In 1969, when few African-American artists were able to exhibit their work, Wimberley was included in a group exhibition at CW Post College, in Brookville, New York. This constituted the first time he displayed his work publicly. However, in the next decade, he took advantage of many opportunities to display his art, participating in shows at The Hudson River Museum, Yonkers, New York (1971) and the Penthouse Gallery, Museum of Modern Art, New York (1972). His first solo exhibitions were in 1973, at The Black History Museum, Hempstead, New York, which opened in 1970 (now the African-American Museum of Nassau County), and at Acts of Art Gallery, in downtown New York. Owned by artists Nigel L. Jackson and Pat Grey, the gallery was an important part of the Black Arts Movement in the 1970s. In 1974, Wimberley had solo shows at Union Theological Seminary, New York City, and again at Acts of Art, where he displayed collages, drawings, and paintings. In February 1979, he participated in a show at Guild Hall Museum of the Eastville Artists, an informal council of African-American artists on Long Island’s East End devoted to promoting the arts. Other members were Alvin Loving, Robert Freeman, Nanette Carter, and Gaye Ellington (Duke Ellington’s granddaughter). Reviewing the show, Helen Harrison noted that Wimberley had “embraced a cool, formal vocabulary in his assemblages of paper and found objects.” She observed that several of the works included “scraps of used canvases, suggesting the rejection of a previous mode of expression.” She felt that Wimberley was searching “but cautiously.” That summer, when Wimberley was included in an exhibition at Peter S. Loonam Gallery in Bridgehampton, Harrison felt that his collages were “busier but just as controlled in their composition.”

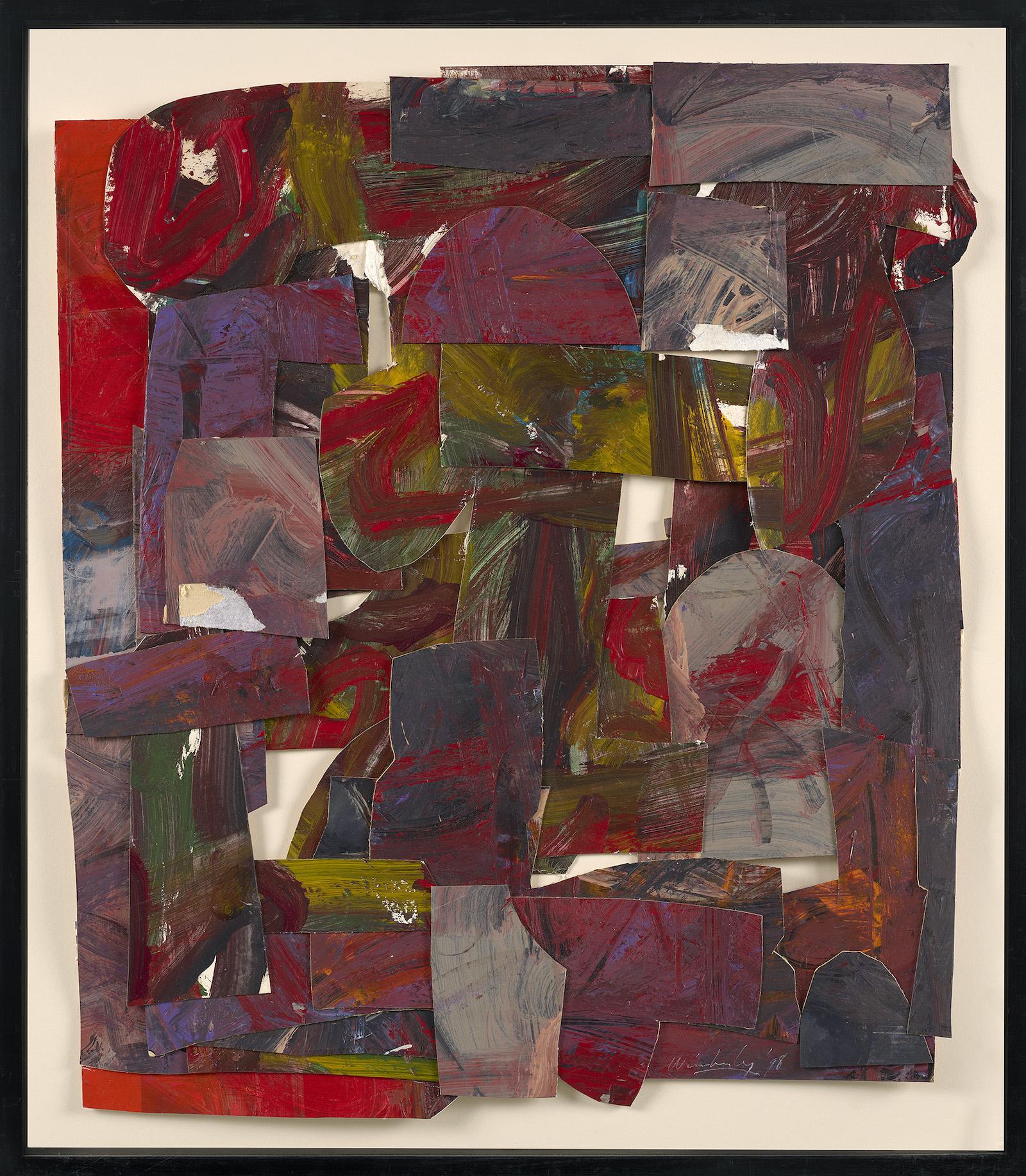

Texture played an especially important role in Wimberley’s art beginning in the 1970s. At the time, he was creating collages consisting of pieces of scrap cardboard, paper, cloth, and metal that he used to explore contours and spatial arrangements. In the next phase of his art, he incorporated three-dimensional found objects into his work. By the late 1980s, his emphasis was on paintings, created with a sculptural sensibility. He applied his pigments in a thick and pliant manner, using both scratching and raking methods to provide substance. Of his work on view in Abstract Energy Now, held at the Islip Art Museum in June 1986, Harrison wrote that “line and gesture” were “elegantly balanced” in his painting A Few Choice Things. This work was selected for illustration in Harrison’s review, which appeared in the New York Times. Harrison commented that the painting’s title pointed up “the fact that abstract art, even at its most spontaneous and intuitive is more choice than chance.” Reviewing Wimberley’s solo show at the Fine Arts Gallery, Long Island University, Southampton, the art historian Phyllis Braff stated that while like many abstract artists, Wimberley relied “on color, brushwork, and form, to invent a universe of visual sensations,” the strength “of his originality shows best in the way he builds emotional content with both color and a daring, experimental use of mass.” She observed the “sophisticated control that runs through these exuberant paintings.”

From the 1990s into the 2010s, Wimberley built on his previous art while setting out in new directions. His work of the early 1990s reveals his commanding use of a wide range of materials, including brushes made of steel wire, spatulas, and pumice. By the decade’s end, he often simplified his compositions, focusing on a particular inquiry that he pursued to a point of resolution.

At the turn of the new century, Wimberley was receiving widespread recognition. In 1997, he had solo shows at the Islip Art Museum, Long Island, and June Kelly Gallery, New York. In the catalogue for the latter, Rose Slivka, an important figure in American crafts, described

Wimberley as an artist who expressed jazz through swift brushwork and the spontaneous gesture but was also “very much a formalist and craftsman.” In 1998, he received the Pollock-Krasner Fellowship for the year. In 1999, a retrospective of his work was held at Adelphi University, and in 2000, his painting, Twilight Squall, was acquired by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York. When Wimberley had another show at June Kelly in 2001, Grace Glueck stated in her New York Times review that Wimberley’s paintings “are good to behold: beautifully brushed and infused with a light that magnifies their intensity.” Another retrospective of Wimberley’s art was held in 2004 at the Sage Colleges, in Albany, New York. In the show’s catalogue, Jim Richard Wilson described Wimberley’s recent work as “classical,” stating: “it is expression informed by reflection. It is apart from dominant contemporary trends. It is historically informed without being nostalgic. This work is sincere art in a time of disingenuous artifice.” At June Kelly Gallery in 2007, Wimberley exhibited some of his largest paintings. In the show’s catalogue, Phyllis Braff noted that throughout his career, the artist had “been coaxing expressive content from art’s key components” while observing that the works on view revealed “fresh, innovative probing . . . with many works taking on a special resonance.”

In 2010, Wimberley was the winner of the annual Guild Hall Artist Members’ Exhibition that was followed by a solo exhibition at the museum in 2012–2013. In the catalogue, Eric Ernst summarized the distinctiveness of the artist and his work, writing: “Frank Wimberley’s paintings have an excitement and energy that breaks the boundaries of the canvas. His art exudes depth and passion that invigorates the viewer. One cannot help but be drawn into the lushness of the paint and the way that it is masterfully handled by this amazing artist.”

Frank Wimberley is included in the following museum and corporate collections: Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois; Brooklyn Union Gas Company, New York; Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton, New York; Coca Cola Bottling Company, Philadelphia; David C. Driskell Art Center, University of Maryland, College Park; the Georgia Museum of Art, University of Georgia, Athens; Guild Hall Museum, East Hampton, New York; John and Vivian Hewitt Collection, Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts and Culture, Charlotte, North Carolina; James T. Lewis Gallery Morgan State, Baltimore Maryland; John Hoskins Estate, Atlanta University, Georgia; Islip Art Museum, New York; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York; PepsiCo, Purchase, New York; Pitney Bowes, Stamford, Connecticut; Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri; Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York; the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; Time Warner, New York; and Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut.

Christine Berry and Martha Campbell opened Berry Campbell Gallery in the heart of Chelsea on the ground floor in 2013. The gallery has a fine-tuned program representing artists of post-war American painting that have been overlooked or neglected, particularly women of Abstract Expressionism. Since its inception, the gallery has developed a strong emphasis in research to bring to light artists overlooked due to race, gender, or geography. This unique perspective has been increasingly recognized by curators, collectors, and the press. In March of this year, Roberta Smith reviewed Ida Kohlmeyer: Cloistered for the New York Times. This rare group of paintings from the artist’s estate had not been on view together since they were created in the late 1960s.

Berry and Campbell share a curatorial vision that continues with its contemporary program. Recently the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston acquired works by abstract painter, Jill Nathanson. Harry Cooper, senior curator and head of Modern art at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. chose a painting by Judith Godwin from the 1950s to hang in their Abstract Expressionist galleries. Works by Frank Wimberley were acquired by the Studio Museum in Harlem, New York, and the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, Washington, D.C.

Berry Campbell has been included and reviewed in publications such as the Wall Street Journal, Artforum, Art & Antiques, The Brooklyn Rail, the Huffington Post, Hyperallergic, East Hampton Star, Artcritical, and the New Criterion, the New York Times, and Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art.

Not only did the program expand, but in 2015, the gallery physically expanded, doubling its size to 2,000 sq feet. Furthering the ideals of the program, the gallery recently added the estates of Frederick J. Brown and Mary Dill Henry to its roster. Berry Campbell is located at 530 W 24th Street in the heart of Chelsea, New York, on the ground floor. The gallery is open to the public Tuesday through Saturday, 10:00 am to 6:00 pm or by appointment.