“We are pleased to be able to preserve and share these important drawings, which document numerous projects and reflect Michael Graves’s manifold interests and talents, here at the Museum, where he was known as family, and with our global audiences,” said James Steward, Nancy A. Nasher–David J. Haemisegger, Class of 1976, director.

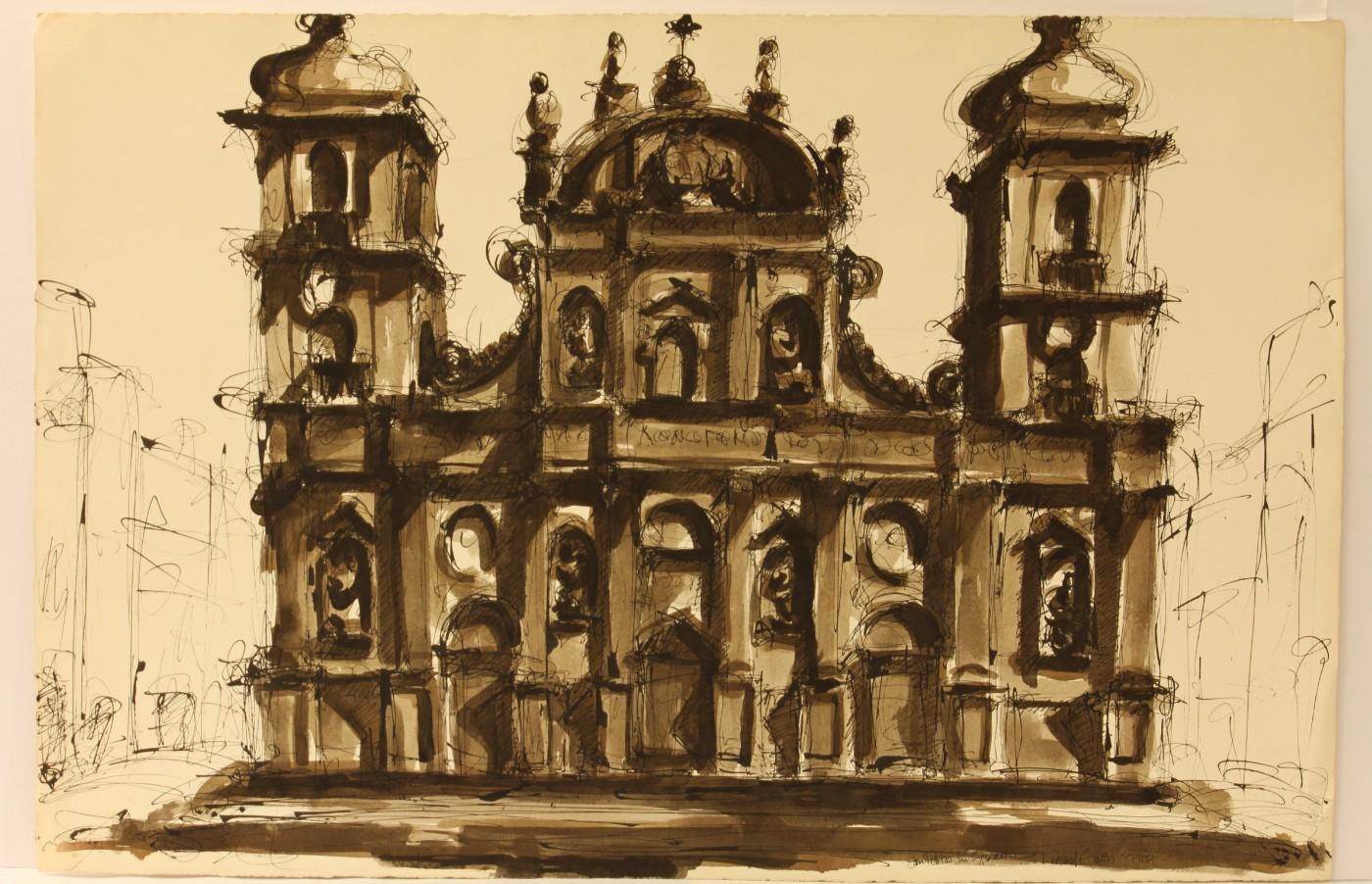

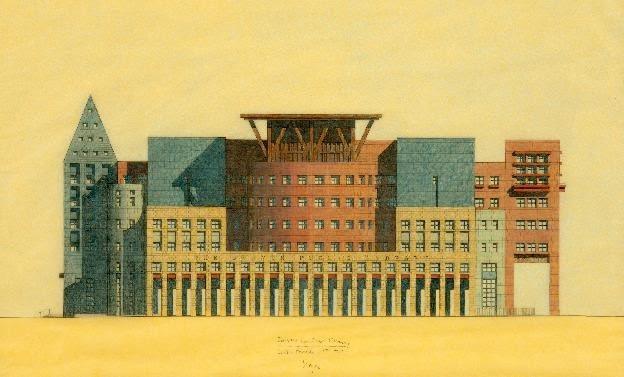

All of the drawings that will come to Princeton – which were variously executed in pen and ink, charcoal, graphite, colored pencil, watercolor and pastel – are in Graves’s own hand. There are exuberant drawings of historic monuments from his 1960s fellowship at the American Academy in Rome, pencil and ink referential drawings in sketchbooks, quick iterative design studies on yellow tracing paper, and meticulously colored building elevations. Together, the drawings in the collection form the essential visual archive of Graves’s work, revealing both his classical training and his commitment to draftsmanship – something Graves advocated for strongly in his teaching.

“As a prolific artist, architect and practitioner, Michael Graves considered drawing to be the foundation of his creative output,” said Sylvia Lavin, professor, history and theory of architecture at Princeton University and a leading scholar of Graves’s work. “This corpus of work that will now reside at the Museum will facilitate rich research and teaching opportunities around Graves’s enormously robust legacy.”

Graves is known worldwide for his innovative and transformative postmodern design of a vast range of large-scale architectural projects, interiors, consumer products (including his famous Alessi “whistling bird” kettle) and master plans for a global array of public and private clients. Graves also left his creative mark on Princeton, including at the Paul Robeson Center for the Arts on the corner of Witherspoon Street, completed in 2008, and at his former residence, The Warehouse, described by Steward as “Michael’s Monticello, the ongoing focus and forum for his innovation.” Like many 20th-century architects who designed furniture and household objects as well as homes and other buildings, Graves believed that good design should find its way into everyday life and be available for consumers at all price levels.