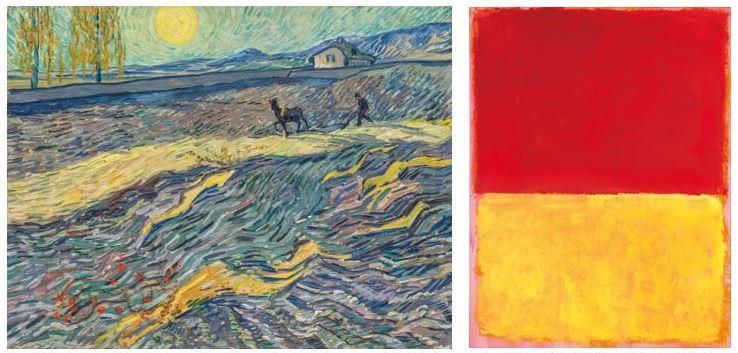

Left: Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), Laboureur dans un champ, oil on canvas, 1889. Estimate on Request. Right: Mark Rothko (1903-1970), Untitled, oil on paper mounted on canvas, 1969. Estimate: $10-15 million

New York – Christie’s is honored to have been entrusted with The Collection of Nancy Lee and Perry R. Bass, which will be offered throughout Christie’s 20th Century Week. The most substantial grouping will lead the specially retitled Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale Including The Collection of Nancy Lee and Perry R. Bass. Highlights will also be included in the Evening Sale of Post-War and Contemporary Art. Comprising 36 works in total, the collection is expected to realize in excess of $120 million.

Max Carter, Head of Department Impressionist and Modern Art, New York, remarked: “It is our signal honor to have been entrusted with The Collection of Nancy Lee and Perry R. Bass. Quietly assembled over forty years and comprising the best of Impressionist, Modern and Post-War art, the collection is led by five museum-quality masterworks—Kees van Dongen’s Fauve, larger-than-life Portrait de Madame Malpel, among the artist’s most celebrated and widely reproduced paintings; Henri Matisse’s marvel of Mediterranean light,Les régates de Nice; Joan Miró’s monumental Peinture, one of eighteen pivotal Collage Paintings, more than ten of which hang in major museums; Mark Rothko’s luminous, high-keyed Untitled, from 1969; and Vincent Van Gogh’s extraordinarily rich, gestural Laboureur dans un champ, the finest landscape by the artist to appear at auction in years.”

Aided and advised by Eugene V. Thaw, Klaus Perls and William Acquavella, the Basses were drawn to Impressionism, Fauvism, Surrealism and Abstract Expressionism—above all, to strong and expressive color. “A collection born with enthusiasm,” recalled Sid Bass, “became a lifetime of pleasure and joy.” In addition to her longstanding connection to the Kimbell Art Museum and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Mrs. Bass was also involved with the Collector’s Committee of the National Gallery of Art. In Washington, the Basses endowed an eponymous fund that has enabled works by Post-War and Contemporary artists to enter the National Gallery’s permanent collection. For Nancy Lee and Perry R. Bass, sharing art in the public sphere was an extension of their lifelong dedication to improving communities.

Leading the collection is Vincent Van Gogh’s Laboureur dans un champ. On mornings between 9 May 1889 and 16 May 1890, Van Gogh rose from bed and gazed through his window; the world outside appeared to him much like it does in this painting. Each morning the spectacle of the ascending sun would exhilarate and inspire him. The artist began this painting of a ploughman tilling the plot of land through his window in late August 1889 and completed it on 2 September. This was a significant development for Van Gogh, who had not handled his brushes since being removed from his studio by the doctors at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole following a devastating psychological episode.

An attack of this magnitude had last occurred in Arles on 23 December 1888, following a violent argument with Paul Gauguin in the small “Yellow House” they had shared for the previous two months. The argument led him to sever the larger part of his upper left ear.

The artist referred to Laboureur dans un champ in his letter to his brother Theo dated on or around 2 September: “Yesterday I started working again a little—a thing I see from my window—a field of yellow stubble which is being ploughed, the opposition of the purplish ploughed earth with the strips of yellow stubble, background of hills. Work distracts me infinitely better than anything else, and if I could once again really throw myself into it with all my energy that might possibly be the best remedy.” The image of the horse and ploughman is repeated in only one other Saint-Rémy painting, a related version but with variant motifs, which Vincent painted later in September.

Also highlighting the collection is Joan Miró’s Peinture (from collage), 4 April 1933. The present work comes from the series of eighteen large paintings completed in 1933, marking Miró’s commitment to resume oil painting on canvas following the period 1928-1931, when the artist had chosen to explore alternative means of expression including collage and assemblages. The present Peinture and its companion canvases are the direct outcome of this contest between painting and anti-painting, in which Miró revealed some of the most tantalizingly enigmatic, yet succinct plastic forms he had yet conceived.

Between 26 January and 11 February 1933, Miró fabricated the eighteen preliminary collages as the studies for the final canvases, at the rate of about one per day. Apart from dating each sheet on the reverse, Miró added nothing to the collages in his own hand. Realizing there would be insufficient room to store the completed canvases, Miró decided to paint the large works one at a time, pausing to unstretch and roll the completed canvas, and then reuse the stretchers for the next Peinture. Each picture would take several days, a week, or sometimes even fortnight to complete. Within each of these pictures, mysterious biomorphic shapes drift weightlessly within a seemingly boundless, yet cavernous inner space. These finished paintings are among the largest Miró had done to date; only a few earlier works surpass them in height or width.

Les régates de Nice, 1921, by Henri Matisse was painted only a few years into the artist’s life-long love affair with the city of Nice on the Cȏte d’Azur, this work was likely completed during the early spring of 1921. Les régates de Nice, portrays two young women at ease, in an airy, luminous interior, with a large French window opening to blue skies and the sea in the distance—classic hallmarks of Matisse’s art during the early 1920s. The standing figure is Henriette Darricarrère, the best known of Matisse’s models, and the second seated figure on the balcony is in fact Marguerite Matisse, the artist’s 26-year-old daughter, who had been staying with her father in Nice since late 1920.

In contrast to the often-gray atmosphere of the north, the artist delighted in the Mediterranean light during the winter. He moreover recognized that in this light, the way in which he organized his new pictures required a new synthesis of conception. The window, as the conveyor of light, became the crucial motif in the exploratory process Matisse commenced in early 1918. Matisse viewed the interior in Lesrégates de Nice as if from a ladder-like height, resulting in a perspective that flattens the deep space, which extends from the interior foreground to the far marine horizon. Throughout this vast distance, Matisse employs cinematic deep focus: every pictorial element, regardless of placement, is accorded the same degree of clarity.

Elegant and dramatically lit, evoking an haut bourgeois aura of opulent refinement, Kees van Dongen’s 1908 Portrait de Madame Malpel presaged a new line in the artist’s work, one which would increasingly define his career in coming decades—formal portraiture. Until this time his models were nearly all paid demi-mondaines—Van Dongen painted singers and dancers who performed in the cabarets and dance halls of Montmartre. Mme Malpel, however, was of far more elevated social standing; she was the wife of Charles Malpel, a lawyer from Montauban who became an art dealer and impresario in Toulouse, seeking to develop the city into an arts center for southwestern France.

Van Dongen presented Mme Malpel à l’espagnole, attired in a lace shawl and colorfully embroidered dress, her décolletage bordered with strands of sequins. In availing himself of espagnolisme in this portrait, Van Dongen was tapping into a potent and evocative theme with a distinguished pedigree in French painting. For the past century, artists of the School of Paris had been strongly attracted to the flesh-and-blood realism, the deeply sonorous color tonalities, and the sharp contrasts of light and shade that were the hallmarks of Spanish painting during its Siglo de Oro, and resonated as well in the much-admired art of Francisco Goya. Van Dongen's Madame Malpel thrusts upward against a fiery, volcanic background—the effect is stunning, Fauve, and superbly sophisticated.

Highlighting the selection of Post-War and Contemporary Art, which will be sold on November 15, is Mark Rothko’s masterful painting of 1969, Untitled. Painted in 1969, the work belongs to a celebrated series of paintings that Rothko created in the last year of his life. Having suffered an aortic aneurism in 1968, Rothko was advised by his physicians to limit himself to small-scale works on paper no larger than 40 inches. Rather than diminish the artist’s creativity, the series had the opposite effect. By late 1969 Rothko was painting on large-scale sheets of paper in a wide variety of media, producing some of his most significant work. Untitled envelops the viewer in its expansive field of luxurious color, gesturally applied in wide swathes of the brush that actively display the physical workings of the artist’s hand. In one of his most profound color pairings, Rothko creates a lavish, unmodulated field of highly saturated red alongside its counterpart, a luminous field of golden yellow.

Read more about the Bass Collection here.