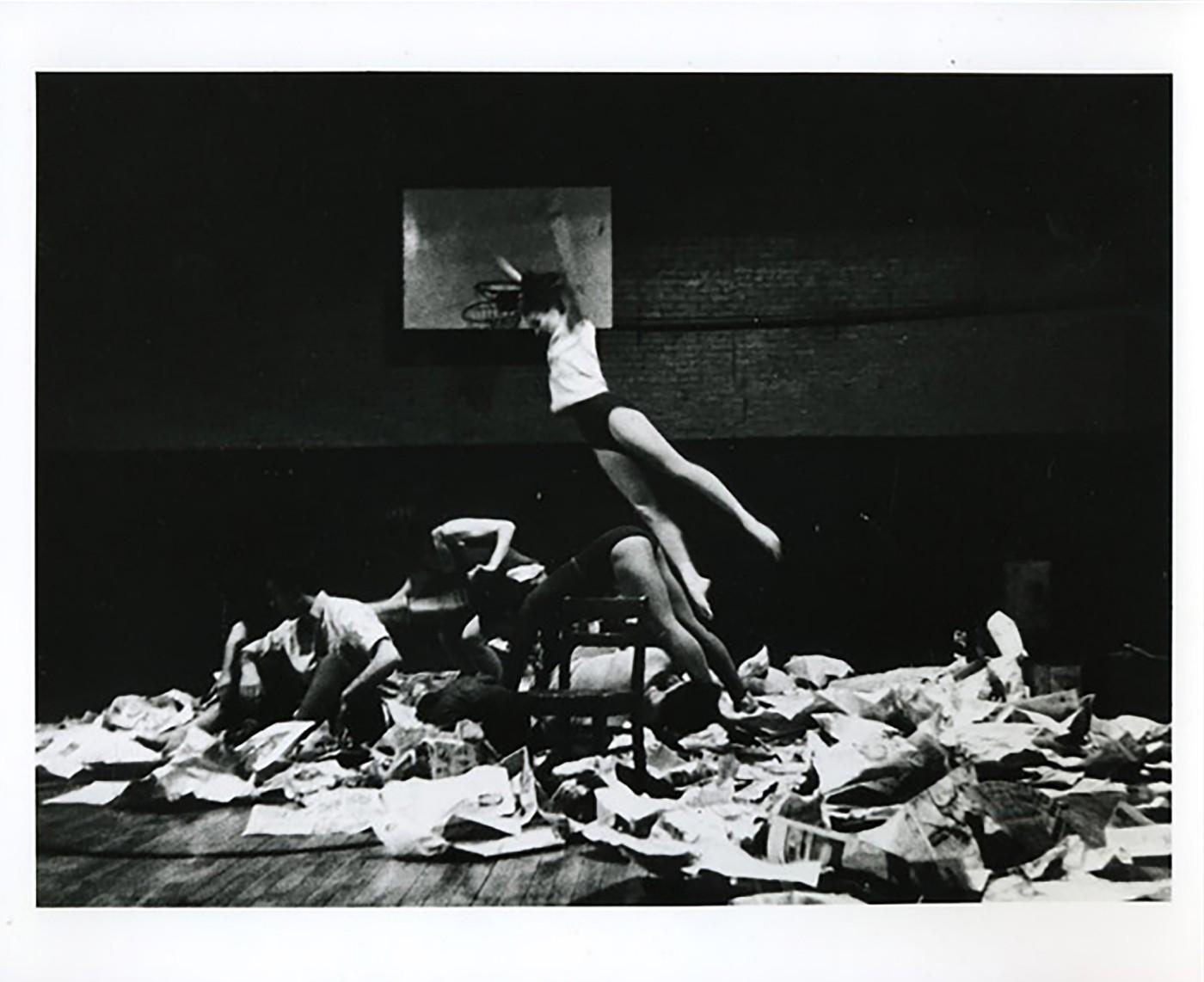

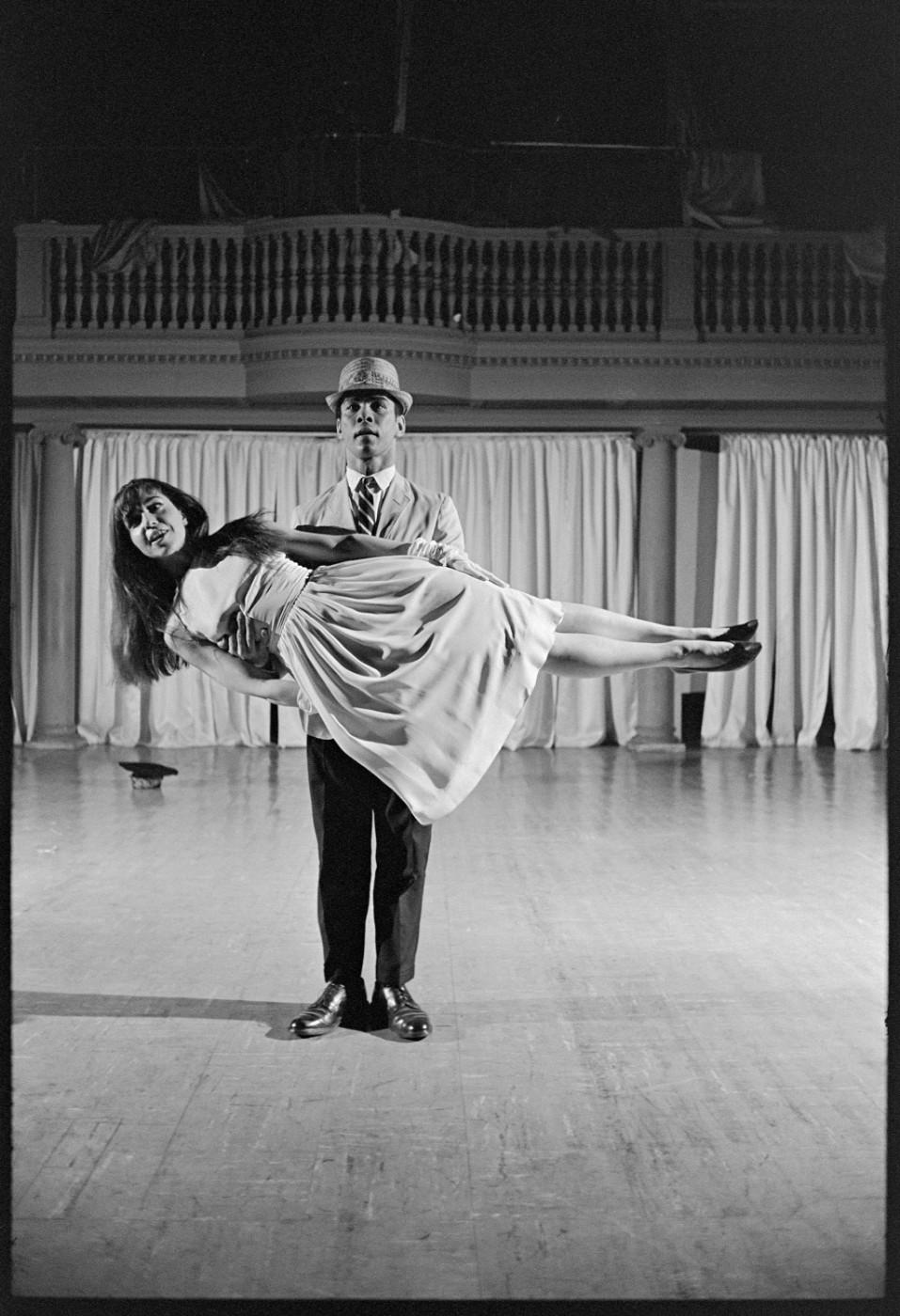

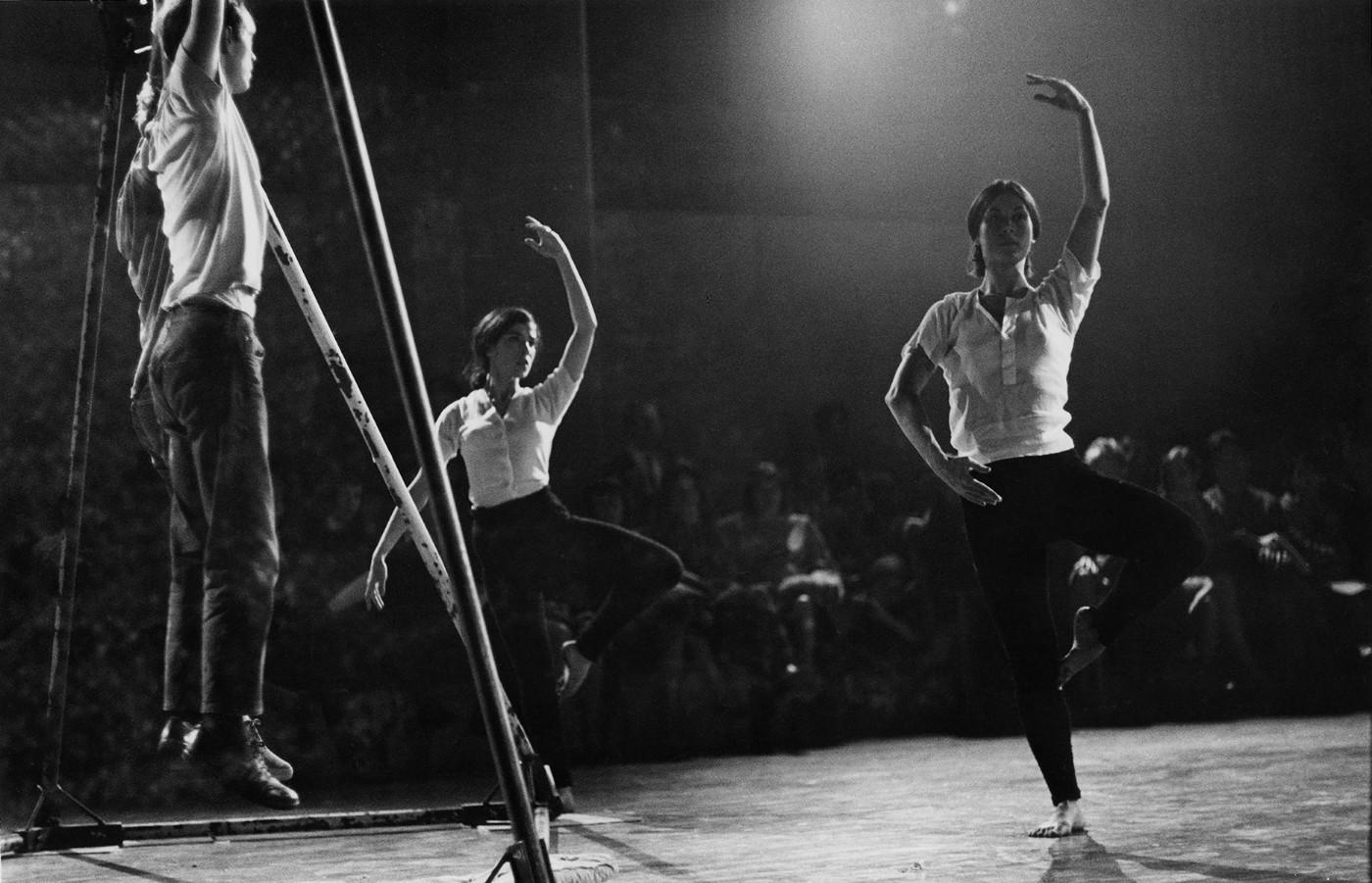

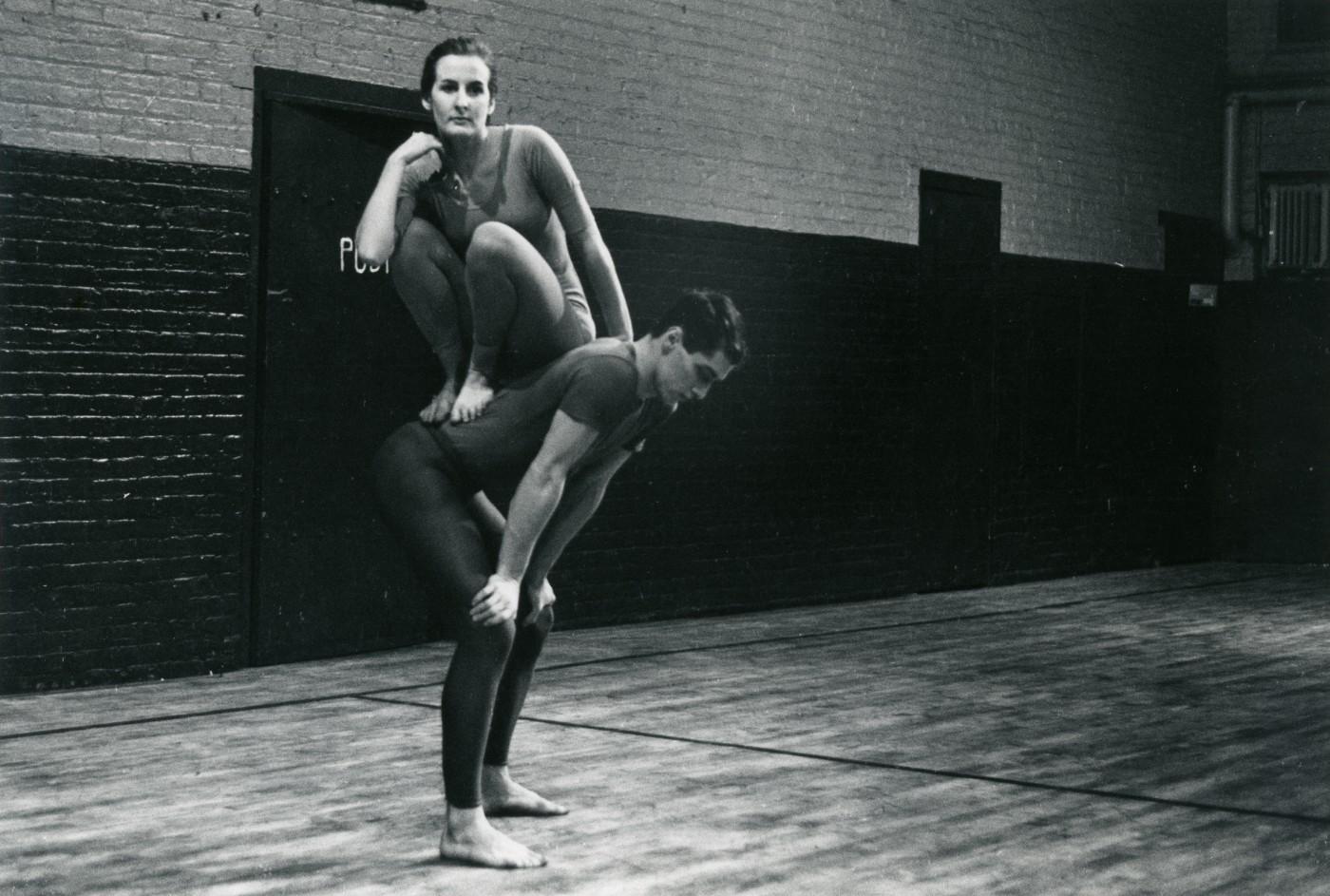

Taking its name from the Judson Memorial Church, a socially engaged Protestant congregation in New York’s Greenwich Village, Judson Dance Theater was organized in 1962 as a series of open workshops from which its participants developed performances. Redefining the kinds of movement that could count as dance, the Judson artists would go on to profoundly shape all fields of art in the second half of the 20th century. Together, these artists—including Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Philip Corner, Bill Dixon, Judith Dunn, David Gordon, Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Fred Herko, Robert Morris, Steve Paxton, Rudy Perez, Yvonne Rainer, Robert Rauschenberg, Carolee Schneemann, and Elaine Summers, among others—challenged traditional understandings of choreography. They employed unconventional composition methods to strip dance of its theatrical conventions, incorporating “ordinary" and more spontaneous movements into their work, along with games, simple tasks, and social dances.

“This exhibition emphasizes the cross-disciplinary activities and experimental spirit of Judson Dance Theater and New York’s Downtown scene in the 1960s," said Ana Janevski. "That spirit is especially resonant today, as the Museum has made a demonstrated effort to work cross- 2 departmentally and to highlight the central role played by dance and performance in the visual arts throughout the 20th century.”

Titled after a phrase used by choreographer Steve Paxton, The Work Is Never Done reflects both the Judson group’s spirit of experimentation and the ongoing importance of their work today. The exhibition attempts to account for the way the history of live work is mediated by the passage of time through retrospection, archival material, and oral history, including excerpts from interviews with Al Carmines, Steve Paxton, and Carolee Schneemann from the Bennington College Judson Project (1980–82). “Through our exhibitions, acquisitions, and live programs, the Department of Media and Performance Art is committed to considering how history is felt, sensed, and perceived, so as to place the past within its larger social context both then and now,” said Thomas J. Lax. The Work Is Never Done is organized into five galleries: the performance program in the Marron Atrium; 3 Dances: What Is a Dance?; Workshops; Downtown: Sites of Collaboration; and Sanctuary: Judson Dance Theater.

The Donald B. and Catherine C. Marron Atrium

The program in the Marron Atrium is organized into multiple-week increments, each of which features the work of one artist: Yvonne Rainer, Deborah Hay, David Gordon, Lucinda Childs, Steve Paxton, and Trisha Brown, as well as classes and events by Movement Research. In addition to live performances, a video compilation designed by artist Charles Atlas highlights historical material related to the respective featured artists. Editing material from both Judson and the post-Judson era, Atlas includes both individual and group pieces, emphasizing the relationship of the soloist to the ensemble and picturing how Judson Dance Theater influenced the future careers of this group of artists. For the weeks dedicated to Trisha Brown, Atlas has collaborated with Trisha Brown Dance Company’s former archivist, Cori Olinghouse, to create an installation that highlights Brown’s trajectory from Judson’s time to her later works. In the final weeks of the exhibition, the Museum will host Movement Research, a dance platform with a direct lineage to Judson, which will organize classes and workshops in the Marron Atrium