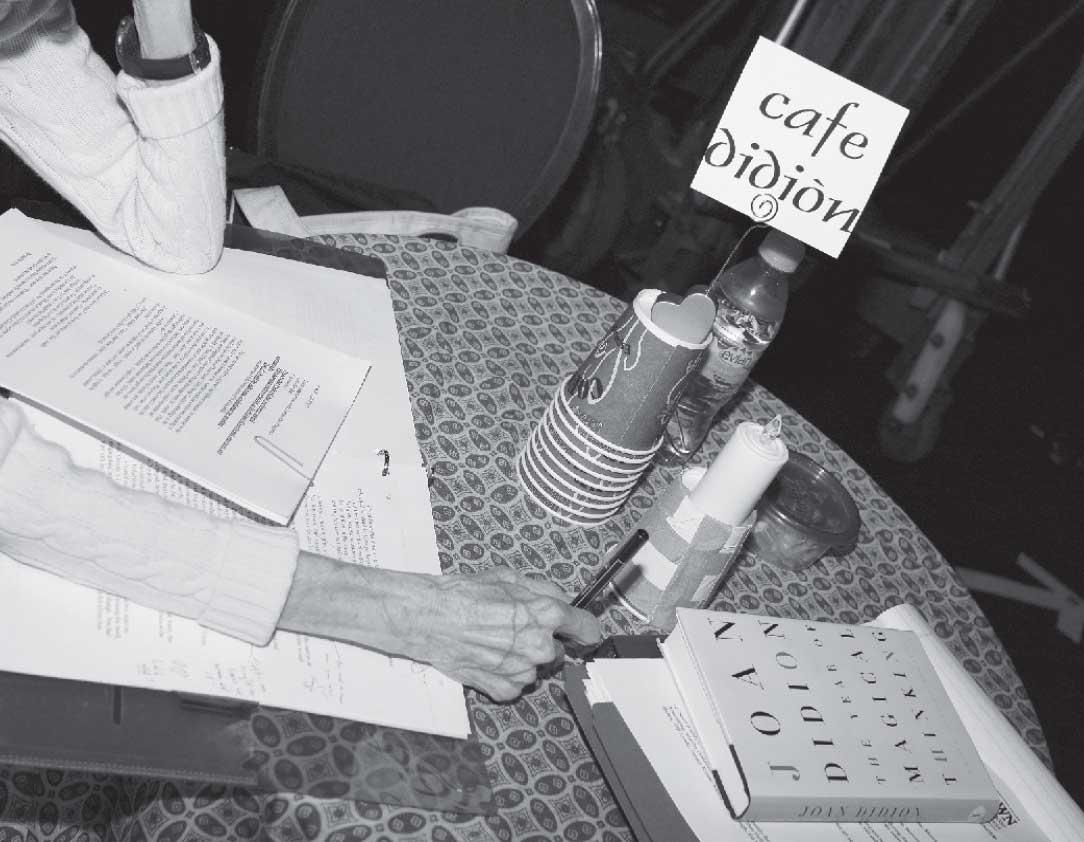

Most recently Als has curated a Joan Didion exhibition, What She Means, at the Hammer Museum in LA, running through February 19, then moving to the Perez Art Museum Miami. In our interview about the current Didion exhibit, Als told me, “I wanted to show the trajectory of and the developments of someone’s consciousness.” This intention saturates all of his work, including his teaching about queer writers like Thomas Mann, Carson McCullers, Dennis Cooper, Richard Wright, and James Baldwin who have all, as Als said, “produced a body of literature that increases our understanding of difference.”

This broad encompassing, contextualizing focus in all of his work can be summed up in his statement about the current curatorial climate. “There is altogether too much talk about the object as an isolated creation, separate from the world of its creator. Viewing art in this way undermines its power to teach us about empathy, about who we are or who we are not, in relation to an artist or to the world at large.”

Our conversation continued as follows:

Dian Parker (A&O): You have not been reviewing theatre for the New Yorker for many years but moved on to writing about a variety of other interests. For the last twelve years, you’ve curated a number of exhibitions for galleries and museums. Your current exhibition of Didion’s work, What She Means, as well as the past show about James Baldwin, God Made My Face, at David Zwirner, are parallel in how you pair their stories with visuals.

Hilton Als (Als): It’s a great opportunity to speak in another language. The visual has great import. The writing about the subject is a collaboration with the artist, whether alive or dead. I’m making atmospheres, environments to think about American culture in a different way. It is a gift as a curator to use their enormous words and ideas and to understand them as best I can. I give their words visual energy. Visual components speak to me.

A&O: You have the ability in your curation to crack through the fantasy of American culture, just as Didion and Baldwin were able to do in their writing. I see that same craft in the way you choose your images, how you are able to convey Didion and Baldwin visually.

Als: They were crafts people who were able to see without sentimentalizing their country. And to talk about where they were from; America, which they found troubled and troubling, but it was still their home. So much of what we see is commodified in the world. Things are pasteurized for easy ingestion. My first experience in museums as a kid was a Robert Rosenberg retrospective. It was a seminal moment not knowing what he was doing. There were docents then at MoMA. One of them explained the work to me. It was as if the top of my head blew off listening to her. That there could be a linguistic equivalent to the complications of the visual world. People need to use the same care with the text as with the visuals.

A&O: At the Met Opera in 2016, you curated “Desdemona for Celia by Hilton” with paintings by Celia Paul. In that exhibit it felt as if you were trying to erase the divide between the public and private self. The raw honesty and vulnerability in the paintings and what you revealed in the catalogue about fear, jealousy, and love with Desdemona, Othello, Celia, and yourself.

Als: It’s wild that you pointed that out. Dodie Kazanjian at the Met asked me to do a show about myself, to put myself forward. In my life I’ve always put other people first.