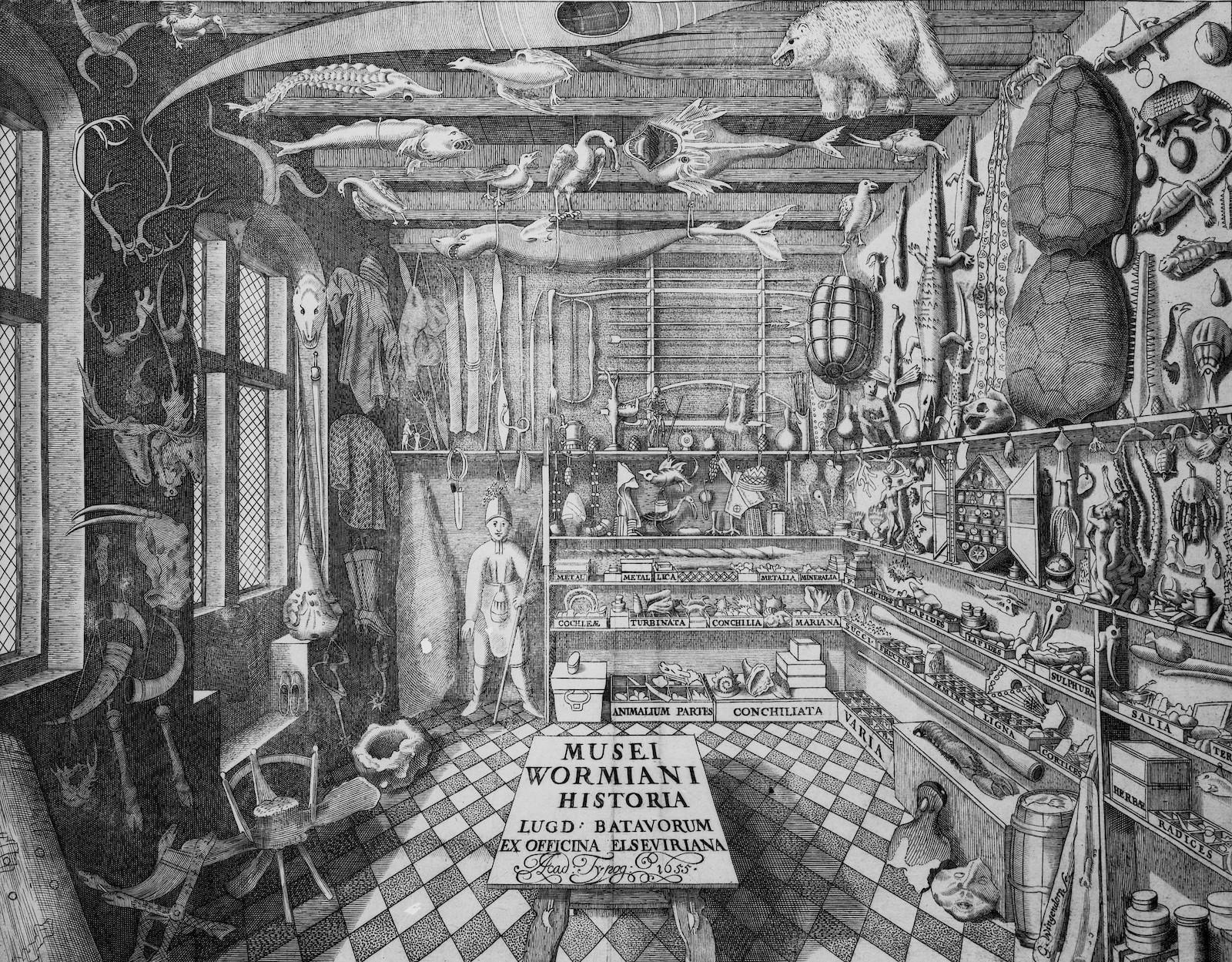

Whether stored in cabinets or large rooms, the display of such collections was often dictated by two primary categories: Naturalia and artificialia (or artefacta). The former consisted of objects from the natural world—from preserved animal and plant specimens to mineral and rock samples. The latter designated man-made objects—typically artworks and cultural artifacts. Many also collected scientifica—meaning scientific objects and tools.

Although such collections were kept by a wide range of groups and individuals—from Tsars to churches and apothecaries to scientific academies—a new wave of scholars have taken particular interest in the motives and cultural implications of the wealthy, often aristocratic, hobbyist collector.