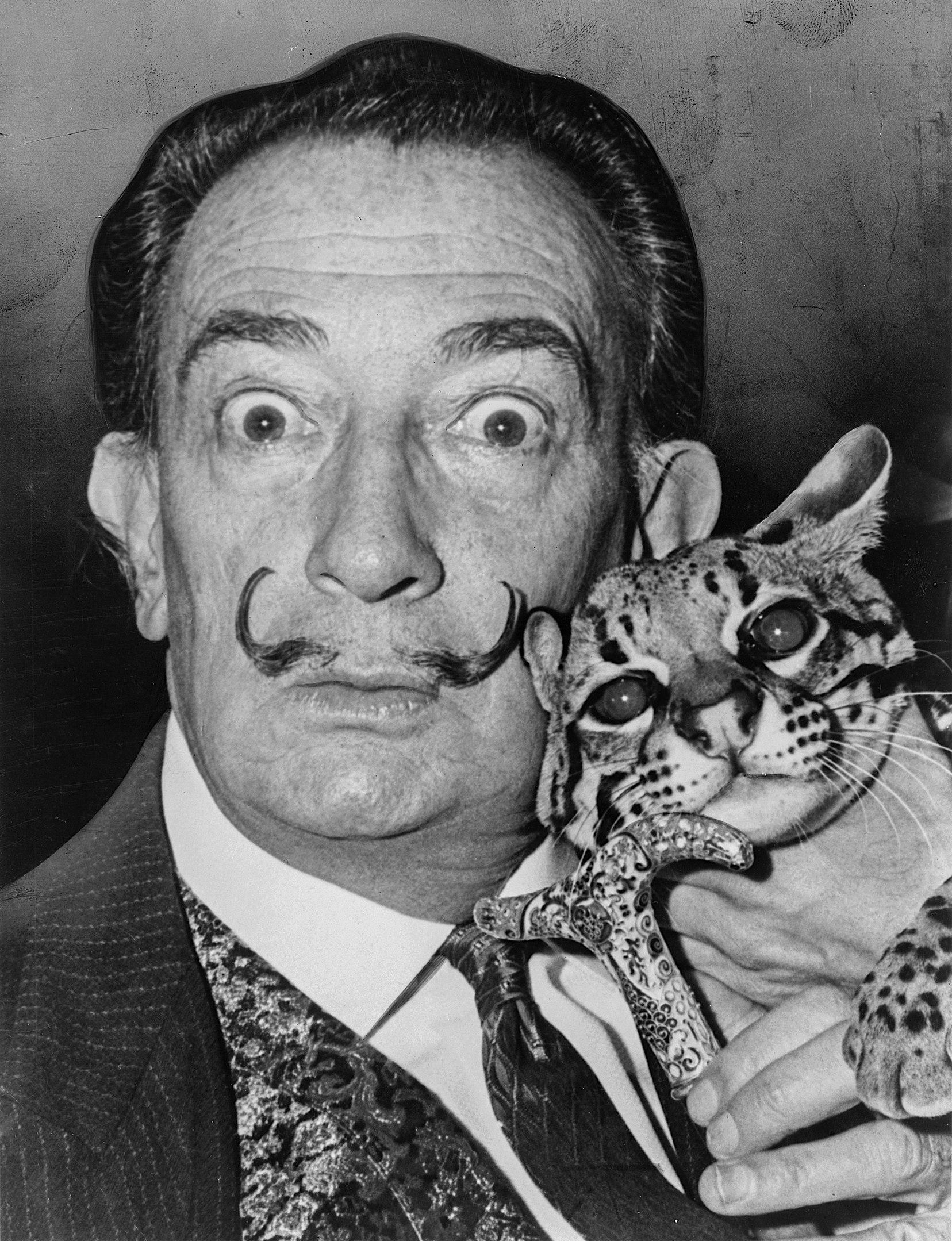

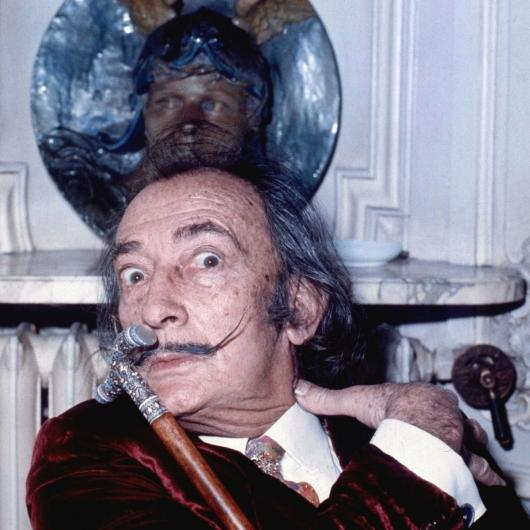

Salvador Dalí holding his pet ocelot, Babou

Surrealist artist Salvador Dalí may be best known for the dream-like paintings he created throughout his life, but the man was just as strange as his work.

Here are eight bizarre facts about the artist.

The Dalí family in 1910, with a young Salvador fourth from the left

Dalí was born just nine months after his older brother died of gastroenteritis at just twenty-two months old. When the artist was five, his parents took him to the grave of his older brother and told him that they believed he was his brother's reincarnation. They had even given him his brother’s name—Salvador.

Throughout his life, Dalí reflected on his relationship with his brother, even saying once, "[We] resembled each other like two drops of water, but we had different reflections." He "was probably a first version of myself, but conceived too much in the absolute."

He explored this concept of double identity in Portrait of My Dead Brother in 1963, which features an image of a young man—meant to be his brother—created from cherries. The artist described the work for an exhibition: “The Vulture, according to the Egyptians and Freud, represents my mother’s portrait. The cherries represent the molecules, the dark cherries create the visage of my dead brother, the sun-lighted cherries create the image of Salvador living thus repeating the great myth of the Dioscures Castor and Pollux.”

Exterior view of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando.

Though Salvador Dalí proved to be an exceptionally gifted artist, he wasn’t always a gifted student. He was expelled from the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in 1923 for participating in a student protest when painter Daniel Vázquez Díaz was passed over for a professorship. When he returned later to the same school, he was expelled again in 1926 because he said the professors who were slated to give him his final oral examinations were incompetent.

He even wrote later in his autobiography, “I am infinitely more intelligent than these three professors, and I therefore refuse to be examined by them. I know this subject much too well.”

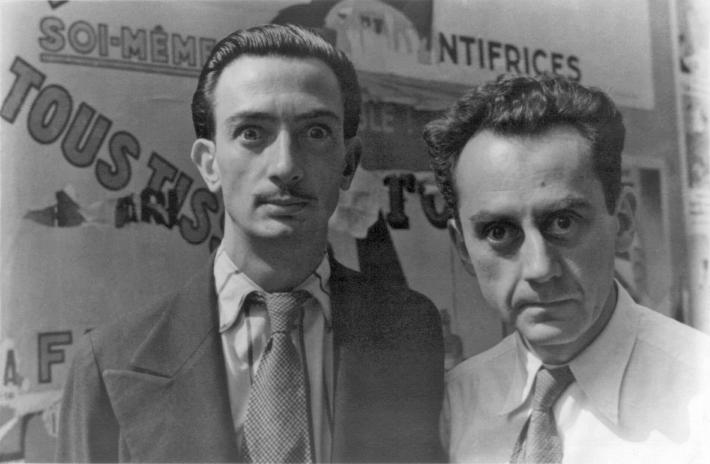

Man Ray and Salvador Dalí in 1934

Viewers of Dalí’s paintings will not be surprised to learn he was a fan of Sigmund Freud’s work on the subconscious. Dalí read the famed psychoanalyst's book, The Interpretation of Dreams while in art school and was inspired to use the concept of self-interpretation in his own creative work.

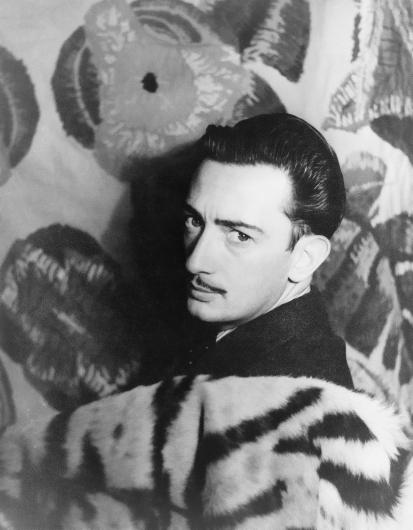

Salvador Dalí in 1939

In 1938, Dalí was able to meet Freud in London, where he showed the psychoanalyst an article he wrote on paranoia and his painting, Metamorphosis of Narcissus (1937), the first work he created entirely from his “paranoiac-critical method.”

Though Freud had not been a fan of Surrealism, Freud wrote after the visit that the artist was an “undoubtedly perfect technical master.”

Portrait of Salvador Dalí by Allan Warren, 1972

Though hallucinations are often linked to psychedelics, Dalí didn’t use drugs. Instead, he developed a method of accessing his subconscious, which he called the “Paranoiac-Critical” method. In order to create a dreamlike state, he would sometimes stare at objects until they appeared to transform into other forms, bringing on hallucinations that influenced his art.

Portrait of Francisco Franco

While many of the other artists in the Surrealist movement self-identified as Marxists, Dalí harbored a passion for dictators. Not only did he depict Vladimir Lenin in The Enigma of William Tell (1933) and refuse to denounce Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, who he met several times, but he also had a sexual fascination with Hitler that led André Breton to order Dalí’s removal from the Surrealist movement.

Breton wrote, “Dalí having been found guilty on several occasions of counterrevolutionary actions involving the glorification of Hitlerian fascism, the undersigned propose that he be excluded from surrealism as a fascist element and combated by all available means.”

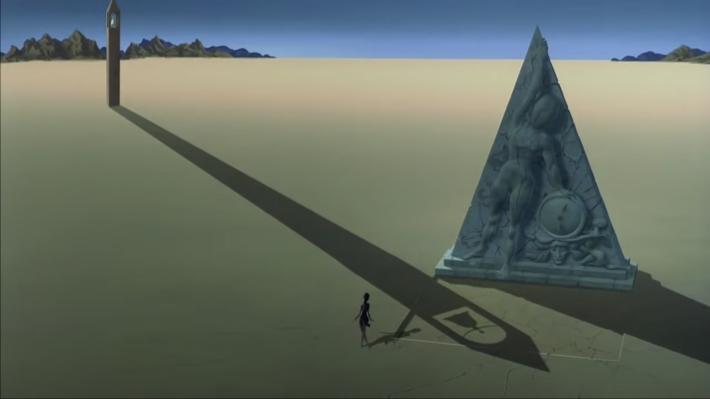

Still from Destino

Famed director Alfred Hitchcock asked Dalí to help create paintings for the dream sequences in his 1945 film, Spellbound, which starred Gregory Peck and Ingrid Bergman. The paintings were also included in the plot as clues to one of the characters’ psychological problems.

The artist also worked with John Hench, a Disney designer in 1946 on an animated movie called Destino. For the film, Dalí completed twenty-two oil paintings and drawings, which became storyboards. Though the film was unfinished due to budgetary constraints, it was later released as a six-minute short in 2003.

Still from a Dalí Chocolate Commercial

Though many artists look down on commercial work, Dali was not one of them. Throughout his long career, the artist created magazine covers for Vogue and Town and Country, the logo for Chupa Chups lollipops, and ads for major brands, such as De Beers, S.C. Johnson & Company, Gap, and Datsun. He even worked as a spokesperson for companies like Alka-Seltzer and Lanvin, a French chocolate company.

André Breton mocked the artist for his commercial work, calling him “Avida Dollars,” which meant “eager for dollars."

Peggy Carouthers

Peggy Carouthers is a writer, editor, and custom content manager based in California. She enjoys creative writing and learning about art and literature. She is passionate about connecting companies with audiences.