While the origin of kimono is unclear, it seems that the flow of people and goods between China and Japan during the Heian period (794-1185 CE) played a pivotal role in the birth of the modern-day kimono. The kimono, literally the thing worn, was worn by men and women alike. The embroidery, patterns, fabrics, and colors were used to differentiate between social classes, seasons, married and unmarried women, and social occasions. The kimono saw a decline in popularity at the end of the Meiji period (1868-1912 CE) as people were encouraged to embrace the more practical Western-style clothing. Nowadays kimono are mainly worn for special events, such as weddings and funerals.

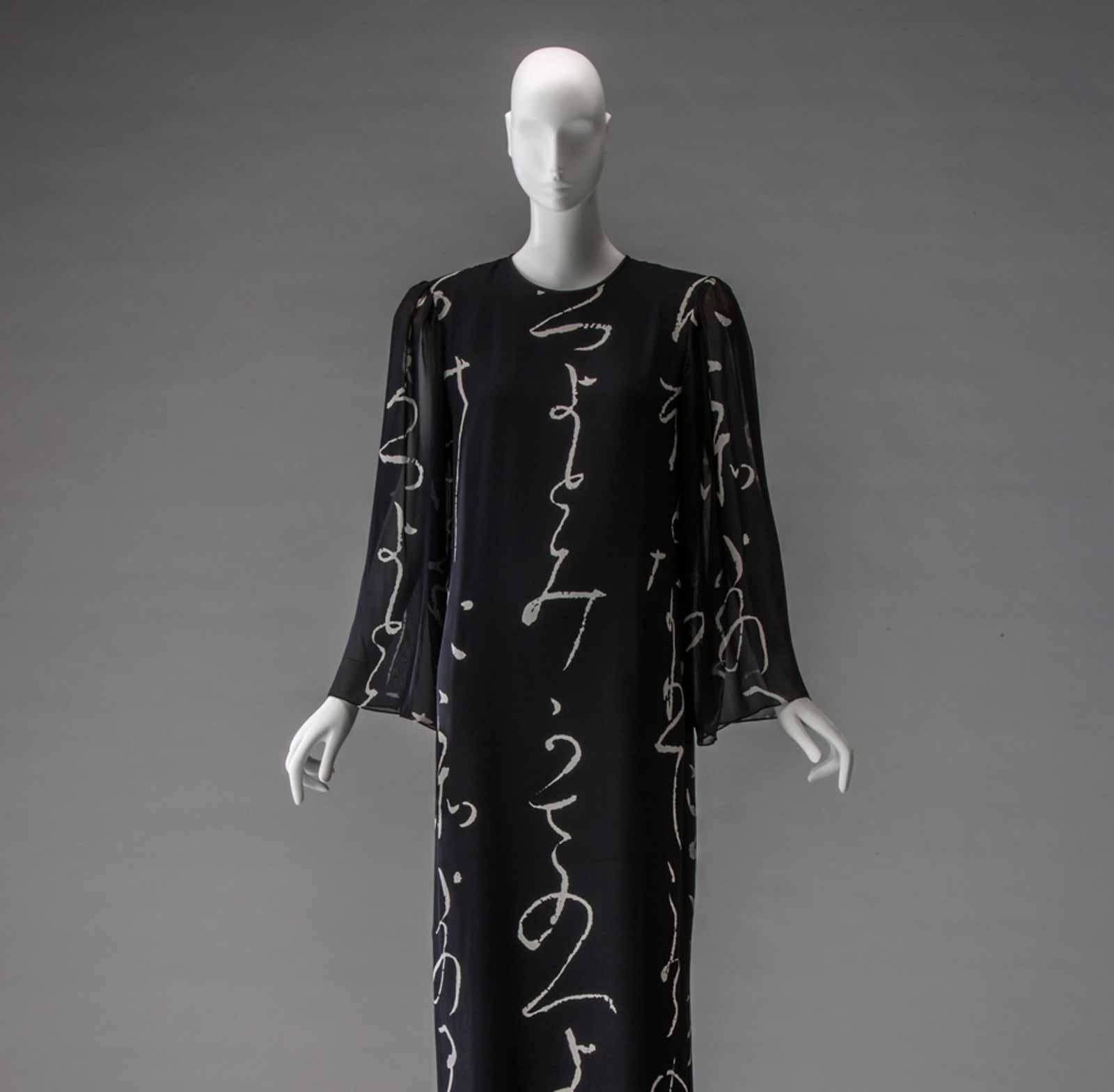

The relationship of the kimono with the human body is one of the most interesting aspects of this garment. While Western clothing embraces and enhances the body features of a person, the kimono deletes the body and becomes the focus of attention through its colors, motifs, and symbolism. Just like the Indian sari, the structure of the kimono is flat. From a single piece of fabric, the tan, of approximately 12 meters by 37 centimeters, the kimono is cut and sewn together leaving no scraps or waste. Cut into four parts, two pieces are used for the sleeves, sode, while the other two become the migoro, the main body panels. The collar, eri, and the narrow front panels, okumi, complete the garment.

Curators Yuri Morishima and Karin G. Oen note that “the kimono’s construction is flat,” and this flatness is the fulcrum of Kimono Refashioned, which explores the influence that kimono had in the Western fashion industry and art scene from the nineteenth century until the early twentieth century, and in a second section examines the impact that kimono has had on contemporary fashion.

Between the nineteenth and early twentieth century, fashion designers approached the kimono as a sizeable piece of fabric that could be transformed into dresses, coats, and cloaks. The 1875 dress by Misses Turner Court Dresses was created using a kosode, a looser, short-sleeved robe, the precursor of the kimono. Another example is the furlined coat with a samurai helmet design, fans, and cherry blossoms created at the end of the nineteenth century. The peculiarity of the coat is, as Morishima explains, is “the vertical orientation of the samurai helmet design, something that is not found in traditional Japanese fashion,” where this design would only be oriented horizontally. Throughout the mid-twentieth century until the present day, the flatness of the kimono has maintained its role as a source for experimentation in extravagance, complexity, and elegance.