Andrea del Verrocchio, Detail of David with the head of Goliath, c. 1466 - 69. Bronze. Bargello National Museum.

In the Old Testament, plenty of stories see the underdog as victorious against tyrannical powers. The city of Florence, an artistic powerhouse with relatively confined political power, saw figures such as David defeating Goliath and Judith slaying Holofernes as representative of the city’s ethos.

David, the Israelite shepherd and harpist who managed to hurl a stone in Goliath's head with a sling, became the favorite in Renaissance and Baroque arts. From Michelangelo's marble masterpiece to equally amazing but lesser-known works, here are some of the most fascinating representations of David from the period.

Donatello, David, 1440. Bronze. Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence, Italy.

Donatello's interpretation of David (1440) imagines the hero as an ephebic youth, aligning him with Athens. He is in the nude, except for a hat and boots, standing on top of Goliath's head and has a complacent, yet introspective expression. The bronze, with its smoothness, emphasizes his grace. This depiction marks the shift from seeing David traditionally as a prophet to a more heroic individual—a change especially evident in his triumphant pose.

Other nuances of his appearance can be traced back to the influence of Platonism in Renaissance-era Florence. Like Athens, David appears as one protected by celestial Eros against tyranny. Florence too was often envisioned as a mighty yet small power against tyrannical regimes. In addition, we can see that David's sword points to a decorative motif on Goliath's helmet, a triumph of Eros.

Donatello, David, 1408–1409. Marble. Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

Thirty years earlier, Donatello executed a marble version of David. Originally, the work was supposed to top one of the buttresses of Duomo di Firenze or the Florence Cathedral. In the end, it was ordered to be installed inside the Palazzo della Signoria. Stylistically, the statue straddles the line between International Gothic and Renaissance classic. While his stance hints at the Renaissance-era contrapposto, his elegance, coupled with his blank expression, is still deeply Gothic.

Andrea del Verrocchio, David with the head of Goliath, c. 1466 - 69. Bronze. Bargello National Museum.

Verrocchio's interpretation of David is in line with Donatello's, even though he traded Donatello's nudity for a courtier-like tunic. David is youthful yet triumphant and his avoidant gaze, coupled with the hint of a smile, conveys a demeanor of adolescent bravado. He wears a tunic adorned with ornamental bands which, coupled with the boots, partially conceals imitation-Arabic inscriptions.

This was done to convey a feeling of exoticism, a common strategy employed buy Italian makers throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Some scholarship believes that the model of this David's likeness is none other than Leonardo da Vinci, who was, indeed, one of Verrocchio's apprentices.

Michelangelo, David, 1501-04. Marble. Galleria dell'Accademia, Florence.

Made between 1501 and 1504, Michelangelo's David was originally supposed to be part of a series of prophets meant to adorn the eastern roof of the Florence Cathedral. Allegedly, Leonardo da Vinci was considered for this commission but the decision landed on Michelangelo, who chose to give his David a stance unlike the renditions by his predecessors.

Both Donatello and Verrocchio depicted David as triumphant, lording over a defeated Goliath. In contrast, Michelangelo's David is shown preparing for the battle. His arched brow, his tense neck muscles, and his bulging veins denote his eagerness. His heroic nudity was not immediately accepted: Instead, it was concealed by a garland made of twenty-eight gilded leaves.

Despite this, Michelangelo would continue to insist on nudity, both in his Risen Christ and in several characters in his Last Judgment. According to the apostle Paul, nudity denotes a naked soul. This, in itself, is indicative of sanctity.

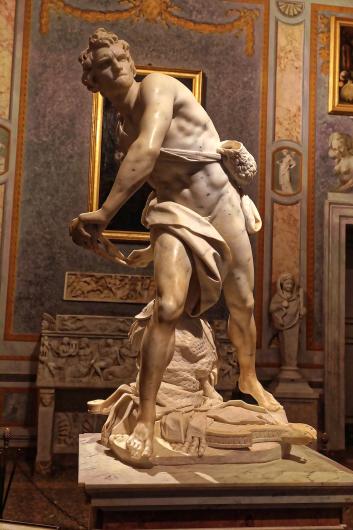

Gian Lorenzo Bernini, David, c. 1624. Marble. Galleria Borghese, Rome.

Bernini’s David is the product of a commission from his long-time patron Scipione Borghese, who already had several active commissions with the artist at the time. In fact, the artist momentarily abandoned his famed Apollo and Daphne, in which the nymph is rendered in the midst of her gradual morph into a laurel tree, to execute the new commission.

Unlike its predecessors, this David is here shown mid-action, in a markedly contorted pose that fully conveys the dynamism of the scene. Bernini additionally designed the statue to be stunning if observed from different points of view, thus making it an active component of room decoration. Wearing shepherd's clothes, David is shown frowning, biting his lower lip, in an expression that heavily contrasts with Donatello's and Verrocchio's coy youth. And, of course, Bernini’s reference to the Borghese Gladiator and The Discobolus by Myron is easy to detect in David’s readiness to attack among other details.

Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath, c. 1601. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

Several versions of Caravaggio's David and Goliath are known to the public. One from 1601, currently housed at the Museo del Prado, depicts David cutting off the giant’s tresses to reveal his head. The episode has no iconographic precedent.

Caravaggio’s Vienna David is notably less dark in mood. He is depicted as a more resolute character, if not downright triumphant. One hand carries Goliath's head, the other rests his sword across his shoulders.

Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath, 1610. Galleria Borghese, Rome.

Lastly, his Galleria Borghese David shows the young man with "an expression mingling sadness and compassion," wrote Christina Puglisi in the volume Caravaggio. His pensive expression also appears to some as languid, a reading that could be corroborated by the identity of the model—one of Caravaggio's own assistants, also known as the boy ‘who lay with him,’ while Caravaggio himself served as a model for Goliath's likeness.

Angelica Frey

Angelica Frey is a writer and translator living in Brooklyn. She writes about art, culture, and food.