While executing a finger-tip search beneath the attic’s floorboards, Champion found something most homeowners would dread: a rat’s nest. But in a home over 500 years old, the debris that pests have gathered through their scavenging can be quite revealing.

Curator Anna Forest examines a fifteenth-century illuminated manuscript.

Lockdown has been a more productive period for some than for others. For archeologists working at Oxburgh Hall, a fifteenth-century manor in Norfolk, England, it has given them the opportunity to delve a little deeper into their work. Though the estate has been closed to visitors in recent months, an extensive restoration and repair project has continued.

Working alone, archeologist Matt Champion has worked examining the nooks and crannies of the manor’s attics. An $8 million restoration of the building’s roof began in 2016, giving researchers an opportunity to seek out previously neglected areas.

Oxburgh Hall undergoing roofing repairs.

Archaeologist Matt Champion looks under the floorboards at Oxburgh Hall.

This jumble of scraps included over 200 fragments of Elizabethan textiles, sections of early music, and pieces from early printed pages and handwritten documents. Also tucked in the walls were more modern items, like an empty box of chocolates and cigarette packs from the World War II era.

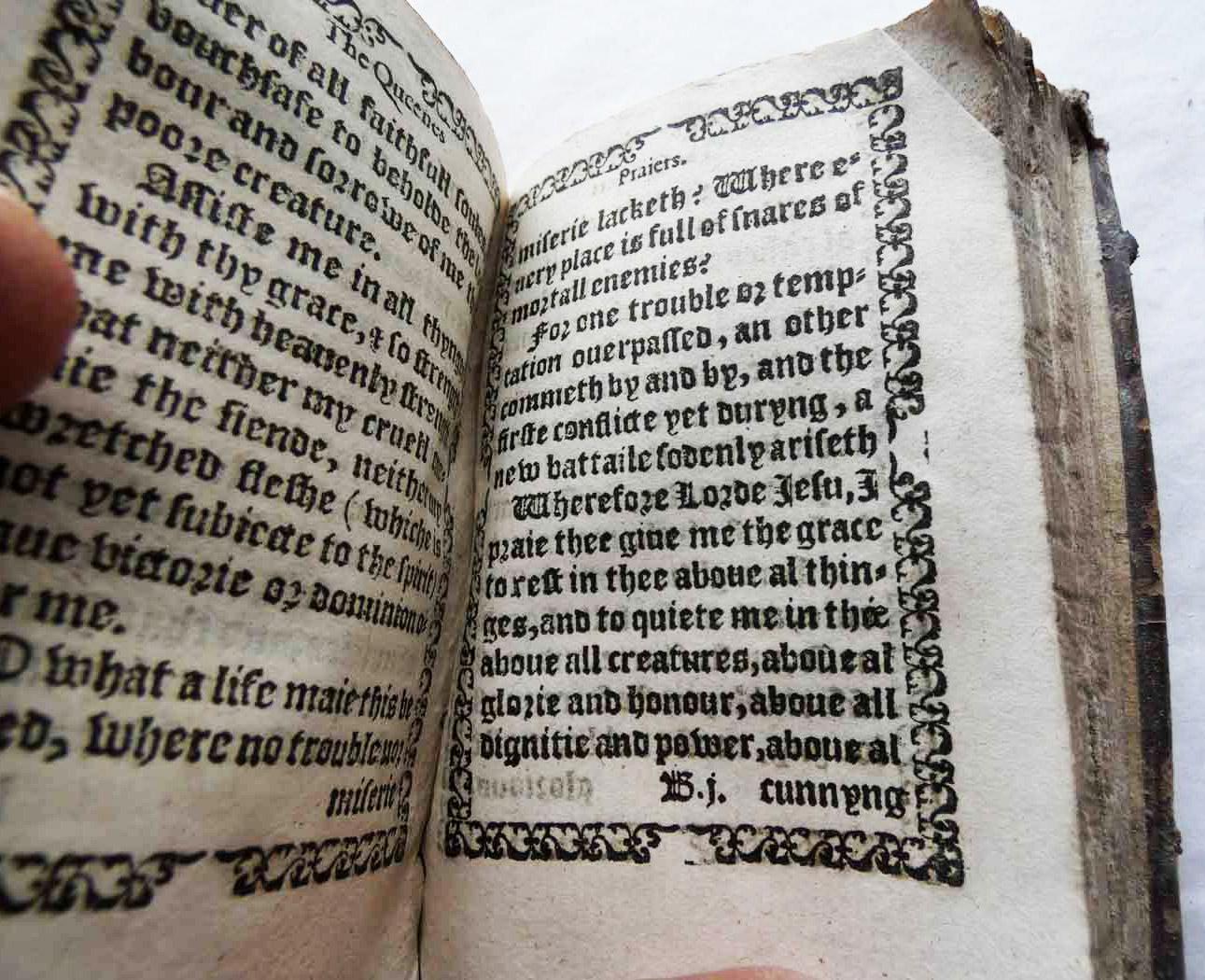

But construction workers found perhaps the most valuable items: a copy of the King's Psalms from 1568, and an intact page from a rare fifteenth-century illuminated manuscript. Little is known about the edition of the King's Psalms, as there is only one other known copy. The piece of parchment was discovered nearly intact in the building’s eaves, it’s gold leaf and blue illumination still vibrant.

The 1568 edition of The Kynges Psalmes written by Saint John Fisher.

According to Anna Forest, the National Trust curator who is overseeing the work, “The use of blue and gold for the minor initials, rather than the more standard blue and red, shows this would have been quite an expensive book to produce. It is tantalizing to think that this could be a remnant of a splendid manuscript and we can’t help but wonder if it belonged to Sir Edmund Bedingfeld, the builder of Oxburgh Hall.”

Between the fragments of documents and textiles, Oxburgh Halls’ researchers and curators have a whole new set of clues for learning about the medieval manor and its centuries of inhabitants. The rest of the debris discovered has been removed and archeologists will meticulously catalogue it, using it to piece together a greater picture of the lives lived in the home.