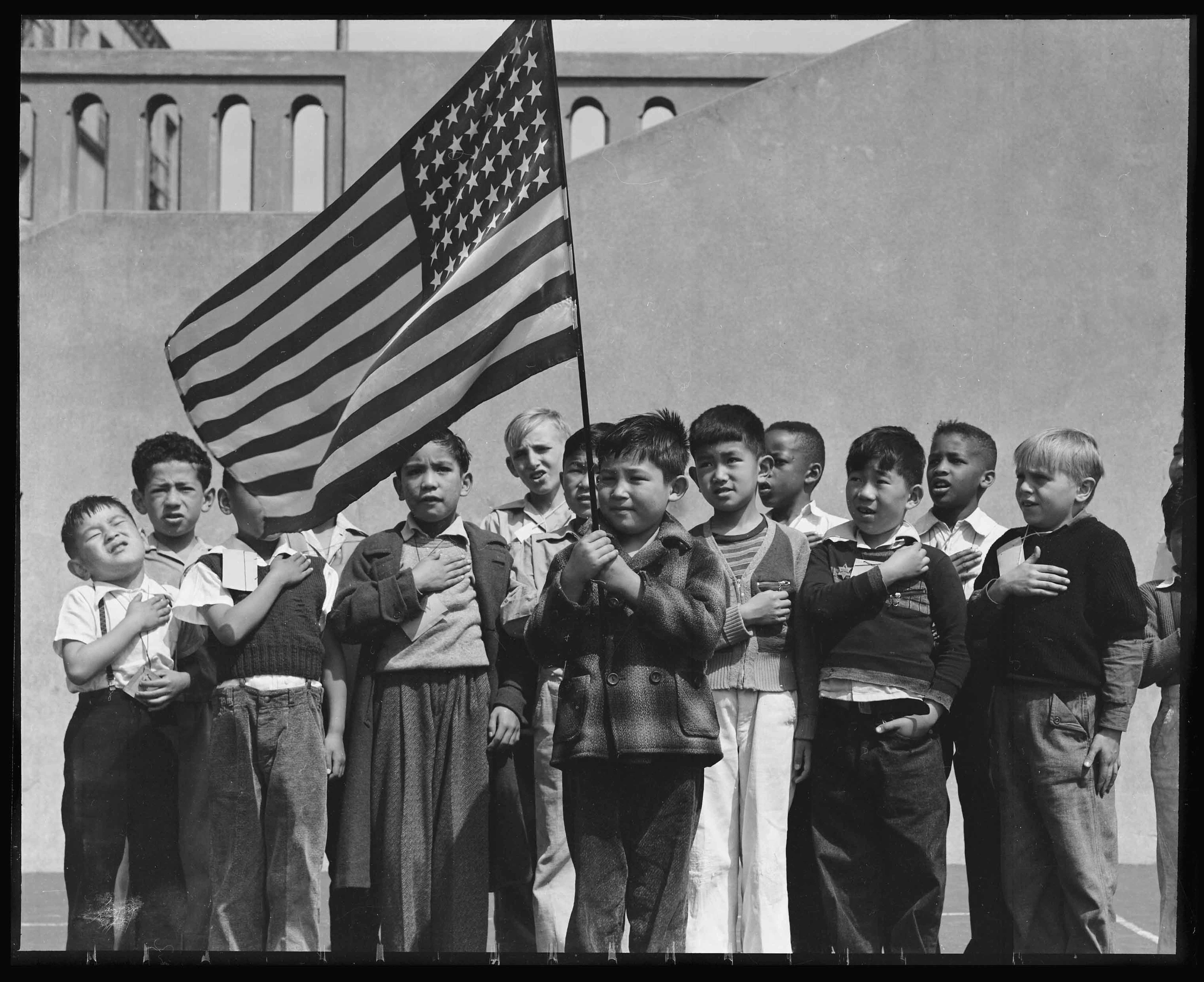

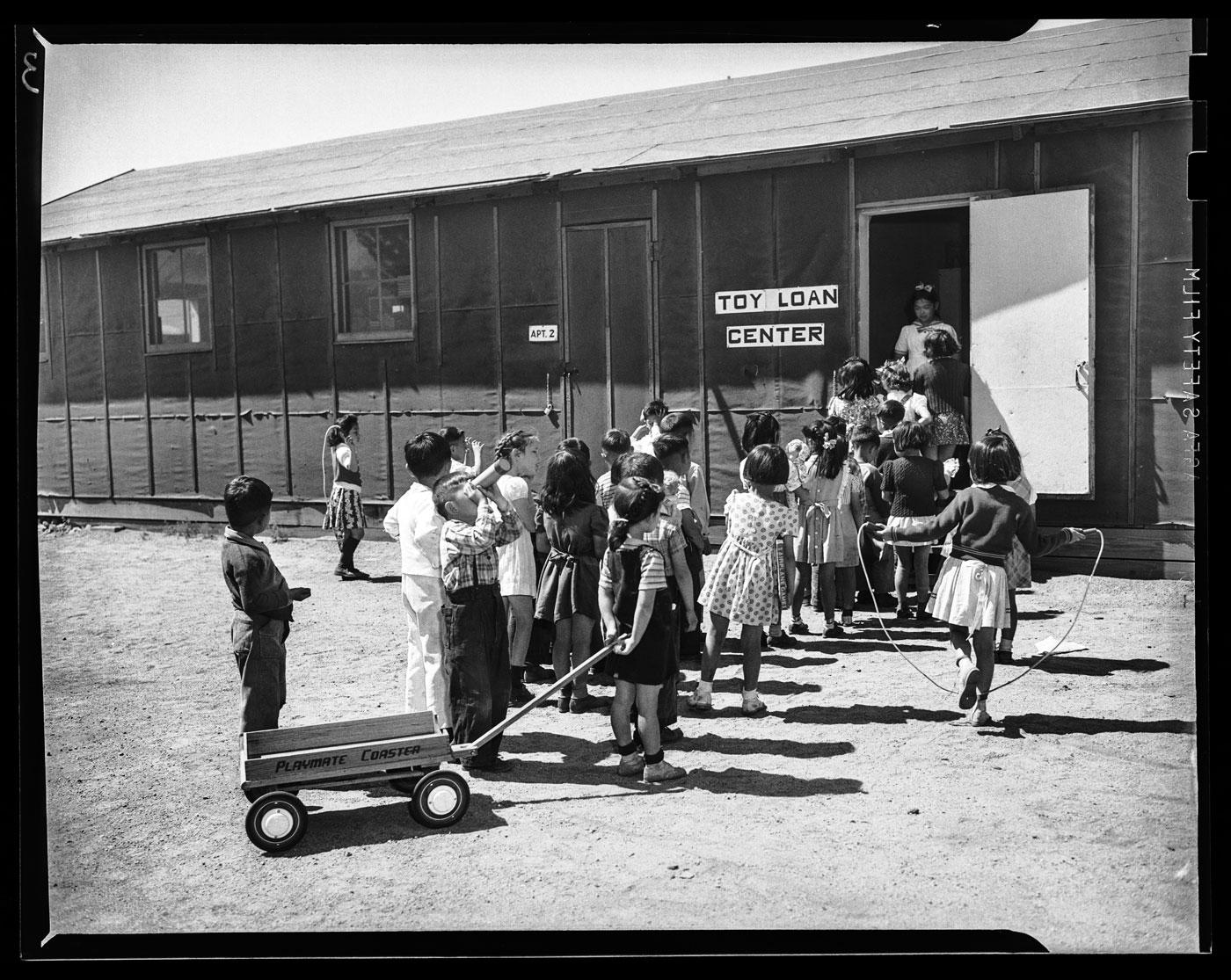

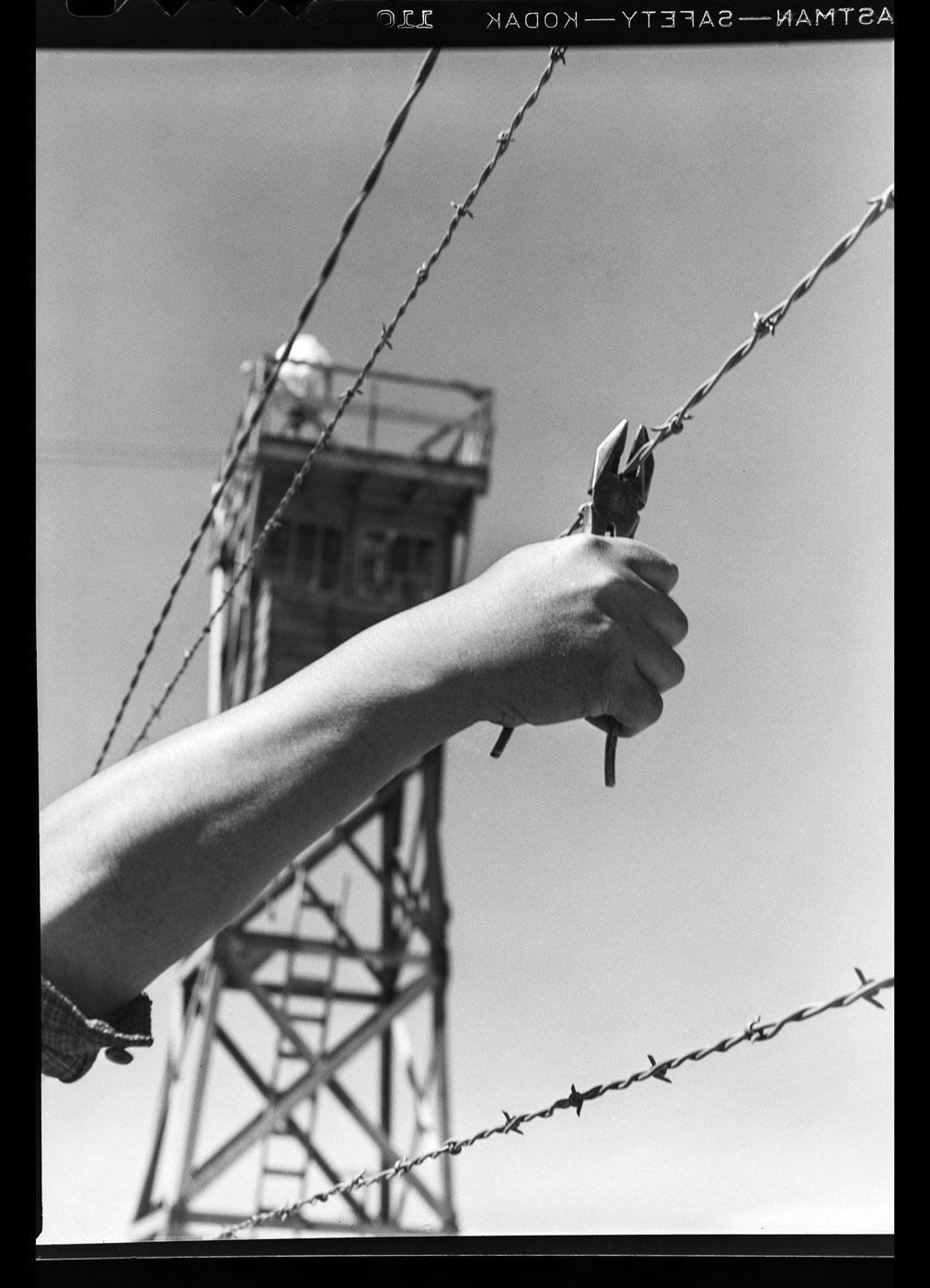

The exhibition opens with photographed portraits of Japanese American individuals before internment. Lange’s "San Francisco April 20 1942" shows a line of children, both of Japanese and European origin, reciting the pledge of allegiance. The photographer’s portraits of agricultural workers fill the subsequent gallery section, and we learn that these farmers’ success contributed to large-scale resentment and discrimination from nearby all-white communities. These groups of photographs establish Japanese-American narratives under the guise of growing wartime racial tension. But subsequent sections showing belligerent racist newspaper headlines spouting wartime hysteria along with repressive legislative documents are no less shocking than they would be had we encountered them without contextual lead-up. Toyo Miyatake’s photographs, such as 1944’s "Three Boys Behind Barbed Wire" follow and offer a more unmediated perspective: these images present barbed wire fences, watch towers and the brutally blunt everyday restrictions of life in the camps.

Dorothea Lange, "San Francisco, California, April 20, 1942"

“Then They Came for Me: Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II” at the International Center of Photography in New York City is a documentary exposé on a seldom-acknowledged history of American paranoia and racism: it examines the wartime internment of thousands of Japanese-Americans during the Second World War. The exhibition presents the stories of individuals who were physically, emotionally, and psychologically impacted by the midcentury policy of driving Japanese-Americans off their land and away from their livelihoods onto camps, which were often in remote and harsh parts of the country. However, the show goes beyond simply presenting historical episodes in photographic form: it brings a multitude of narratives to light, from individual families whose stories are told through portraits, quotes, and personal possessions, to more well known American photographers’ interventions, such as Dorothea Lange’s nuanced portrayals of the human impact that internment had on entire communities.

Toyo Miyatake, "Toy Loan Center," ca. 1944

Toyo Miyatake, "Hand and Barbed Wire," ca. 1944

The exhibition is far-reaching: it spans from the years leading up to American participation in the war and ends with documentation of ongoing reconciliation initiatives. ICP’s installation succeeds in demonstrating that Japanese wartime internment was not an event isolated in the past, to be relegated to a closed off section of history. Instead, the show thoroughly and successfully demonstrates the ongoing effects of forced displacement and the deeply troubling sentiment that preceded and followed legislative policy. By bringing a multitude of perspectives, voices, and media beyond photographs to the gallery walls, the show is immersive, important, and a crucial reminder of the ongoing and often-pervasive legacy of hasty racist political policy.

“Then They Came for Me: Incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II” runs through May 6th, 2018 at the International Center of Photography in New York City.