Aerial view of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Skillfully designed by world-renowned architect Moshe Safdie, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art highlights the beauty of its art and surroundings, nestled in the foothills of the Ozark Mountains in Bentonville, Arkansas.

Founded by Walmart heiress, philanthropist, and arts patron Alice Walton, Crystal Bridges has become one of the top art museums in the United States, offering amazing views, a sculpture park with nature trails, and an art collection spanning five centuries— ranging from portraits and landscapes to abstraction and immersive installations.

With so much to see, we’ve narrowed it down for you. Here are the top 10 pieces viewers can’t miss at Crystal Bridges.

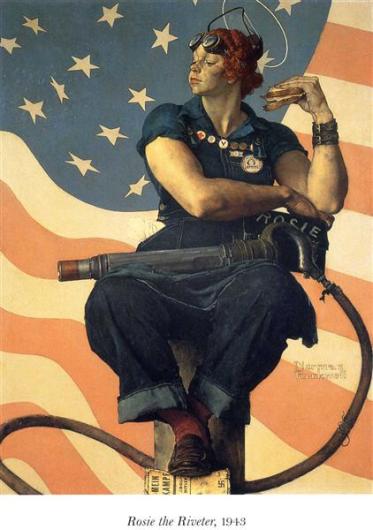

While the Early American Art Gallery is filled with figurative works by celebrated portrait artists and gorgeous landscapes by Hudson River School luminaries, the hands-down crowd favorite is Norman Rockwell’s (1894–1978) Rosie The Riveter (1943).

Famous for his cover illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post, painter and illustrator Rockwell’s version of the 1940’s pop culture symbol of patriotic courage, Rosie the Riveter has a mythic heroic quality.

Posed like a prophet in a Michelangelo fresco, Rockwell’s Rosie— a muscular, young, white woman in denim overalls— sits with a rivet gun in her lap. Flexing while eating a ham sandwich, her boot rests on a copy of Hitler’s manifesto, Mein Kampf.

Using hundreds of shoelaces donated by members of the public, artist Nari Ward (1963) spells out the first three words of the U.S. Constitution in massive cursive lettering. In 1787, when the Constitution boldly declared people’s right to govern themselves, the “people” it referred to were white male landowners and did not include women, African Americans, Native Americans, or other immigrants.

Through his choice of materials, Ward’s We The People evokes all of the people within America, making the term truly relevant.

Gabriel Dawe’s (1973) site-specific installation, Plexus no. 27, uses thread, painted wood, and hooks to create an ethereal exploration of light and color. Dawe uses his textile installations to emulate refracted light, materializing the ephemeral experience of a rainbow or ray of sunshine into a sculpture, giving light a form.

In 1954, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) designed the Bachman Wilson House in New Jersey. It was then transported to Crystal Bridges in January 2014 to protect it from recurrent flooding.

A beautiful example of Wright’s ongoing efforts to destroy the closed-in, boxy formality of 20th century architecture, the house is designed around an open floor plan, utilizing passive solar and radiant heat. That, combined with the tall windows and abundance of natural light, creates a calm, continuously flowing, low-cost living space.

American designer, inventor, and theorist R. Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983) imagined geodesic domes could be economical, efficient housing. The Fly’s Eye Dome is a lightweight fiberglass 50-foot prototype.

Constructed with circular openings called “oculi”— patterned like the lenses of a fly’s eye— for light and air flow, this fiberglass dome was first presented in the U.S. at the 1981 Los Angeles Bicentennial. Acquired by Crystal Bridges in 2016, the fully-restored geodesic dome is installed along their nature trails.

Robert Indiana’s (1928) corten steel LOVE sculpture stands at Crystal Bridges’ south entrance. One of over 50 versions of Indiana's Pop Art sculptures installed all over the world, its deep brown coloring harmonizes with the surrounding woodlands. The bold letters form a block— L and O sit on top of V and E, with the O tipped to one side, adding diagonal dynamism.

Another art trail installation and sculpture with versions around the world, Maman by Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) is a thirty-foot spider constructed of steel and brass, its egg sack filled with marble eggs. An homage to Bourgeois’ beloved mother— a clever textile artist who restored tapestries— the spider feels powerfully protective, rather than creepy.

An impressive steel tree-like sculpture installed at the museum entrance, Yield by Roxy Paine (1966) reaches curling silver branches towards the sky. Part of his Dendroid series, in which Paine combines welded pipes and rods with the visual language of trees to create something impossibly organic, Yield appears to have grown in some alternate reality where trees are made of metal.

Known for his work within the Light and Space movement— a California art movement merging minimalism with a focus on perceptual experiences of light and space— James Turrell (1943) has created a series of Skyspaces.

These freestanding concrete structures, artfully encrusted with stones, function as naked eye observatories, with an opening in the ceiling framing the sky and bench seating for visitors.

These installations often mix natural light with color, transforming viewers' experiences of the sky. The Way of Color at Crystal Bridges was the first Skyspace to feature LED lighting.

Another crowd favorite, the ebullient, bright red Two-Headed Figure Sculpture by Keith Haring (1958–1990) depicts a cartoonish humanoid form pushing up from the ground, fused at the waist to a joyfully barking dog. Two-Headed Figure Sculpture is currently on loan, but will return to the museum later this year.

Megan D Robinson

Megan D Robinson writes for Art & Object and the Iowa Source.