The exhibition gathers together eight such subjects, primarily from the Norton Simon collections, to show how artists consistently foregrounded the inventive aspects of the odalisque. The diverse aesthetic approaches on view, ranging in date from the mid-19th through mid-20th centuries, indicate that painters perceived the orientalist subject to be highly adaptable, as it offered opportunities to embellish and innovate while embodying the ingenuity and resourcefulness of the artist’s own creative process. Harem environments—usually inaccessible to foreigners—were constructed in the artist’s studio using models dressed in exotic attire and an assortment of decorative props. And artists did not disguise the fact that their scenes were staged, whether by drawing attention to the studio setting or appropriating imagery from famous precedents. Revealing the picture’s fiction did not detract from its visual appeal, and only underscored that these chromatically bold and daring compositions were products of artistic imagination.

The earliest work in the exhibition is Achille Devéria’s Odalisque from c. 1830-35. Devéria seems not to have been concerned with the representational accuracy of his scene, given that he depicted an evidently European model with a cigarette rather than a hookah in her hand. Instead, the French artist focused on the striking formal parallels between the scarlet sphere of the odalisque’s drawstring pants and the oval-shaped panel on which she is painted. Thirty years later, realists like Frédéric Bazille rejected the artifice of Devéria’s stage-like setting by interpreting the odalisque in terms of modern life. Bazille’s Woman in a Moorish Costume (1869) strips away the pretense of an oriental interior by depicting a model as she prepares to be painted, securing the sash of her rented robe in the spare surroundings of the artist’s studio.

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973), Women of Algiers, Version “I”, January 25, 1955. Oil on canvas. 38-1/8 x 51-1/8 in. Norton Simon Art Foundation.

Pasadena, CA—The Norton Simon Museum presents Matisse/Odalisque, a vibrant exhibition that explores the theme of the odalisque, a reclining nude or concubine that was a popular subject in European art throughout the colonial period. These erotic images of women in the geographically vague “Orient” evoked a life of luxury and indolence far removed from 19th-century industrial society (and 21st-century standards of representing race and gender). Featuring pictures by Henri Matisse, Frédéric Bazille and Pablo Picasso, among others, this small exhibition demonstrates how artists approached the odalisque as an opportunity for creative fantasy by accentuating color, costume and dazzling surface effects.

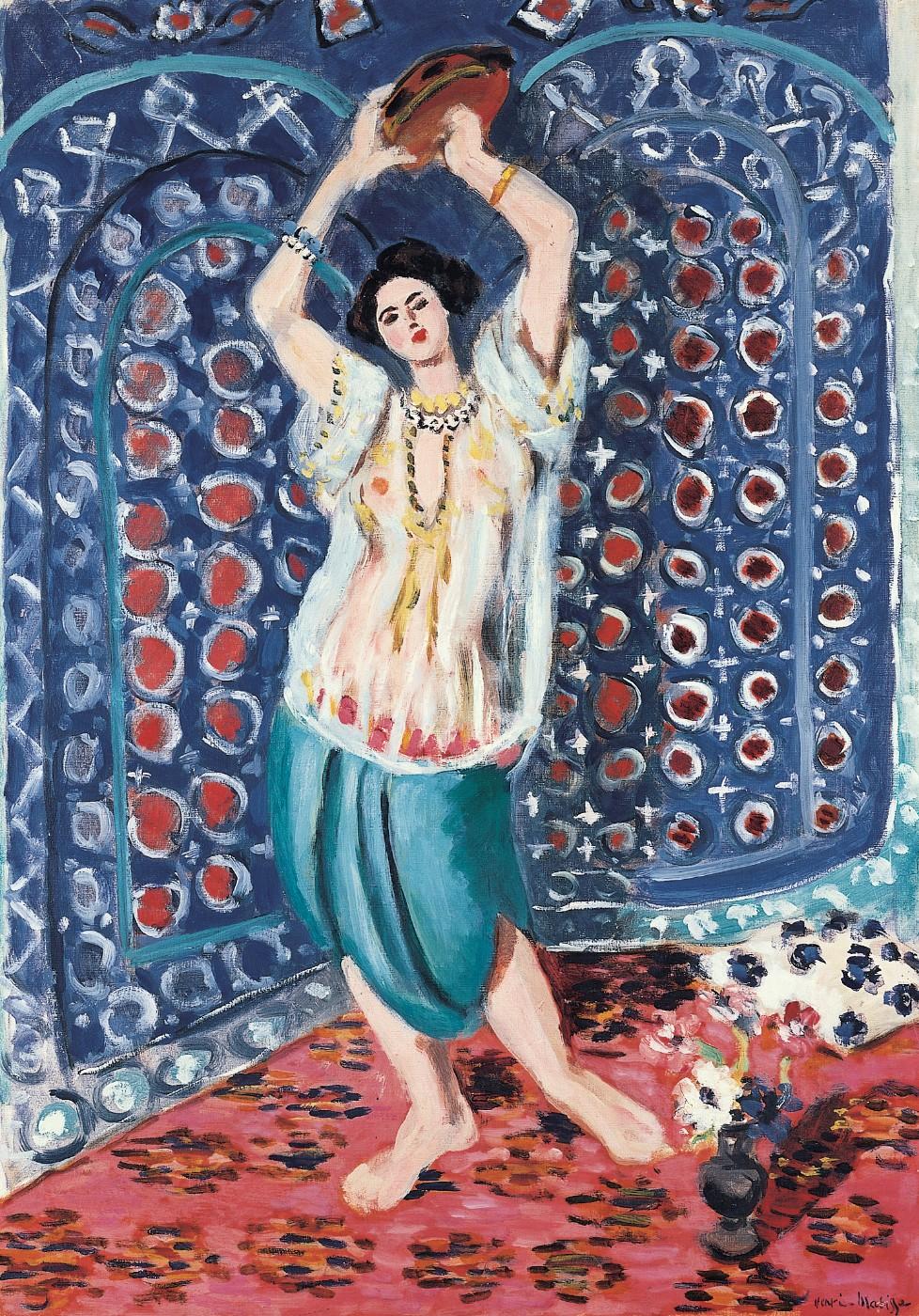

Henri Matisse (French, 1869-1954), Odalisque with Tambourine (Harmony in Blue), 1926. Oil on canvas. 36-1/4 x 25-5/8 in. Norton Simon Art Foundation.

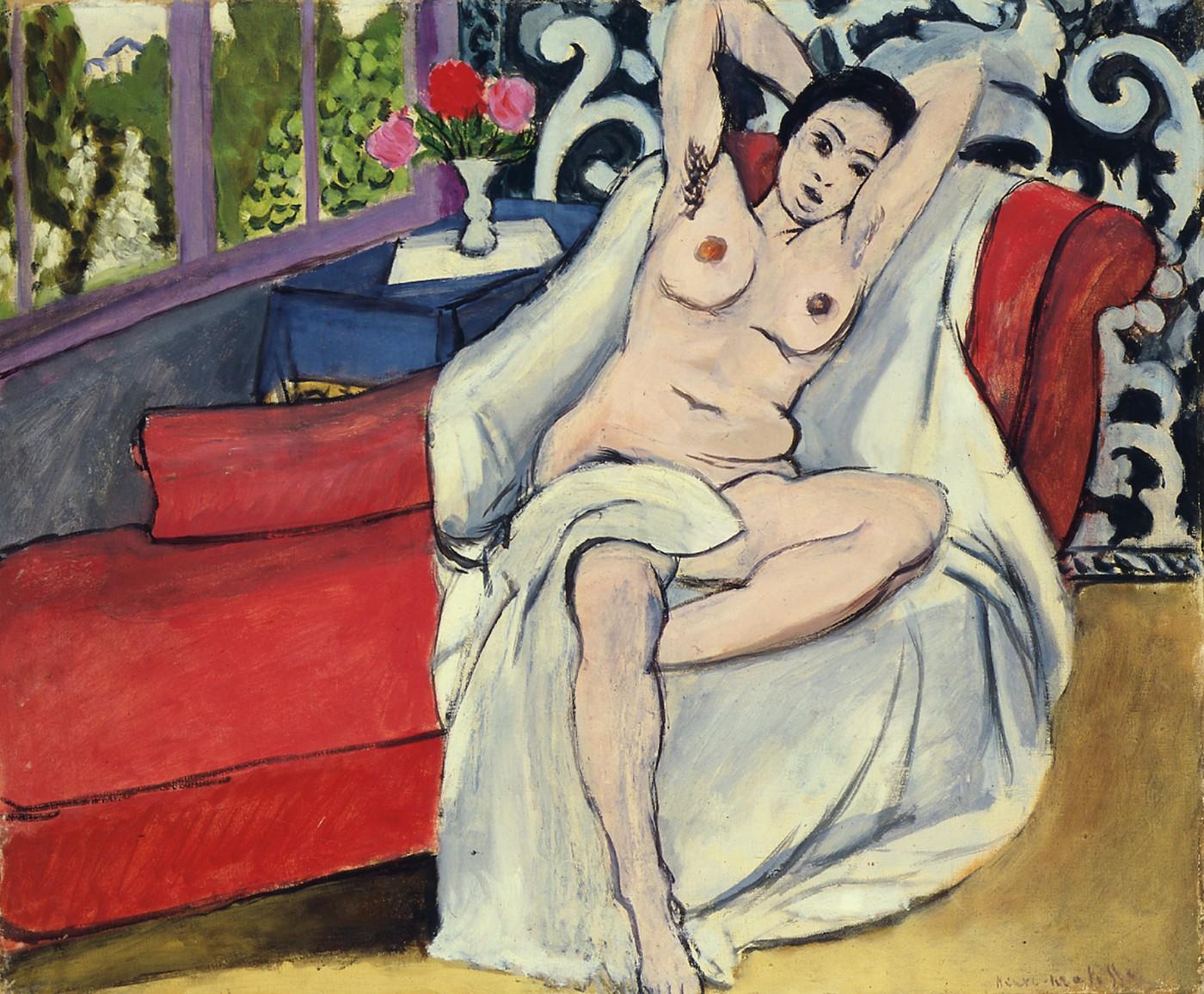

Henri Matisse (French, 1869-1954), Nude on a Sofa, 1923. Oil on canvas. 20 x 24 in. Norton Simon Art Foundation.

In the 20th century, the theme was revived once again by Henri Matisse. Matisse claimed that he made such pictures as an excuse to “paint the nude,” and because he had seen harems firsthand on his trips to Morocco. Yet the numerous odalisques that he produced in Nice in the 1920s revel in the imaginary, with excessively decorative environments that threaten to subsume the female figure altogether. Paintings like Odalisque with Tambourine (Harmony in Blue) (1926) flaunt the points of correspondence between the model’s elevated arms and the crisscross patterns of the North African textile that surrounds her. Related works by the artist in the exhibition include The Black Shawl (1917), Nude on a Sofa (1923) and an untitled drawing from 1936, donated to the Museum in 2018 by Carol Moss Spivak. This quest to unsettle the traditional hierarchy between figure and ground was one that Matisse pursued throughout his career, but in the odalisque he found a particularly complex and compelling format to further these ambitions.

Jean-Frédéric Bazille (French, 1841-1870), Woman in a Moorish Costume, 1869. Oil on canvas. 39-1/4 x 23-1/4 in. Norton Simon Art Foundation.

The exhibition concludes with Pablo Picasso’s remarkable recreation of the Women of Algiers (1834), an iconic harem scene by Eugène Delacroix. Picasso’s abstracted interpretation of the composition is one of 15 paintings and hundreds of works on paper of this subject that he produced in a concentrated burst of activity in late 1954 and early 1955. Although the Spanish artist had long admired Delacroix’s masterpiece, the impetus to paint an odalisque was likely inspired by the death of Matisse that November. Speaking of his longtime friend and artistic rival, Picasso explained, “When Matisse died, he left his odalisques to me.” The canvas in the Simon’s collection, Women of Algiers, Version I (1955), freely absorbs and reconfigures its sources, simplifying and flattening the forms into forceful fields of red, blue and black that allude to odalisques past while dramatizing the vision of the painter in the present.

Matisse/Odalisque is organized by Assistant Curator Emily Talbot. It is on view in the Museum’s small rotating gallery on the main level from Feb. 22 through June 17, 2019.

About the Norton Simon Museum

The Norton Simon Museum is known around the world as one of the most remarkable private art collections ever assembled. Over a 30-year period, industrialist Norton Simon (1907–1993) amassed an astonishing collection of European art from the Renaissance to the 20th century, and a stellar collection of South and Southeast Asian art spanning 2,000 years. Modern and Contemporary Art from Europe and the United States, acquired by the former Pasadena Art Museum, also occupies an important place in the Museum’s collections. The Museum houses more than 12,000 objects, roughly 1,000 of which are on view in the galleries and gardens. Two temporary exhibition spaces feature rotating installations of artworks not on permanent display.