Albrect Dürer, Detail of Self-portrait, 1498. Oil on panel. Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) is one of the most important artists in art history. He has even been called "the Da Vinci of the North." Though this label is somewhat dismissive of his individual talent—and Dürer would not have enjoyed being referred to as such—it can help indicate just how impactful the artist was in his own right, particularly to those who may not know much about him.

An incredible artist and businessman, he fortunately lived and worked just as Gutenberg’s printing press (c. 1440) and movable type (c. 1450) began to take off. Dürer exhibited great artistic skill at a young age and developed a keen interest in prints early on. He was able to channel both into a thriving artistic career, producing fine art for wealthy patrons and printed work that was able to, for the first time, be disseminated to the masses.

Albrecht Dürer, Self-portrait at the Age of 13, 1484. Silverpoint. Albertina, Vienna.

This self-portrait was created when the artist was just thirteen years old. A child prodigy of sorts, Dürer’s intrinsic artistic abilities became apparent at a rather young age. Although the artist initially apprenticed with his goldsmith father, as was the custom, he pivoted a mere two years after this self-portrait was made to focus on art with a position under painter and printmaker Micheal Wolgemut. This apprenticeship ended in 1490.

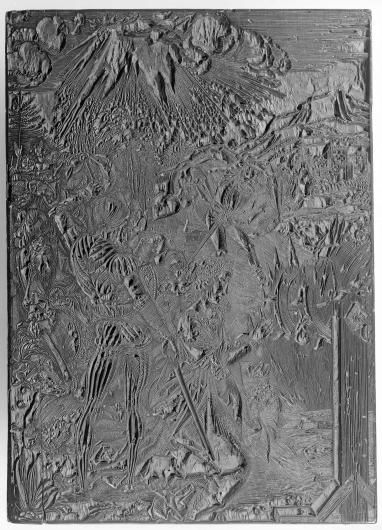

Albrecht Dürer, woodblock for The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine, c. 1498. Black ink on carved pearwood. 5 1/2 × 11 1/8 × 1 in. (39.4 × 28.3 × 2.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

Dürer went on to study under several artists who were practiced in painting and printmaking. Today, he is the primary painter-printmaker of the art historical record. In the late 1490s, Dürer produced a great number of unusually detailed woodcut prints which brought him financial success. The artist appears to have quickly developed a keen eye for powerful imagery.

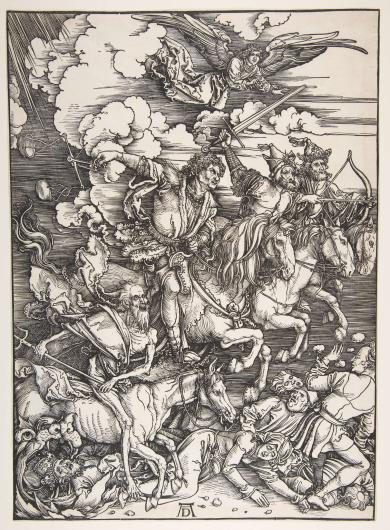

Albrecht Dürer, The Four Horsemen, from Apocalypse, 1498. Woodcut. 15 1/4 x 11 7/16 in. (38.8 x 29.1 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

In 1498, Dürer published Apocalypse with Pictures (or Apocalipsis cum figuris). The first book ever to be conceived, designed, and published by an artist, this publication comprised of fifteen prints that illustrated scenes from the biblical Book of Revelations. Dürer’s technical proficiency was such in these images that he managed to blur the lines between the engraving and the woodcut. Curving and thin yet dynamic and strong—modern historians and printers alike continue to marvel at his ability to design for a block of wood.

Albrecht Dürer, Sketches of Animals and Landscapes, 1521, Pen and black ink, and blue, gray, and rose wash on paper. 10 7/16 x 15 5/8 in. (26.5 x 39.7 cm). The Clark Art Institute.

Dürer’s extensive diaries and carefully preserved correspondences—throughout which he would often sketch—reveal much about the artist. He was deeply thoughtful and business-oriented. He showed a keen awareness of his audiences’ taste, an interest in the impact of his artwork, and he ruminated constantly over the monetary side of his art-making.

Jobst Harrich, Copy of Dürer’s Heller Altarpiece (the original was destroyed in a fire), ca. 1614–17. 74.4 x 54.3 in (189 cm x 138 cm. Historical Museum Frankfurt.

Dürer’s awareness of the financial-boon printmaking offered emerges particularly clearly in a letter to Jacob Heller, for whom the artist was in the midst of completing a rather involved altarpiece at the time this was penned. In the letter, Dürer openly laments that he would be wealthier, had he spent that time printmaking.

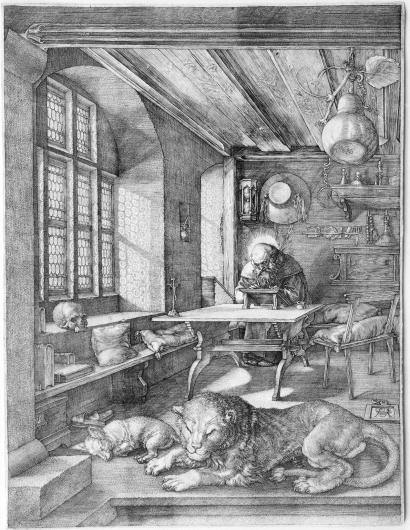

Albrecht Dürer, Saint Jerome in His Study, 1514. Engraving. 9 11/16 x 7 7/16 in. (24.6 x 18.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum, New York, NY.

This is one of Dürer’s three so-called master engravings of 1513-4 and is considered representative of the peak of sixteenth century burin technique. Saint Jerome—a scholar and theologian—was popular at the time of this print’s creation. Particularly inspiring to Humanists and Reformation leaders, the image sold well. The skill with which Dürer captures the nuances of Northern European painting—not to mention the effects of sunlight on stone, glass, and wood—with nothing more than lines and dots remains practically unmatched.

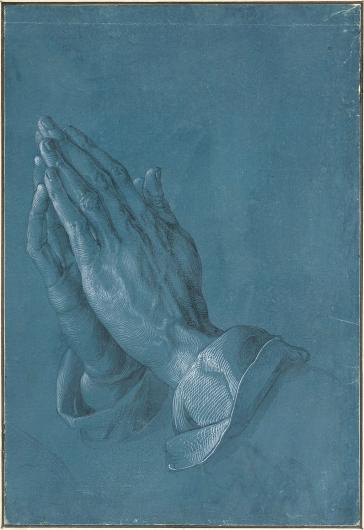

Albrecht Dürer, Praying Hands, c. 1508. Drawing. 11.5 in × 7.8 in (29.1 cm × 19.7 cm). Albertina, Vienna.

This drawing—a preparatory sketch for an altarpiece—has become one of the most reused visuals of all time. Incorporated into everything from tattoos to deeply-researched works of fine art to bumper stickers, the apparently unceasing lifespan of this casual artwork is a testament to Dürer’s ability to create powerful images.

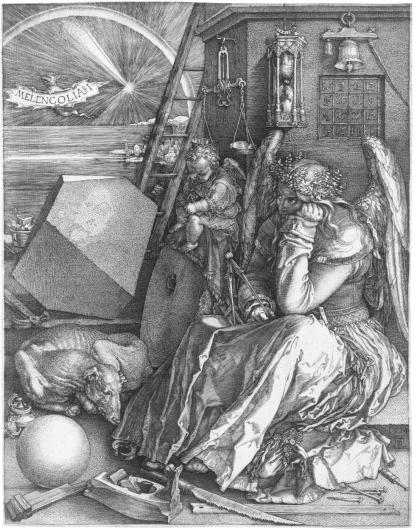

Albrecht Dürer, Melancholia 1, 1514. Engraving. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Dürer was deeply inspired by Italy and, in many ways, seemed to envy the import given to art and artists within the country. Certainly, he was entranced by the amount of knowledge and study happening there. He became one of the first Northern European artists to regularly use one-point perspective.

Albrect Dürer, Self-portrait, 1498. Oil on panel. Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain.

During his second trip across the Alps, Dürer wrote to Williams Pirckheimer, “Here I am a gentleman, at home a parasite.” Despite these lamentations, the heightened, Italian status of art and the artist made its way back to Germany via Dürer’s own work, if nothing else. In this late self-portrait, the artist has fashioned himself in order to highlight his greatness. He is luxuriously dressed, his expression is nearly haughty, and the three-quarter-length format emphasizes his face (identity) and his hands (connection to art).