African American artists have contributed to this nation’s cultural landscape throughout its history. From colonial to modern times and realistic portraiture to minimalistic sculpture and striking abstractions, these diverse works and artists deserve more credit. Here we highlight twelve African American artists you should know more about.

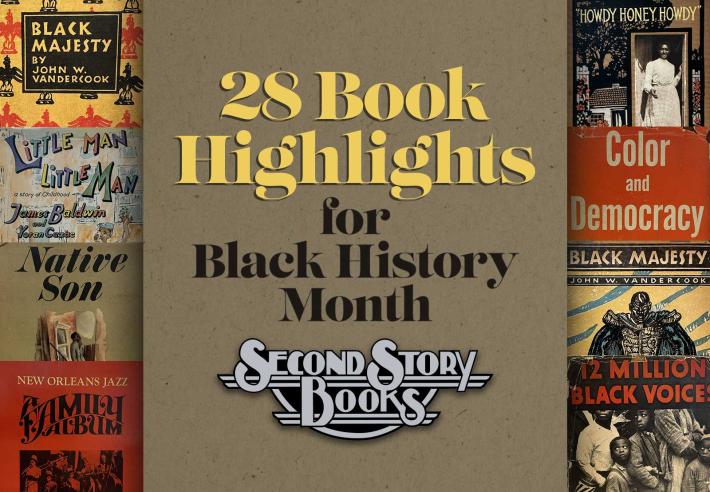

Grassy Melodic Chant, 1976. Acrylic on canvas.

An art teacher in Washington, D.C., for over thirty years, Alma Thomas (1891–1978) only began painting seriously after retirement. Initially a representative painter, her work evolved into exuberant abstract explorations of color and form, inspired by natural patterns. Her acrylic painting, Grassy Melodic Chant, bursts with light. Organic geometric blocks of turquoise color, arranged in mosaic patterns and bordered with white negative space, suggest the vibrant energy of blossoming flowers. Thomas was the first African-American woman to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in 1972, at the age of eighty-one. Her painting Resurrection was selected by the Obamas to be part of the White House art collection, the first work in the collection by an African American woman. In 2019, one of Thomas' paintings sold for $2.6 million at Christie's.

Walking, 1958. Oil on canvas.

Active in the Harlem Renaissance, artist, painter, sculptor, illustrator, muralist, and teacher Charles Henry Alston (1907–1977) was the first African-American supervisor for the Works Progress Administration's (WPA) Federal Art Project. His murals grace the Harlem Hospital and Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company. His dynamic 1958 oil painting Walking was inspired by the Montgomery bus boycott and the under-acknowledged women behind it. An abstracted group of women in brightly colored dresses move forward in a wedge formation, centered around a mother and child. Their angular shapes convey a sense of purposeful motion, capturing the urgent, hopeful impetus of the civil rights movement. In 1990, a bust of Martin Luther King Jr. created by Alston became the first image of an African American to be displayed at the White House.

28 Highlights for Black History Month 2023

Young Queen of Ethiopia, 1956. Limestone on wood base.

Celebrated painter and sculptor James Washington, Jr. (1908–2000) was born and raised in Gloster, Mississippi. Though he had trouble showing his art in segregated Mississippi, as an assistant art instructor for the Works Progress Administration, Washington was able to create a WPA-sponsored exhibition of Black artists, the first in the state. His job eventually moved Washington and his family to the Seattle area, where his art garnered increasing attention. Deeply philosophical, Washington sought to imbue his art with a universal spirit that could transcend race, class, and language. His limestone sculpture, Young Queen of Ethiopia has a regal dignity and striking beauty. Washington's home and studio are official historic landmarks in Seattle.

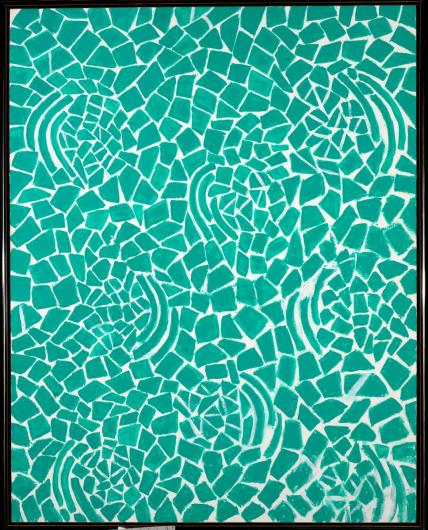

Crystalline Fantasy, 1998. Cotton and nylon with metallic and various threads.

Gwendolyn Ann Magee (1943–2011) started quilting classes in 1989 to make quilts for her college-bound daughters. Magee excelled at fiber art, creating both strong abstract pieces and narrative explorations of Black history, culture, and experience. Her past as a civil rights activist and career in social sciences infused her work. In Crystalline Fantasy, sinuous leaf and branch shapes seem to dance, their bright greens and blues popping against a yellow-orange background. Textures, striped patterns and dots swirl through the foliage, evoking traditional African textiles such as kente cloth. A graduate of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, her works are in the permanent collections of institutions across the United States.

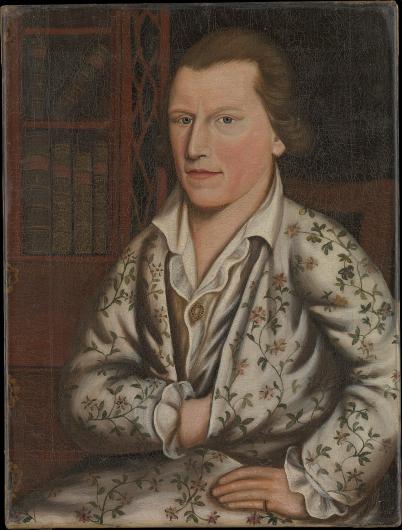

Portrait of William Duguid, 1773. Oil on canvas.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Prince Demah (c. 1745–1778) is the only formerly enslaved colonial artist with surviving work. Demah studied briefly with English portraitist and history painter Robert Edge, who was impressed with Demah’s painterly genius. He gained his freedom in 1775 when his owners fled back to England due to rising anti-Loyalist sentiment. In 1777, Demah enlisted in the Massachusetts Militia, but died the following year, probably of smallpox. Demah’s 1773 oil portrait of William Duguid, a Boston-based Scottish-American textile importer, skillfully conveys the silken sheen of Duguid’s floral dressing gown, the fine texture of his hair and the personality expressed in his steady gaze. The cause of Demah's death is uncertain, though some believe he died of smallpox.

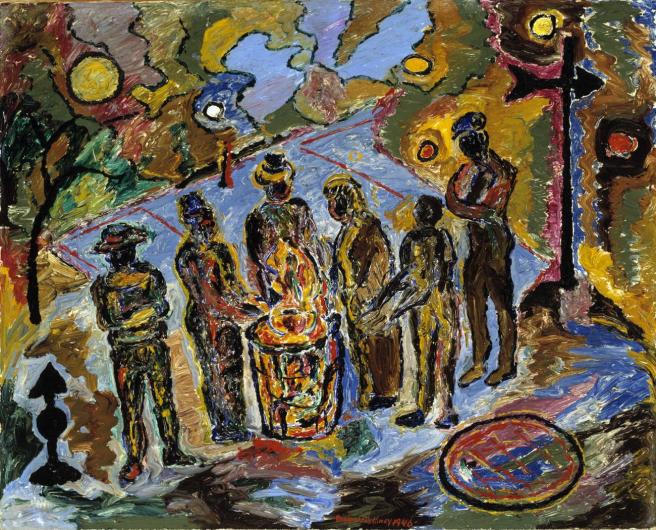

Can Fire in the Park, 1946. Oil on canvas.

American modernist painter Beauford Delaney (1901–1979) was a prominent figure in the Harlem Renaissance, widely recognized for his pastel portraits of notable African Americans such as WEB DuBois and Duke Ellington. After moving to Paris in the 1950s, he became interested in abstract expressionism and was influenced by Van Gogh’s painterly techniques and Fauvism’s radical use of color. Can Fire in the Park is a moody, atmospheric street scene. Six men huddle stoically around a fire in a trash can, which sits midway between a basketball court and a manhole cover in the street, in a scene reminiscent of the Great Depression. The men are all dark silhouettes, orange firelight reflecting on their clothes, with added light from a full moon and a globe streetlight. The landscape is fluid and dreamlike, its unlikely colors echoing the colors and shapes of the flames.

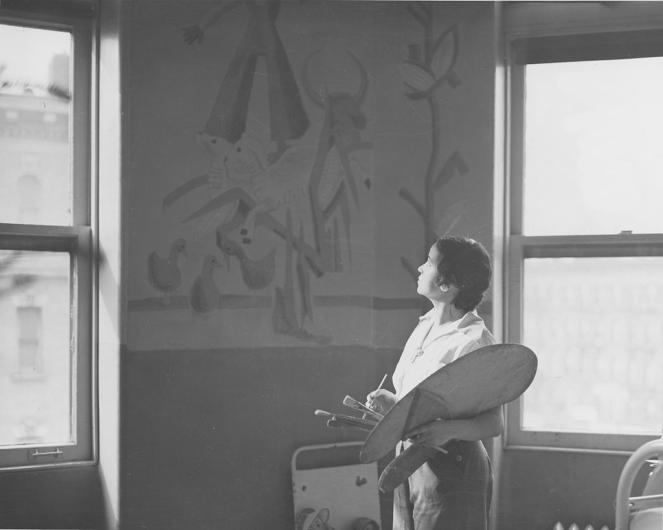

The artist works on her Mother Goose Rhymes mural, Harlem Hospital, 1938.

Elba Lightfoot (b. 1910) is known for her work on the Harlem Hospital WPA murals, which featured charming illustrations of Mother Goose rhymes. In 1935, with Charles Alston, Augusta Savage, and bibliophile Arthur Schomburg, Lightfoot founded the Harlem Artists' Guild (1935–41), an organization created to encourage young talent, foster art education, advocate for African-American artists, and work towards racial equality in WPA art programs in New York. The organization was instrumental in creating the Harlem Community Art Center.

Portrait of a Woman, 1920. Oil on canvas.

Portrait artist Edwin Harleston (1882–1931) participated in the Charleston Renaissance, an artistic and cultural boom between World Wars I and II. Harleston was committed to bringing dignity to the portrayal of African Americans, and his work served as an antidote to the stereotypical and caricatured depictions at the time. He married photographer Elise Forrest in 1920, and they set up the first African American studio and art gallery in Charleston, South Carolina. Harleston was active in local civil rights groups and became president of Charleston's newly formed branch of the NAACP in 1917. He won a number of awards for his work, but racial prejudice and segregation severely limited his success.

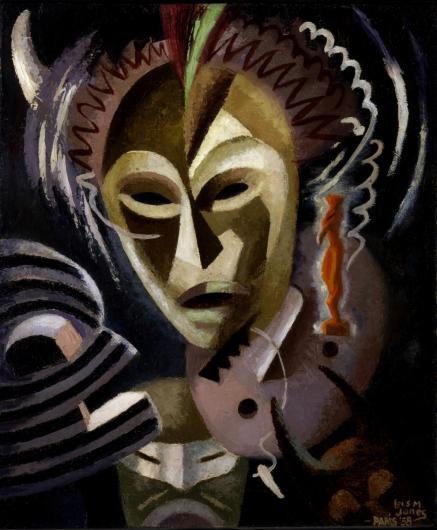

Les Fétiches, 1938. Oil on linen.

Loïs Mailou Jones (1905–1998) explored design, painting and illustration over her seven-decade career. Influenced by the Harlem Renaissance, the international art scene, and African and Caribbean culture, Jones’ style was constantly evolving. After getting her degrees in Boston, where she was unable to teach because of her race, Jones helped establish the art department at the Palmer Memorial Institute, a black preparatory school in Sedalia, North Carolina. Two years later, in 1930, she joined Howard University’s faculty. She was a teacher, mentor, and advocate for African-American artists. Les Fétiches is part of a series of oil paintings of African masks that she created while on sabbatical in France.

Fishbone tree, Bishopville, South Carolina.

Internationally recognized self-taught topiary artist and sculptor Pearl Fryar (1940–2020), started experimenting with topiary art in Bishopville, South Carolina, in 1988. Since then, his amazing garden, with approximately 150 topiaries, accented with found art metal sculptures, has become a destination. He was the subject of a critically acclaimed 2006 documentary, A Man Named Pearl, and visitors from around the globe continue to be attracted to his stunning abstract creations.

The Seine, c. 1902. Oil on canvas.

A student of Thomas Eakins at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937) spent much of his career in Paris, where Black artists had greater opportunities. He exhibited multiple paintings in the Paris salon, making him the first African-American painter to gain international acclaim and earning him patronage that allowed him to travel the world. Tanner used his travels as research for the popular biblical paintings he created, and to inform his Orientalist works. Before his death, the French state made him a knight of the Legion of Honour. Tanner's work is displayed in major art institutions around the world. One of his paintings, Sand Dunes at Sunset, Atlantic City, has been displayed in the White House's Green Room.

Land of the Lotus Eaters, 1861. Oil on canvas.

Part of the second generation of Hudson River School artists, Robert Seldon Duncanson (1821–1872) is best known for his sweeping landscapes of the American and Canadian wilds. A self-taught artist, as a young man Duncanson worked as an itinerant portrait painter and also painted small-scale, meticulous still lifes. Inspired by popular Hudson River School painters like Thomas Cole, Duncanson traveled the country taking in the scenery and preparing to paint it. At the onset of the Civil War, he moved to Canada and then England, where he his landscapes saw great success, before returning to America after the war. He is considered one of the only African American landscape painters of the nineteenth century, and was the most successful of them. Scholars continue to debate whether or not Duncanson incorporated racial metaphors in his works.

Megan D Robinson

Megan D Robinson writes for Art & Object and the Iowa Source.