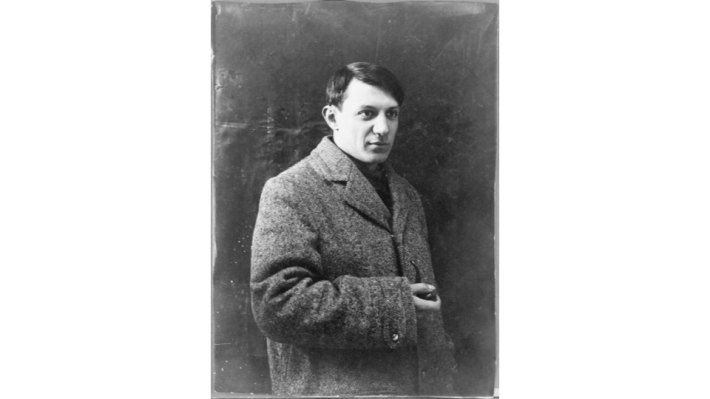

Dorothea Lange, Children of Oklahoma drought refugee in migratory camp in California, 1936.

Artists are tricksters, inventors, conjurers. They constantly engineer new ways to see the world, whether it be in fluorescently-hued watercolors, paintings that simultaneously depict an object from multiple angles, buildings that construct walls from glass and not brick, or photographs that make the ordinary appear extraordinary.

And so, it is fitting that when it comes to their own names, many artists mold new identities that defy tradition. Below are eight artists spanning two centuries, who bent rules when branding themselves. They adopted their mother’s family names instead of abiding by the traditional patriarchy, and often made the change at a point when they were making breakthroughs in the studio.

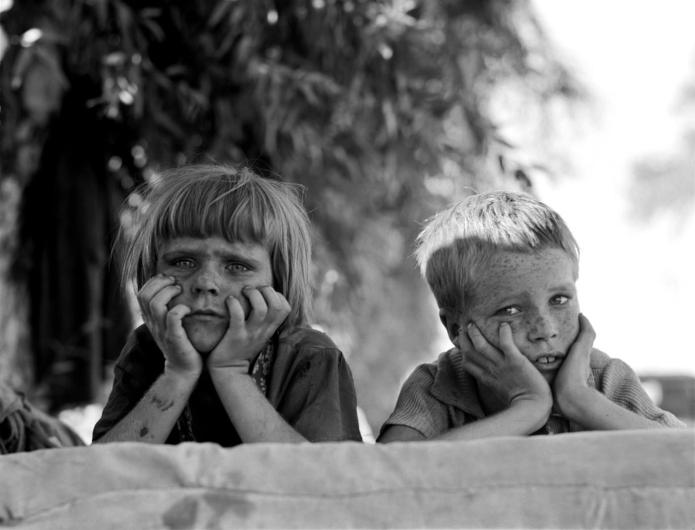

Portrait photograph of Pablo Picasso, 1908.

Pablo Picasso was convinced that a name with a double "s" was a surefire way for an artist to get people's attention. "Have you noticed," he asked photographer Brassaï in 1943, "the double s in the names of Matisse, Poussin, and Le Douanier Rousseau?" The only problem: He wasn't given a surname with a double s at birth. So, he changed it.

Whether or not he was being facetious with the reason he gave Brassaï, Picasso did choose to sign his mother's maiden name to his canvases instead of his given name, Pablo Ruiz. "My friends back in Barcelona called me by that name, [Picasso]," the painter explained. "It was stranger, more resonant than 'Ruiz.' And those are probably the reasons I adopted it."

Hercules Brabazon Brabazon, Venice from the Bacino. Watercolor. 9 x 15 inches.

The father of nineteenth-century English painter Hercules Brabazon Sharpe made a few failed attempts to persuade his art-loving son to study law, including cutting him off financially. These efforts were to no avail, and when Sharpe’s uncle (on his mother’s side) died, an opportunity for financial independence presented itself.

His uncle’s will stipulated that the benefactor would need to change his last name to Brabazon (the maiden name of the artist’s mother) in order to inherit the estate. The choice was a simple one for Hercules Brabazon Brabazon, as he was known as of 1847. Brabazon’s inheritance freed him to pursue a life of travel and painting, producing colorful watercolors that were praised by John Singer Sargent and are now in the collections of the Tate, British Museum, and Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Farnsworth House, 1945-1951.

Modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe famously said “less is more,” eschewing any excess ornamentation in his sleek designs that pioneered the use of streamlined steel and glass. It is a little ironic, then, that when it came to his own surname, he purposefully quadrupled it. The designer, born as Ludwig Mies, added his mother’s maiden name, Rohe, at an early stage in his career when he wanted to distance himself from his background as a stonemason’s son and identify as a sophisticated Berlin architect.

It was around this time, in 1921, that he also submitted a seminal design for a glass skyscraper to an architectural competition—the type of building for which Mies van der Rohe was ultimately known. Some have ventured a guess that the architect also wanted an upgrade from the literal meaning of his original last name; in German, mies means lousy.

Dorothea Lange, Children of Oklahoma drought refugee in migratory camp in California, November 1936.

Documentary photographer Dorothea Lange was born in New Jersey as Dorothea Margaret Nutzhorn, but lost allegiance to her father’s surname when he abandoned the family. Lange was twelve years old at the time and felt that his desertion was a defining moment of her childhood.

Roughly a decade later, Lange and a friend moved across the country to San Francisco in search of adventure and a fresh start. The photographer legally dropped her father’s name, and instead adopted the maiden name of her mother—Lange. Dorothea Lange was how she introduced herself when she opened her first photography studio in 1919, before her lengthy career documenting victims of the Great Depression, Japanese Americans interred during WWII, and the Jim Crow South.

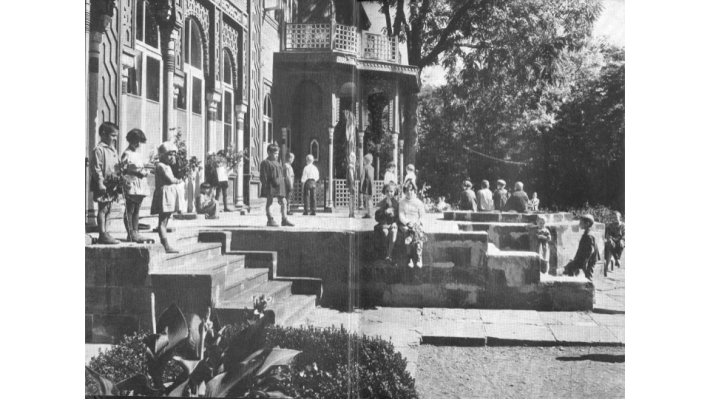

Margaret Bourke-White, Children at a rest home in Georgia, before 1923.

When American photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White divorced her college sweetheart—around the time that she was beginning her illustrious photography career—she saw it as an opportunity. “On a rainy Saturday morning I slipped down to the courthouse, quietly got my divorce, and resumed my maiden name… Bourke had been my mother’s choice for my middle name, and she always like me to use it in full,” Bourke-White wrote in her autobiography, Portrait of Myself (1963). “I had come out whole and happy with the knowledge of my new strength, and nothing would ever seem hard to me again.”

With her newfound fortitude, Bourke-White was the first female American war photojournalist, taking some of the earliest photographs of German concentration camps at the end of WWII; among her many international assignments, she took the last photographs of Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi.

Michael Ayrton, Icarus, 1973.

Of the many Greek mythological themes that British multimedia artist Michael Ayrton returned to repeatedly was Icarus, the son of master craftsman Daedalus who flew too close to the sun with waxen wings and fell from the sky. It is tempting to imagine that this thematic obsession was somehow related to the artist’s decision to change his last name to that of his mother, politician, and suffragist Barbara Ayrton, after the death of his own father, poet, and critic Gerald Gould.

Ayrton was active as a painter, sculptor, writer, novelist, and stage designer, soaring to experiment with multiple forms of art-making. “I like to take a larger risk,” Ayrton admitted, in an Icarus-like fashion, “and probably have a larger likelihood of failure on that account.”

Richard Serra, Sight Point (for Leo Castelli), 1975. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.

It was the Italian Fascist government that made the decision to change Leo Krausz’s surname in 1934, to that of his Italian-born mother (instead of his foreign, Hungarian father). This was an early sign of the wartime racism in Europe that ultimately led the renamed Leo Castelli to settle in New York, where he eventually converted the fourth floor of his Manhattan townhouse into an avant-garde gallery promoting contemporary American painters.

As an early supporter of Pop Art, Castelli gave artists such as Jasper Johns, Frank Stella, and Roy Lichtenstein their first solo exhibitions, and was among the first American art dealers to give monthly stipends to artists so that they could focus on making art.

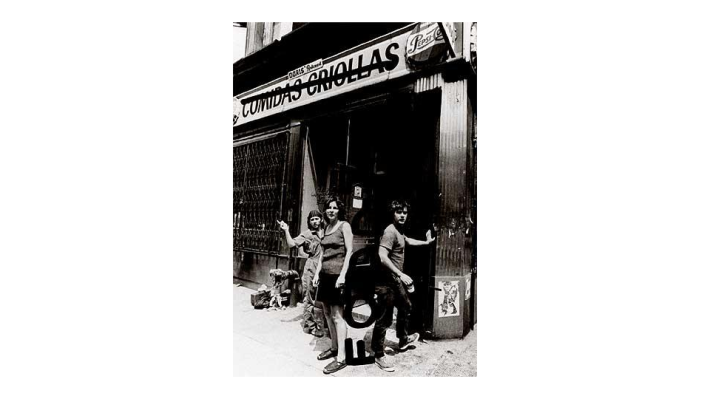

(Left to Right) Tina Girouard, Carol Goodden, and Gordon Matta-Clark in front of the closed-down bodega that would become their restaurant FOOD, New York 1971.

By the time Gordon Matta—one of Chilean Surrealist Roberto Matta’s six children—began his artistic career in the early 1970s, the art world already had a famous Matta. That might have been one reason why he chose to add the maiden name of his mother, artist Anne Clark, to his moniker at that point in his life.

Identifying as Matta-Clark distinguished him from his father, and also paid homage to the parent who actually raised him; Matta left Gordon’s mother four months after his birth. The year Matta-Clark changed his name was also the year that he opened FOOD in New York’s SoHo neighborhood—a restaurant managed by artists that was also a venue for performance artists and contemporary dancers.

Karen Chernick

Karen Chernick is an arts and culture journalist who loves a good story.