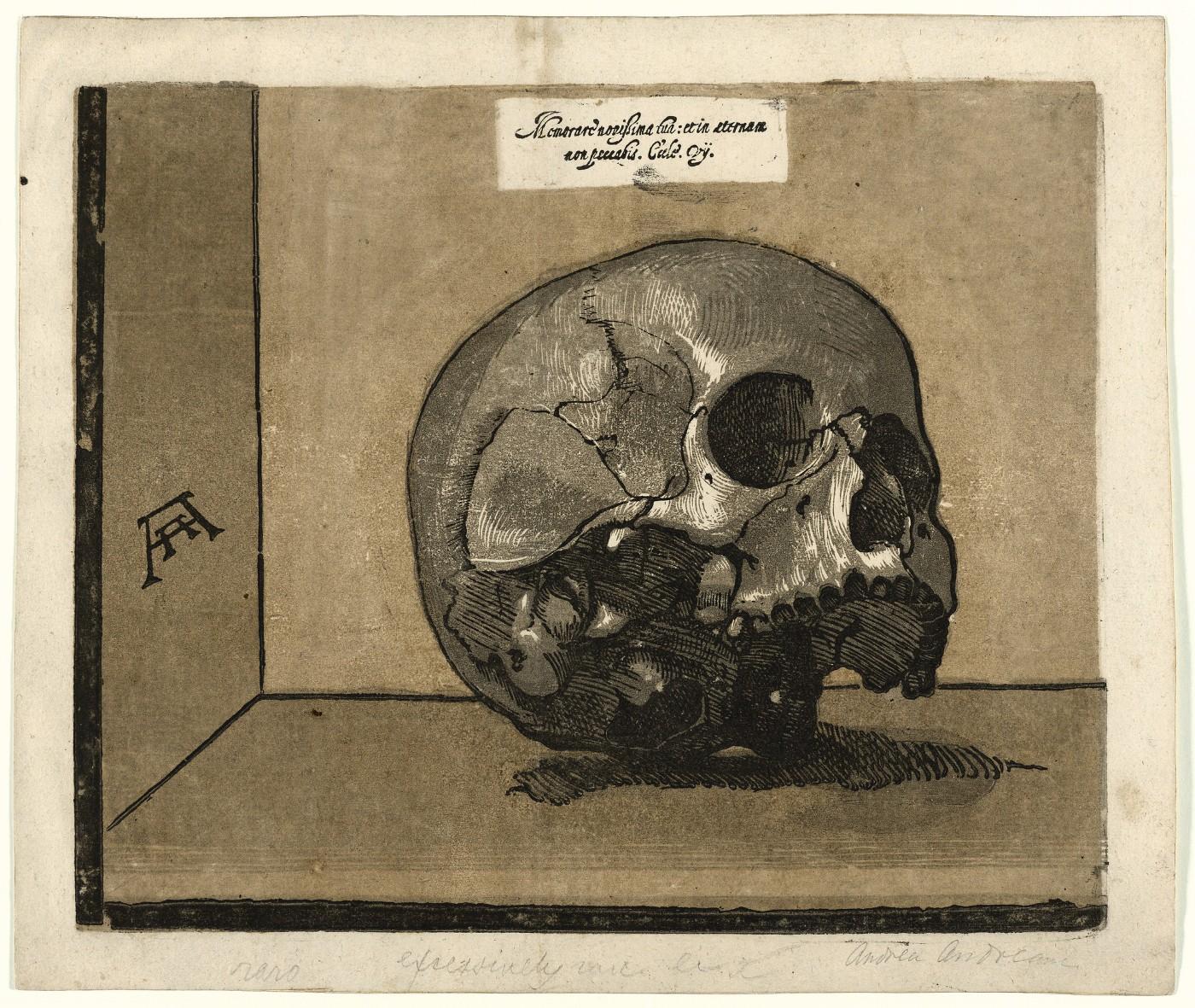

Andrea Andreani, after Giovanni Fortuna (?), "A Skull," c. 1588, chiaroscuro woodcut from 5 blocks in light brown, light gray, medium gray, dark gray, and black, The British Museum, London, 1861,0518.199, photo © 2018 The Trustees of the British Museum

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) presents The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy, the first major exhibition on the subject in the United States. Organized by LACMA in association with the National Gallery of Art, Washington, this groundbreaking show brings together some 100 rare and seldom-exhibited chiaroscuro woodcuts alongside related drawings, engravings, and sculpture, selected from 19 museum collections. With its accompanying scholarly catalogue, the exhibition explores the creative and technical history of this innovative, early color printmaking technique, offering the most comprehensive study on the remarkable art of the chiaroscuro woodcut.

“LACMA has demonstrated a continued commitment to promoting and honoring the art of the print,” said LACMA CEO and Wallis Annenberg Director Michael Govan. “Los Angeles is renowned as a city that fosters technically innovative printmaking and dynamic collaborations between artists, printmakers, and master printers. This exhibition celebrates this spirit of invention and collaboration that the Renaissance chiaroscuro woodcut embodies, and aims to cast new light on and bring new appreciation to the remarkable achievements of their makers.”

“Although highly prized by artists, collectors, and scholars since the Renaissance, the Italian chiaroscuro woodcut has remained one of the least understood techniques of early printmaking,” said Naoko Takahatake, curator of Prints and Drawings at LACMA and organizer of the exhibition. “With its accompanying catalogue, the exhibition documents a decade of research that advances scholarly understanding of a broad range of critical questions—from attribution and chronology, to artistic collaboration, materials and means of production, publishing histories, aesthetic intention, and Page 2 audience—forming a clearer view of the genesis and evolution of this captivating and complex medium.”

Following its presentation at LACMA, The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy travels to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., where it will be on view October 14, 2018–January 20, 2019.

Exhibition Overview

Displaying exquisite designs, technical virtuosity, and sumptuous color, chiaroscuro woodcuts are among the most visually arresting and beautiful prints of the Renaissance. First introduced in Italy around 1516, the chiaroscuro woodcut was the most successful early foray into color printing in Europe. Taking its name from the Italian terms for “light” (chiaro) and “dark” (scuro), the technique involves printing an image from two or more woodblocks inked in different hues, employing tonal contrasts to create three-dimensional effects. A distinctive characteristic of the technique was the ability to print the same image in a variety of palettes. Over the course of the century, the chiaroscuro woodcut engaged some of the most celebrated painters and draftsmen of the time, including Titian, Raphael, and Parmigianino, and underwent sophisticated technical advancements in the hands of talented printmakers active throughout the Italian peninsula. The medium evolved in subject, format, and scale, testifying to the vital fascination among artists and collectors in the range of aesthetic possibilities it offered. Embraced as a means of disseminating designs and appreciated as works of art in their own right, these novel prints exemplify the rich imagery and technical innovation of the Italian Renaissance.

Exhibition Organization

The Chiaroscuro Woodcut is organized chronologically, exploring the contributions of the major Italian workshops to chart the technique’s development through the 16th century. It begins with Ugo da Carpi, the Italian progenitor of the technique, and his work in Venice and Rome (c. 1516–27). It continues to the workshops of Parmigianino in Bologna (1527–30); Niccolò Vicentino (c. 1540s); Domenico Beccafumi in Siena (c. 1540s); the dissemination of the technique in smaller workshops throughout the Italian peninsula (c. 1530s–80s); and concludes with Andrea Andreani in Florence, Siena, and Mantua (c. 1580s–1610).

The first section is The Italian "Invention": Uga da Carpi in Venice and Rome c.1516-1527. In 1516, Ugo claimed he had discovered a “new method of printing in chiaro et scuro [light and dark],” and applied for a privilege from the Venetian Senate that would protect the process against copyists. Although Northern European artists had developed the technique a decade earlier, this hardly diminishes the significance of Ugo’s contribution to the medium, which was to become most widely practiced in Italy. Through his technical proficiency and distinguished associations with Titian in Venice and Raphael in Rome, Ugo created chiaroscuro woodcuts of remarkable aesthetic sophistication and forged a new market for these prints. Within a brief period, he advanced the technique from a basic two-block linear mode (Hercules and the Nemean Lion, after Raphael or Giulio Romano, c. 1517–18), to a more complex tonal approach using as many as four blocks (Aeneas and Anchises, after Raphael, 1518). Ugo occasionally collaborated directly with a designer. His Saint Jerome, c. 1516, transmits the vitality of Titian’s energetic draftsmanship, which may have been laid down by the artist onto the block or transferred from a drawing. But he also worked independently, availing himself of engravings as models for his chiaroscuros (Ugo da Carpi, after Marcantonio Raimondi, Hercules and Antaeus, c. 1517–18, and Marcantonio Raimondi, after Raphael, Hercules and Antaeus, engraving, c. 1517– 18). While Ugo did not conceive his own designs, he performed or closely supervised all other aspects of production. His pioneering works, characterized by an admirable refinement of cutting, ink preparation, and printing, set the foundation for the technique’s efflorescence in Italy through the Renaissance.

The next section is A Collaborative Art: Parmigianino, Uga da Carpi, Antonio da Trento in Bologna, c.1527-1530. The painter Francesco Mazzola, called Parmigianino, demonstrated a keen appreciation for prints as a means of disseminating inventions and expressing beautiful draftsmanship. While his printmaking ventures began in Rome around 1526, his investment in the practice deepened in Bologna, where he resettled in 1527 (following the sack of Rome) until his return to his native Parma in 1530. There, he produced his own etchings and began his engagement with chiaroscuro. The chiaroscuro woodcuts issued from Parmigianino’s Bolognese shop match the painter’s graceful draftsmanship with skilled cutting, fine inks, and exacting printing, revealing the intimacy of his collaboration with his two cutters, Ugo da Carpi and Antonio da Trento. Ugo’s masterwork Diogenes, after Parmigianino, (c. 1527–30), an unparalleled achievement in the history of the technique, dates to this period. It depicts the Greek philosopher Diogenes seated before the barrel he made his home with a plucked chicken to the right, which alludes to his mockery of Plato’s description of man as a species of featherless biped. Working closely with Parmigianino, Ugo orchestrated the designs of four interdependent and overlapping blocks to model the dynamic figure, capture the fluid movement of his drapery, and render the distinctive texture of the fowl’s exposed skin. In contrast to Ugo’s painterly approach, Antonio’s refined cutting of supple, calligraphic strokes, witnessed in Nude Man Seen from Behind (Narcissus), after Parmigianino, (c. 1527–30), sensitively transmits Parmigianino’s fluent drawing hand. Impressions printed in different palettes demonstrate how changes in color not only alter tonal relationships, but equally affect the mood and treatment of a subject.

A Commercial Enterprise: Niccolo Vincentino and his Workshop, c.1540s examines the chiaroscuros of the most prolific Renaissance workshop. While little biographic information is known about Vicentino, his name implies origins in the Veneto, and Giorgio Vasari (the 16th-century artists’ biographer) placed his activity after Parmigianino’s death in 1540. Although some uncertainty has surrounded the attribution of many of Vicentino’s unsigned prints, study of cutting techniques, printing characteristics, and publishing histories provides new grounds for establishing his workshop’s oeuvre. Most of his chiaroscuros were modeled on Italian designs from the mid-1510s to the late 1530s, primarily ones by Parmigianino (Circe Drinking [Circella], after Parmigianino, c. 1540s) and Raphael (attributed to Raphael, Miraculous Draught of Fishes, c. 1514, and Vicentino, Miraculous Draught of Fishes, after Raphael, c. 1540s). However, as Vicentino commonly worked from drawings independently of their creators, the chronology of his output remains unclear. Vicentino’s workshop introduced strikingly bold, saturated colors to the Italian chiaroscuro woodcut as evidenced in multiple impressions of Saturn, after Pordenone, c. 1540s, and its production prioritized expediency, pointing to the technique’s increased commercialization. The substantial survival of impressions in diverse palettes testifies at once to the success of Vicentino’s practice and to the broadening audience for Italian chiaroscuro woodcuts.

The following section examines the workshop of Painter-Printmaker: Domenico Beccafumi, c.1540s. The foremost artistic personality of his native Siena, Beccafumi was charged with many of the city’s most prestigious commissions for paintings, marble inlay designs, and sculpture. He turned to printmaking late in his life, producing nine pure chiaroscuro woodcuts and six engravings printed with tonal woodblocks. Among Italian chiaroscurists, he is unique for having designed and cut his own blocks, and his prints are immediate, spirited expressions of his remarkable vision. The artist probed the possibilities of the chiaroscuro process at each stage of production. He used unconventional tools for cutting, resorted occasionally to printing by hand, and exploited fully the technique’s inherent potential for variation, changing the manner he inked and printed his blocks. Among his most mature works are his closely related Apostle with a Book and Saint Philip (both c. 1540s), which are striking for their ambitious scale, bold palette, and palpably energetic cutting that assert the material of the wood. Like his paintings and drawings, his prints display his fertile invention, bold draftsmanship, and fluent expression of dramatic chiaroscuro.

The Dissemination of Technique: c.1530s-80s reveals how, alongside the major practitioners, other Italian painters and printmakers also explored the chiaroscuro woodcut to great creative ends. The designs of Titian, Raphael and his circle, and Parmigianino, which were vital to the development of the technique, continued to be important sources through the middle of the century. However, as enthusiasm for the novel technique spread to new artistic centers throughout the peninsula, different styles and manners were espoused. Notably, the painters Antonio Campi, Federico Barocci, and Marco Pino (Giovanni Gallo, after Marco Pino, Holy Family with the Infant Saint John the Baptist, 1570s–80s) introduced the technique to Cremona, Urbino, and Naples, cities that were not major print publishing centers. Moreover, the introduction of new subjects, including landscape and genre by printmakers such as Nicolò Boldrini, discloses a continued ambition to innovate. Boldrini’s magnificent Tree with Two Goats, late 1560s, is the only treatment of pure landscape in Italian chiaroscuro. Production in these smaller workshops, often by artists and printmakers who engaged only occasionally with the technique, was generally limited in numbers. Yet despite more episodic and attenuated production, the appreciation for chiaroscuro woodcuts was undoubtedly sustained through these decades. Crucially, as the century advanced, the great variety of prints that became available elicited critical standards in their appreciation among an ever more discerning audience.

In a career spanning three decades, printmaker Andrea Andreani produced some 35 chiaroscuro woodcuts. He primarily took up the designs of artists in the various centers of his activity—namely Florence, Siena, and his native Mantua—working with esteemed living artists and adopting the inventions of great masters of earlier generations. The section The Final Flourishing: Andrea Andreani, c.1580s-1610, explores the printmaker who displayed a remarkable talent for establishing artistic connections and cultivating the favor of an elite local patronage. Andreani always acted as his own publisher, and his output appears aimed principally at highend collectors and art connoisseurs. Andreani brought great ambition to the medium, quickly becoming its most accomplished practitioner of late century. Notably, he produced the first chiaroscuro woodcuts in Italy composed from two or more sheets from multiple sets of blocks. These prints achieve a grand pictorial scale that rivals the impact of painting, signaling an important shift in function and taste. Andreani also broadened the scope of subjects (for example, A Skull, after Giovanni Fortuna (?), c.1588, a compositionally sparse but technically complex chiaroscuro that is a vivid reminder of human mortality); moreover, he looked beyond traditional graphic sources for his models, including works of sculpture, bronze reliefs, and marble intarsia. Three different views of Giambologna’s famous Florentine marble sculpture, Rape of a Sabine, were both Andreani’s first chiaroscuro woodcuts as well as the earliest Italian ones to record a sculptural work (Rape of a Sabine, after Giambologna, 1584). After 1600, Andreani shifted his practice to republish the chiaroscuro woodcuts of an earlier generation of printmakers. These final years of his career were spent looking back at the chiaroscuro medium, which he himself had brought to new levels of technical and visual refinement.

A vital aspect of the scholarly research were collaborative studies by art historians, conservators, and conservation scientists that explored the materials and means of chiaroscuro production. The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy is the first exhibition on the subject to integrate such interdisciplinary, technical research. LACMA’s presentation features findings from the conservation and material science investigations, including examples of some of the commonly used ink colorants, recreations of the printing process, and an overview of an extensive conservation treatment endeavor.

Catalogue

The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy | $60 by Naoko Takahatake (Editor), with contributions by Jonathan Bober, Jamie Gabbarelli, Antony Griffiths, Peter Parshall, and Linda Stiber Morenus. Featuring more than 100 prints and related drawings, this book documents a decade of pioneering interdisciplinary research, combining studies from the fields of art history, conservation, and material science to present the first comprehensive assessment of the subject. Essays and entries by noted scholars trace the chiaroscuro woodcut’s creative origins, evolution, and reception, and provide authoritative interpretations of their materials and means of production. Brimming with full-color illustrations of rare, exquisite works, this groundbreaking study offers a fresh interpretation of these remarkable prints, which exemplify the beauty and innovation of Italian Renaissance art.

Public Programming

Talk: Art, Conversation, and Science: A Closer Look at Chiaroscuro Woodcuts

Saturday, June 30, 2018 | 2 pm Brown Auditorium | Free

In preparation for the exhibition The Chiaroscuro Woodcut in Renaissance Italy, LACMA’s conservation center undertook an extensive technical study, which shed new light on the materials and production methods of these pioneering color prints. Naoko Takahatake, Prints and Drawings Curator, Erin Jue, Associate Paper Conservator, and Charlotte Eng, former Andrew W. Mellon Senior Scientist and Head of Conservation Research, will discuss the conservation treatment of Antonio da Trento’s Martyrdom of Two Saints and present some findings from their interdisciplinary research.

Ciaramella Early Music Ensemble

June 3, 2018 l 6 pm Bing Theater | Free

Ciaramella Early Music Ensemble performs early Renaissance music in conjunction with the exhibition.