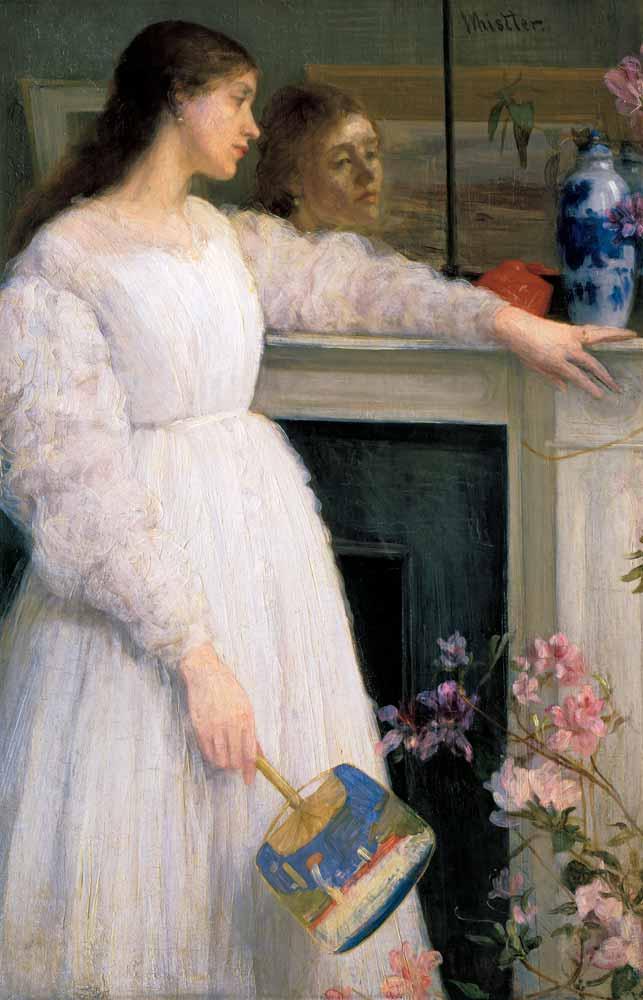

More than a model or muse, Hiffernan was a true partner to the ambitious young Whistler. Despite an extensive body of scholarship surrounding Whistler’s artistic achievements, little has been known about the degree of influence Hiffernan exercised, personally and aesthetically, during the years they lived together out of wedlock. Their unconventional lifestyle mirrors the defiant stance taken by Whistler in the paintings of Hiffernan, none more significant or controversial in its own time than Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl (1861-63, 1872). It is one from a suite of three paintings that forms the central unifying theme in the first exhibition to examine this complex relationship. The title, like many of Whistler’s paintings, alludes to music and suggests his primary interest is in the formal, abstract qualities of the work. Paintings as arrangements of color, line, and form.

Professor Margaret F. MacDonald from the University of Glasgow is the preeminent authority on Whistler’s art and life and served as the co-curator of this exhibition scheduled to open in February 2022 at the Royal Academy of Arts, London. She spoke to Art & Object about her discovery of Whistler, which evolved into a life-long passion. “I was getting a teaching diploma and I didn’t plan to study Whistler. It all started with the letters. Then when I went to the Frick and saw his paintings, the merging of colors, they were beautiful.” MacDonald turned again to “mining Whistler’s letters for information about his models.” She found those letters, “most revealing, particularly about the subtle power play between Whistler and Hiffernan. While he is raving about her beauty, he is searching for something in that face.” It was that searching, perhaps never absolved, that drove Whistler to produce this extensive body of work in painting, etchings, and drawing shown together here for the first time.