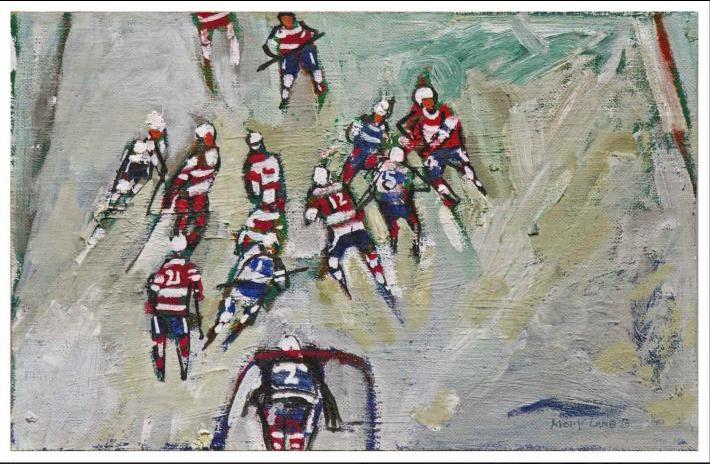

Molly Lamb Bobak, La partie de hockey.

Modern hockey’s rules developed gradually over the course of the twentieth century, but iterations of the game extend back thousands of years. Today, hockey inspires a great deal of passion in its players and fans, who often see it as central to their sense of local, regional, and national identity.

Hockey lends itself quite naturally to artistic engagement and has been a topic of a number of exhibitions throughout the US and Canada over the past decade. Some artists draw attention to those who continue to be left out of the sport, some poke fun at the seriousness with which fans approach it, and others ask difficult questions about hockey’s relation to individual health and national image. Hockey is inarguably a violent game, one that periodically provokes violent spectator responses. But it is a community rallying point that can still foster a sense of belonging in players and fans. These nine works of art ask us to think more critically about what the sport is and its cultural and material legacy in the twenty-first century.

James Duncan, Canadian Watercolour, skating on St. Lawrence River, mid-19th Century.

Prolific Irish painter and lithographer James Duncan produced images of outdoor leisure in pristine, often wintry landscapes after immigrating to Montreal in 1830. In this watercolor, Duncan does not present an organized game, but rather dozens of anonymous figures gliding across a natural ice rink. Some fall, and others balance on sticks, congregating in small groups or moving independently. But the icy landscape of what was then called Lower Canada is the focal point of the painting; skaters are accessories and compositional balancing devices that enhance the crisp blue of the sky, ice, and water beyond. Duncan’s work is an homage to a particular place and time when the seeds of what would become hockey were being planted.

Molly Lamb Bobak, La partie de hockey

As the first official Canadian war artist of WWII, Molly Lamb Bobak was a groundbreaking Canadian painter. Throughout her decades-long career, she maintained a self-professed fascination with chaotic, large community gatherings. She loved being caught up in a crowd, and hockey matches were an ideal avenue in which she could become subsumed in the energy of a local event. Here, even without visible spectators, she uses bright colors and rough brushstrokes to push her players around the ice, forcing them to negotiate negative space. Her mark-making itself invokes the electricity of a live match. Bobak’s many studies and paintings of local hockey games swirl with energy and reflect her signature method of conveying multisensory barrages of color, motion, and noise, all tempered by a nuanced understanding of compositional balance.

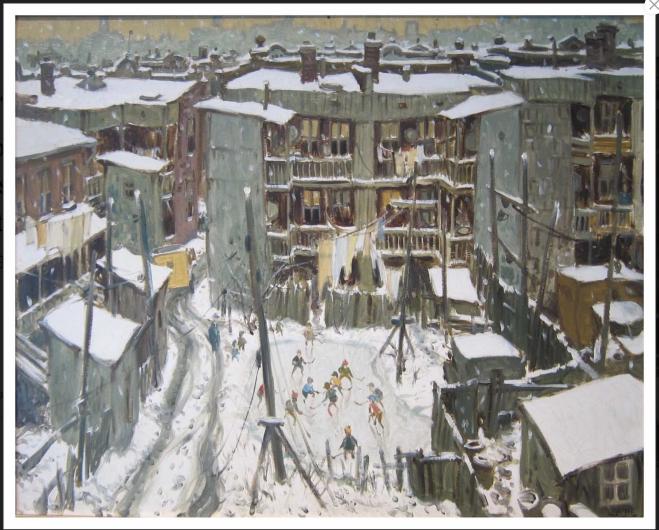

John Little, Faubourg à m’lasse, Dorion Street, 1965.

In Canadian artist John Little’s painting, children play hockey on a makeshift ice rink amid tenement houses, gray fences, and leaning electrical poles. Little offers a scene that is at once a portrait of a quotidian urban pastime and an homage to a doomed working-class neighborhood in inner-city Montreal.

The painting’s name references the area’s nickname—the “molasses neighborhood,” which was partially evicted and razed in the 1960s to make room for shiny new city infrastructure. Here, thick snow and ill-fated buildings seem to dwarf the game and its players. And yet, this is a scene of vitality and youth, with hockey grounding the lively community. Today, the painting is part of famed former NHL player Vincent Damphousse’s private collection.

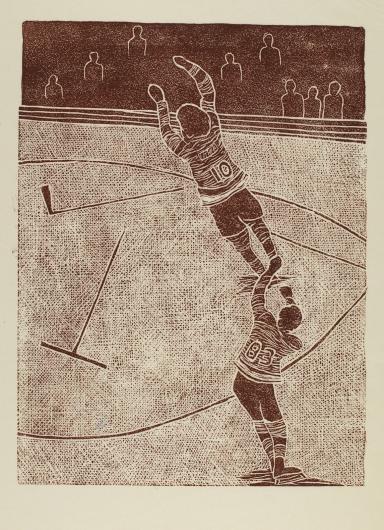

Frank McClure, Hockey Players, 1979.

In Frank McClure’s Hockey Players, produced during the last year of the American artist and scientist’s life, two players face a ghostly mass of spectators while appearing to soar above the ice. Number 83 tumbles upward from the bottom right of the composition into Number 10’s ankles, setting off a cascade of spatially ambiguous motion. The print’s rough lines and meticulous cross-hatching make up a scene of violence that is anonymous and fluid, straightforward yet dancelike.

In addition to being a prolific printmaker, McClure worked as a biochemist and conducted pivotal early research into how fluoride could prevent tooth decay. His works of art examine scenes of everyday American life such as landscapes, flora and fauna, table settings, and agriculture. They reflect a scientist’s careful, almost systematic exploration of texture, value, and negative space.

Charles Pachter, Hockey Knights in Canada, 1986. Mural on southbound platform of College St. Station, Toronto.

As the home of Toronto’s hockey team from 1931 until 1999, Maple Leaf Gardens was a cultural pilgrimage site of sorts for NHL fans. On both platforms of the city’s College Street subway station, just meters away from the arena, is Charles Pachter’s hockey-themed mural. Pachter rendered players in two 35-foot-long panels on opposite sides of the train platforms: the Maple Leafs on the southbound and the Montreal Canadiens on the northbound. This is a fitting arrangement considering the intense rivalry between the two teams. The murals are striking, with each player pared down to shades of red, blue, and white. Pachter presents the athletes in tense close-ups, with lines and shapes reminiscent of pop art, their arrangement and scale engulf underground travelers.

James Carl, Pain, 1995-6.

For Pain, a title that is French for “Bread” and cleverly calls to mind the inevitable results of contact sports, James Carl sculpted two life-sized goalie pads out of dough. Like much of the artist’s body of work, made of quotidian and playful materials, this piece is uncanny and humorously similar to actual pieces of protective equipment.

Both bread and padding have a hard shell covering a soft interior. Carl’s work also evokes the organic and delicate nature of the human body, where actual padding needs to be durable enough to protect its vulnerable wearer. Here, handmade bread forces viewers to consider the perishability, familiarity, and imperfection of flesh, and the consumable nature of athletes in the public eye.

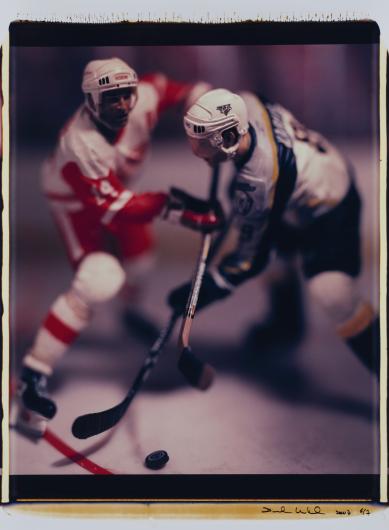

David Levinthal, Untitled from the series Hockey, 2007.

American artist David Levinthal is known for the photographs he takes of tableaux made of toy figurines. His series are all deeply rooted in mid- and late-twentieth century American cultural phenomena—Hockey is no exception. Here, two opposing toy players are locked in, their bodies captured in the split-second before collision. The dramatic contrasts in focus push the lifelike players’ helmets toward the viewer while pulling their torsos into the background. The result is a disorienting scene that mimics how we might encounter a fast-paced game in real-time. The format of Levinthal’s piece recalls a hockey card, but the tight composition and very shallow depth of field immerse viewers more than any playing card ever could.

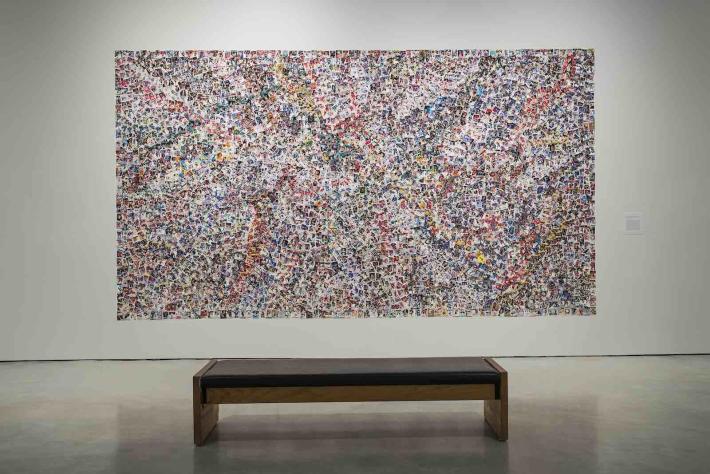

Marc-Antoine K. Phaneuf, Canadian Painting, 2013-2019.

Multidisciplinary Québecois artist Phaneuf’s large canvas is literally made of popular culture ephemera. His Canadian Painting consists of thousands of hockey cards, some of them decades old, arranged in a composition reminiscent of Canada’s most famous Abstract Expressionist, Jean-Paul Riopelle. The cards are layered thickly, revealing countless examples of the visuals now long associated with hockey: melodramatic action shots, hopelessly-dated hairstyles, and beer sponsor logos. Viewers need to spend time with Phaneuf’s work to unpack its many components. It is equal parts poignant and funny, elevating the consumerism and hyper-masculinity associated with hockey to mythic levels while revealing the absurdity of our collective reverence for the industry.

Hazel Meyer, Container Technologies, 2019.

For Container Technologies, artist Hazel Meyer collaborated with the Canadian AIDS Society—which has, for many years, been storing the AIDS Memorial Quilt in hockey bags donated by Molson Brewery. The quilt itself is a crucial means of reckoning with Canada’s AIDS epidemic: over 600 panels each represent a Canadian who, since the 1980s, has died from complications related to the illness and many of whom were members of the LGBTQ+ community. For their installation, Meyer displays the twenty-two hockey bags containing quilts. Many layers of fabric, each with their different cultural associations and histories, combine to form more than the sum of their parts. The bags literally hide their contents, much like professional sports have long resisted or tried to mask queer inclusion and diverse identities.

Rachel Ozerkevich

Rachel Ozerkevich holds a PhD in Art History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She's an art historian, writer, educator, and researcher currently based in eastern Washington State. Her areas of expertise lie in early illustrated magazines, sports subjects, interdisciplinary arts practices, contemporary indigenous art, and European and Canadian modernism.